In the aftermath of the economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, economic recovery will hinge on how policymakers face two critical challenges: 1) improving the quality of jobs; and 2) ensuring that wages steadily rise for workers in the bottom half of the wage distribution. Meeting these twin imperatives will help ensure that economic growth and progress is broadly shared.

These objectives are not fanciful. For the first time in 50 years, from 2014 through 2019, New York City, where I live, saw strong, historic growth in wages and family incomes for workers who fell in the bottom half of the city’s income distribution, declining poverty, and flattening income inequality. Since such gains were not borne out nationally, New York City’s pre-pandemic experience merits a closer look.

New York City’s Pre-Pandemic Experience

In the immediate pre-pandemic years, new laws doubled the local minimum wage and established other wage standards. Combined with strong employment growth (full employment in 2018 and 2019), these changes fostered the strongest gains for the lowest-paid half of workers in New York City in at least half a century. After steadily rising for three decades (1980-2010), income inequality began to decline.

Can New York build on these gains? Might other cities follow its example? Perhaps New York City’s experience in the past decade was a blip, but if it wasn’t, the city offers a case study that makes it easier to imagine sustained national movement toward greater employee and wage equity.

Understanding the National Historical Pattern

The post-World War II era was marked by relatively broadly shared prosperity. Such prosperity, of course, should not be exaggerated, as many were excluded. Families of color and unmarried women did far less well than traditional white families and white men. Still, the postwar period saw, on balance, rising living standards and a gradual reduction of economic inequality across the country.

In the 1980s, that pattern changed dramatically. Thanks to neoliberal policies (lower tax rates on the wealthy, more corporate-friendly regulation, suppression of labor unions), economic gains began concentrating increasingly at in the top wealth bracket.

Initially, at least in New York City, real incomes for the middle class continued to rise. However, that changed in the 1990s as corporate downsizing took hold and the middle “hollowed out” with the rapid increase in low-wage jobs.

In the last decade, New York City deviated from the national pattern, and income inequality began to decline. How did this happen? City and state policies in the last decade more than doubled the state’s minimum wage … and other policies boosted pay for airport workers, app-dispatched drivers, and early childhood education teachers.

Workers of color felt the brunt of these changes; median family incomes for New York City’s Blacks, Latinxs, and Asians stagnated from the late 1980s to the early 2010s despite considerable economic growth and rapidly rising incomes at the top. While such stagnation was a national trend, the shift was especially dramatic in the Big Apple, where the share of total income going to the richest one percent rose from 12 percent in 1980 to 41 percent in 2012, a concentration twice the national average.

Can Local Policies Make a Difference? The New York City Story

National public and private policy choices, not inevitable economic forces, drove much of this polarization. Importantly, when it comes to confronting income inequality, local policies matter, particularly in a city as large as New York, which accounts for about five percent of the national economy.

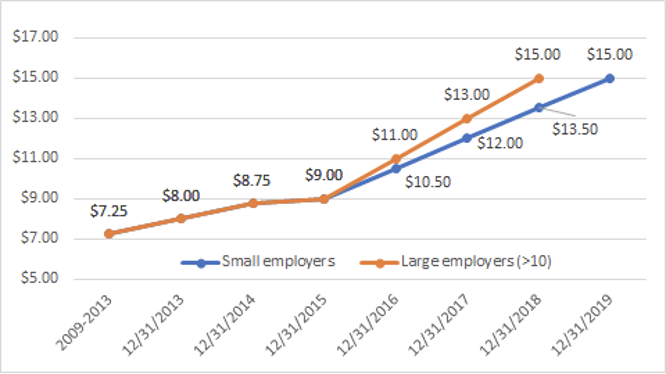

In the last decade, New York City deviated from the national pattern, and income inequality began to decline. How did this happen? City and state policies in the last decade more than doubled the city’s minimum wage, raising it from $7.25 in 2013 to $15 an hour by 2019. Other policies boosted pay for airport workers, app-dispatched drivers, and early childhood education teachers and mandated paid sick days and paid family leave. More details are provided by the graphs below.

