April 24, 2019; The Root

Earlier this year, NPQ put its focus on the harmful legacy of racist, Depression-era federal housing policy that kept African American households from the benefits of real-estate-fueled wealth acquisition that allowed white Americans to move comfortably into the middle class and beyond. In a recent article in The Root, Michael Harriot highlighted that the lingering harm of these polices goes much deeper, broadening the great gap of black-white inequality we are still struggling to resolve in education, health care, and criminal justice.

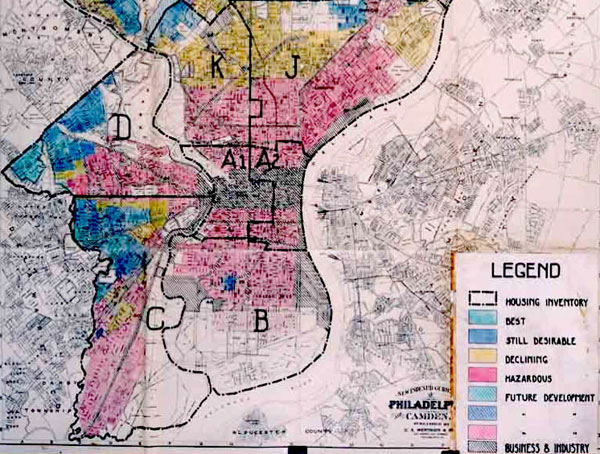

When the federal government created the Home Owners Loan Corporation in 1933, it “essentially prohibited government-insured lending to non-white neighborhoods (which were colored red on maps, leading to the term ‘redlining’).” Harriot points out the disparate impact of these maps; they built invisible walls around already segregated communities.

Because everyone was poor during the Great Depression, these maps did not reflect economic status. In fact, upscale black neighborhoods like LaVilla and Sugar Hill in Jacksonville, Fla., home to Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Zora Neale Hurston, were deemed “too risky,” by the HOLC. But instead of using these maps only for HOLC refinances, which would have been racist in and of itself, banks began using these maps for all home purchases and refinances. Again, with Jim Crow segregation in place, blacks couldn’t simply move to the non-redlined, white neighborhoods. So, because of this, as generations of Americans lifted themselves out of poverty, black people could not take part in the primary driver of wealth, homeownership.

Public schools rely heavily on local property taxes to balance their budgets. The legacy of redlining is felt by communities of color whose property values are significantly lower than neighboring communities just outside the “red line.”

“These lower home values,” Harriot says, “mean that schools in black neighborhoods receive less funding…according to a 2019 study by EdBuild, schools serving nonwhite students receive $23 billion less in funding than majority-white schools despite serving the same number of students. It’s why the average nonwhite school district receives $2,226 less per student than a white school district.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The dots connect: Children living in redlined communities, attending underfunded schools, are more likely to find themselves enmeshed in a legal system that differentially imprisons African Americans.

In Baltimore, maps of poverty, drug arrests and police shootings are nearly identical and are almost totally contained within the boundaries of formerly redlined areas. A study by the state of Maryland Public Defenders Office also found that 13 of the 15 zip codes where suspects routinely receive higher bail amounts were in redlined areas.

In attacking important social problems one by one, Harriot writes, we may be missing, perhaps intentionally, the elephant in the room: “Black people have been denied access to intergenerational wealth building by a government policy that is interwoven into the fabric of American society. This nation became an international economic superpower because it was built on the foundation of slavery.”

If the decision to exclude the black community from participating in the decades of wealth-building that built the white middle class was not just an administrative mistake but reflective of an ongoing policy of keeping African Americans unequal, must we not address that issue head-on and move the discussion of reparations to the center stage?

This will not be easy. Cyndi Suarez, writing in NPQ, recently cautioned that “the key challenge appears to be how to confront the enormous debt to black Americans while addressing the very real economic challenges other Americans are facing. (Not that these are mutually exclusive.)” We need to collectively grapple with the debts owed to the African American community apart from efforts to tackle the challenges of education, housing, medical care, environment, and criminal justice. We need to ask ourselves the same questions about bills unpaid to members of Native American nations and other communities that have been defaulted upon.

It may be easier to conclude, as Bernie Sanders has, there are better ways to address the crises facing the American people and our communities right now than “just writing out a check.” But to do so is to guarantee we will find ourselves reflecting on the next policy that duplicates the redlining experience, placing one more well-intentioned but biased action on top of the last.—Martin Levine