February 7, 2020; LitHub

Some nonprofits start out small, with budgets under $10,000 and a vision of growth. Others land on the scene with a splash—fully formed, well-funded, and ready to take on the world.

That’s how the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction plans to start its life. Founders announced that starting in 2022, the prize would award $150,000 CAN (about $113,000 USD) each year to a book by a woman or nonbinary writer.

“We wanted to go big on it so that people paid attention,” said Canadian novelist Susan Swan. Swan and Janice Zawerbny established the prize, along with an anonymous corporate donor.

The prize foundation has a healthy start, but they’re planning for stability; between now and 2022, says Swan, they’ll fundraise to cover administrative costs and look for their jury panel.

“We will try to make sure there is a solid diverse group of women serving as jurors and build a database to that effect,” she adds, citing correspondence with Roxane Gay as a starting point for considering diversity and equity in an intersectional way.

The prize’s deliberately splashy debut is meant to draw attention, not just to women and nonbinary writers but to the stories they tell. Carol Shields, the prize’s namesake and a Canadian novelist who died in 2003, wrote stories about middle-class housewives—a subject that often gets books classified as “chick lit,” or otherwise less substantive or significant. Why a book about self-exploration through relationships is considered less valuable or interesting than a book about self-exploration through wandering across the country is anyone’s guess.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

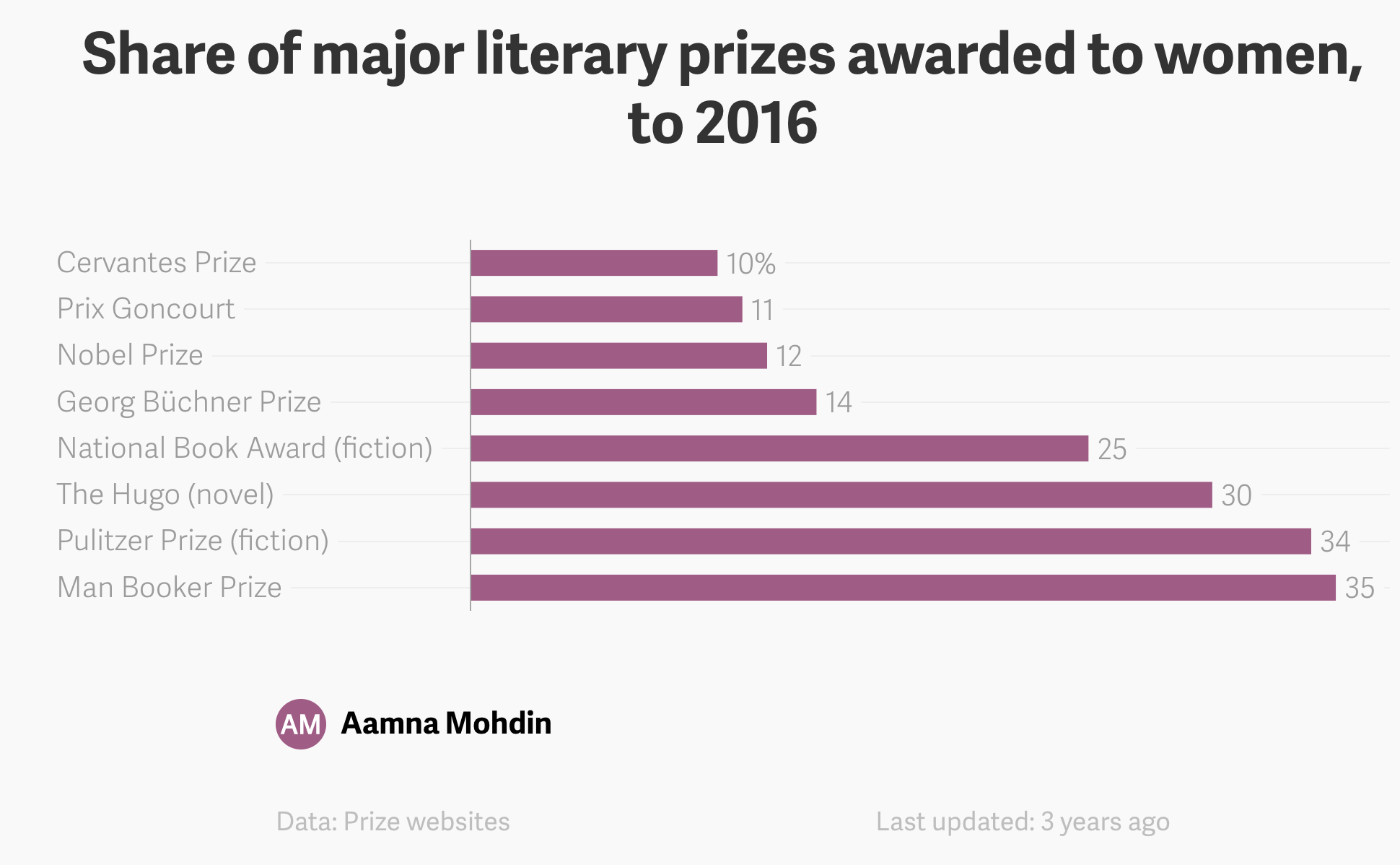

In 2016, Quartz looked at the demographics of literary prize winners from each prize’s founding up until that year.

Quartz found that no prize, even those founded more recently (whose percentages presumably don’t suffer from the decades prior to feminism’s second wave), reached parity. In fact, the Cervantes prize, founded in 1976, is the youngest one on that list and has the smallest ratio of female or nonbinary winners. The next youngest prize is the Booker, which was founded in 1969 and at 35 percent comes closest to male/female parity. The Booker prize has undergone some turmoil lately, having lost their longtime sponsor last year, but they pulled it together and awarded the 2019 prize jointly to Canadian Margaret Atwood and Anglo-Nigerian Bernardine Evaristo. Atwood and Evaristo are, respectively, the oldest and the first Black women ever to win.

The new Carol Shields prize has a bigger purse than every award on that list except the Nobel, and most other awards besides. Typical literary awards give around $10,000; the Nobel awards about $1.5 million and the Booker famously bumped its prize up to £50,000 in 2002. Mostly, though, awards recognize excellence but don’t subsidize a writing career.

Zawerbny says, “I see this prize primarily as having an economic function for women writers,” pointing out that prizes can exponentially boost book sales. She and Swan have been planning this launch since 2012.

The importance of this idea, that the prize would allow women and nonbinary recipients to support themselves as writers, comes directly from the experience of its namesake. The Globe and Mail’s Marsha Lederman writes, “Carol Shields earned Hanover College’s top writing prize when she graduated from the Indiana school in 1957. She did not, however, receive it. The committee gave the prize to the second-place student instead. Because he was a he. He would need to make a living, the thinking went, and the prize would help.”

The large prize doesn’t come without strings. There is, uniquely, a mentorship requirement. Winners are asked to work with another young writer not just on stories, but on winning fellowships to support themselves. The winner and their mentee will receive a residency at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Alberta, a partner in launching the prize.

Karen McBride, an Algonquin Anishinaabe writer from the Timiskaming First Nation and a mentee of Swan’s, said, “It gives a sense of hope, I think, for new writers, new women writers, to know that there’s [a prize] out there, specifically for them…to know that this exists and that there’s a mentorship involved, that someone will be there to help craft your work, it’s priceless.”—Erin Rubin