New York City minimum wage levels more than doubled between 2013 and 2019

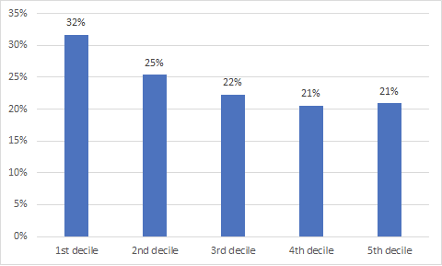

New York City’s pro-worker policies boosted pay for workers in the bottom half of income distribution and, together with historically low unemployment, enabled two million city workers and their families to collectively get a bigger slice of the city’s economic pie for the first time in half a century. Government economic data reveal that workers in the bottom half of income distribution received $5,000 (or 24 percent) more in inflation-adjusted wages in 2019 than in 2014. As the chart below shows, workers at the 10th percentile wage (10 percent of workers make less, 90 percent make more) saw a 32 percent increase in inflation-adjusted wages between 2014 and 2019, and there were increases of at least 20 percent for all other workers in the bottom half of wage earners up to the fifth decile.

Substantial inflation-adjusted 2014-19 wage change for NYC workers in the bottom half of wage earners

Source: New York City Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, New York City Government Poverty Measure 2019, December 2021.

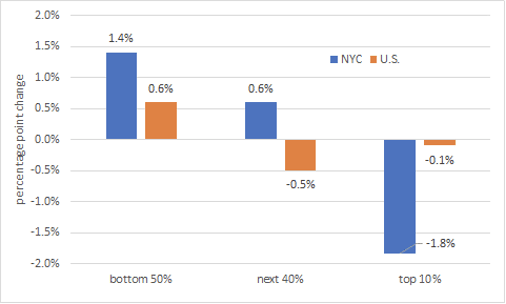

Higher wages for the lower half of earners were so significant that they translated into a higher share of total wages paid in New York City over that period, according to income tax data. Total wages going to the lower half of earners were $2.6 billion greater in 2019 than if their wage share had held constant. From 2014 to 2019, the share of total wages going to those in the bottom half of earners rose by 1.4 percentage points. This was much greater than the average 0.6 percentage point gain for those in the bottom half across the entire country. The increasing share for those at the bottom came at the expense of the richest 10 percent of New York City households whose share of total wages fell by 1.8 percent over this period. New York’s wage and pro-worker policies made the difference.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The share of total New York City wages going to households in the bottom half of the income distribution rose from 2014-19 while it fell for the top 10 percent

Source: CNYCA analysis of income tax data from the New York City Independent Budget Office and the Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income.

The rising wage share for households in the bottom half of earners helped lift such households’ income share as well, with a two-percentage-point increase, or about $5,000 per family. The income gain for those in the bottom half of the income distribution in New York City was far greater than the 0.2 percentage point increase nationally. The sharp income share increase for the bottom half in the city was accompanied by a 3.8 percentage point decline in the share of total incomes going to the richest 10 percent.

Income gains for those below the richest 10 percent also meant 20-percent-plus real median family income gains (averaging $11,500 per family) between 2010 and 2019 for the city’s non-white families. This is striking in contrast to the two previous decades of stagnant or declining real incomes. New York City’s poverty rate fell from 21 percent in 2010 to 17 percent in 2019 (its lowest level since the early 1970s). Child poverty dropped by a quarter, falling from 31 percent to 23 percent between 2010 and 2019, respectively (also the lowest level in nearly 50 years).

Despite Gains, Stark Inequality Persists

Still, at the beginning of 2020, shortly before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, stark income inequalities continued in New York City, and significant pay, health, and other disparities existed across racial and ethnic groups. Between one third and half of the city’s households of color had incomes that were insufficient to provide for basic family budget needs, and wealth inequality was more pronounced than income disparities. Indeed, despite wages and family incomes rising in the past decade, far too many New York City families still struggle to make ends meet.

It is probably no surprise that residents of New York City face a higher cost of living than the national average. New York adjusts for this and in 2019 set the poverty line for a family of four at $36,242. Occupational data from the New York State Department of Labor indicate that the median annual salary across all occupations in New York City ($58,260 in 2021 dollars) is only modestly higher than the poverty line and falls far short of family needs. Applying the University of Washington’s “Self-Sufficiency Standard” suggests that, depending on its size, a family must earn between $70,000 and $100,000 annually to truly meet household needs. Not surprisingly, a much higher percentage of households of color have inadequate incomes than white households. Forty-four and 50 percent of all Black and Latinx households, respectively, have earnings that fall short of meeting budget adequacy.

Pandemic Effects on Economic and Racial Inequality

In addition to causing the deaths of over 41,200 city residents (disproportionately affecting Black and Latinx households), the pandemic has had lopsided economic effects. While hundreds of thousands of low-paid workers and small-business owners in face-to-face service industries lost their livelihoods to protect public health, wages have risen for high-income earners, almost all of whom kept their jobs and benefits.

Whereas employment in the nation overall has recovered to its February 2020 pre-pandemic level, as of June 2022, New York City’s job count was still 200,000 (or 4.3 percent) short of the pre-pandemic level. This pandemic-driven jobs deficit is concentrated in the face-to-face industries where annual wages are a fraction of the pay received by workers in finance, tech, information, and professional services, many of whom continue to work remotely.

Wall Street and big tech companies and their workers have flourished. Workers without a four-year college degree suffered more than two-thirds of pandemic job losses. Workers ages 18-24 were disproportionately affected, and dislocated workers were much more likely to be workers of color. Essential workers in health and human services on the frontlines, sectors where Blacks are disproportionately represented, have seen their ranks thinned by job burnout, while workplace demands and health risks have mounted.

New York’s Twin Challenges Today: Supporting Quality Jobs and Pay

So, what must New York City do now? After past economic downturns, most recently after the Great Recession, a laissez-faire approach was adopted, keeping unemployment rates for workers of color high for several years. This time must be different.

Bringing down unemployment will be hard due to the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising interest rates in the hopes of reducing inflation. On the other hand, federal infrastructure and climate-change related investments should help bolster demand for blue collar jobs that reasonably compensate non-college educated young workers, provided that city and state governments help dislocated and young city residents obtain these jobs.

To ensure more broadly shared prosperity, efforts to raise pay and improve protections for low-wage workers should also be continued. This year’s city and state budgets raised pay modestly for home health care and nonprofit human services workers. Further increases are needed, and long undercompensated childcare providers should have their pay lifted. The state can also index its minimum wage for inflation, and catch-up adjustments are needed for recent losses due to inflation. Legal and enforcement changes are needed to address the plight of the 10 percent of workers who are misclassified as independent contractors—their pay is more than one-third below their counterparts who are wage workers, and they lack access to essential social insurance programs like unemployment insurance and paid family leave.

In one of his most progressive actions, Mayor Eric Adams substantially boosted the city’s earned income tax credit by $250 million, effectively raising the take-home pay of low-wage workers. The city could vastly improve the equity of its property tax system by enacting reforms recently proposed by a property tax reform commission—this would particularly help many home-owning, moderate-income families of color in the boroughs outside of Manhattan.

In short, the goal should be to substantially increase the number of New York self-sufficient families who can afford their family budget. The half-decade before 2020 indicates that such an increase is possible; it shows how city and state actions raised the wage floor, leading to rising employment for low-income workers and historic gains in income equality.

Principles for Addressing Income Inequality Beyond the Big Apple

Above, I outlined some steps New York City can take to replicate the gains in income equality of the past decade. What should other states and cities do? Every community is different, but a few principles stand out:

- Adjust the minimum wage locally to raise wages for the least well off and index minimum wages to inflation—and take other steps to improve the quality of low-wage jobs, for example by requiring paid sick leave and paid family leave.

- Target policies to support low-wage workers in sectors that are typically under compensated, particularly in “care industries” such as home health care and childcare and nonprofit government-funded human services.

- Ensure that federal infrastructure and climate dollars are directed to support job creation and higher wages in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

- Make local and state taxes more progressive through actions such as establishing or raising the amount provided by a state earned income tax credit program and/or establishing a child tax credit program.

- Take action to support gig workers by passing laws that curb the use of independent contractors in areas of the economy where workers are paid poorly and have little on-the-job autonomy—and by ensuring that these workers qualify for health and other job benefits.

In every state and city across the country, income inequality has risen to alarming levels … [but] state and local elected officials have at their disposal policy levers that can be crafted to boost low incomes, improve job quality, and create greater opportunities for low-wage workers.

In every state and city across the country, income inequality has risen to alarming levels over the past four decades, and COVID-19’s impact has certainly exacerbated glaring economic disparities. However, in what can be the local equivalent of “building back better,” state and local elected officials have at their disposal policy levers that can be crafted to boost low incomes, improve job quality, and create greater opportunities for low-wage workers. There are no silver bullets with which to quickly reverse income inequality, but as New York City’s example shows, local actions can produce measurable benefits.