Editors’ note: This piece is from Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine’s fall 2023 issue, “How Do We Create Home in the Future? Reshaping the Way We Live in the Midst of Climate Crisis.”

I’m Idi, and today’s my lucky day! The weather dome in Sector 99 isn’t leaking sludge for once, and the artificial sun isn’t stuck at max setting again—I mean, just last week, it was warm enough to melt the soles of my rubber slippers. The air filtration systems are still belching purple gas, but those never bother me anyway: I’ve breathed in DTE micro matter since birth; that sharp and tangy smell soaks in my lungs. I bet that’s how lemons smell, this burning sensation in the back of my throat. Or like Mama used to say, “The smell of dead dreams and empty promises.” I wanted to ask what she meant, but she got sick a while back and just—stopped talking. One of these days, I’ll get my hands on a real lemon, too. Maybe Mama would feel better then.

High above, the weather dome shifts. The sky turns half a shade darker from the usual yellow. A digital beacon displays the current air temperature—a breezy 45 degrees Celsius. Perfect for a day outside. With a skip in my step, I make my way up to the hills outside town. A river of plastic bottles flows fast along the gravel road.

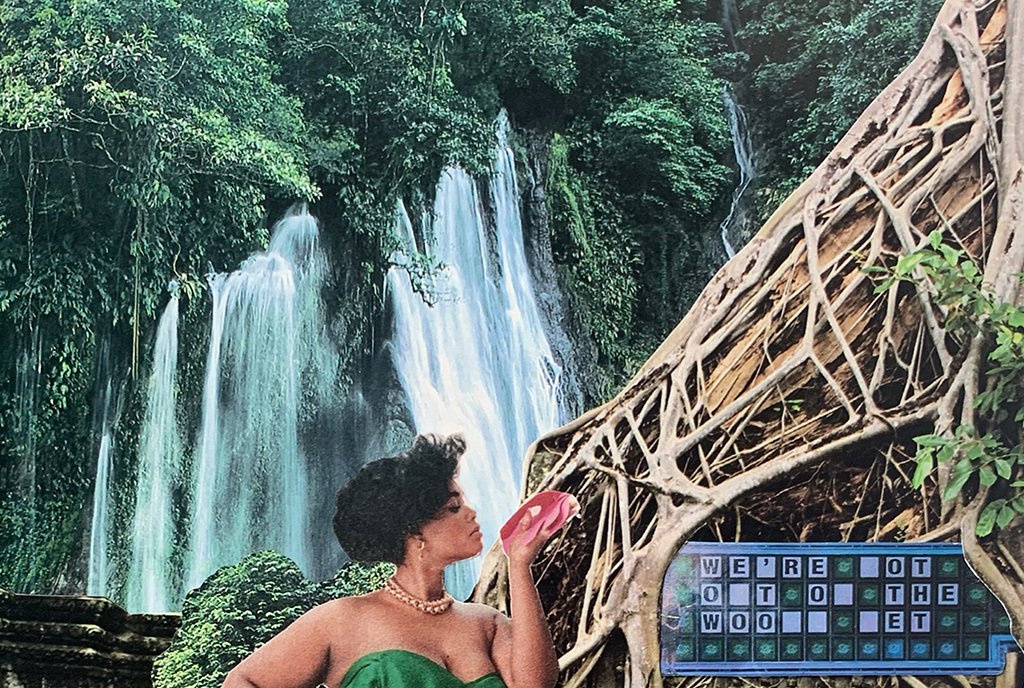

They call Sector 99 “the Junkyard World,” all rot and rust—but I heard it wasn’t always like this. Papa told me about it before he died in a collapsing oil rig late last year. There used to be “trees” and “rolling oceans,” “rock towers” and “floating islands,” beautiful places where our ancestors once worshipped the Anito. Papa said they were fickle spirits—ancient guardians of the space, who lived as unseen ghosts. They would help good kids in need and punish those who hurt their favorite people.

But those were the old days. Barely anyone remembers the Anito now. Papa couldn’t even tell me what an ocean feels like in your hands. Apparently, nothing survived the War—and there’d been hundreds, no, thousands of Wars in every sector of every galaxy. Even now, War is happening in Sector 100 right above us—all the empty bullet casings and rocket debris funneled down to our Junkyard World, still smoking hot. I’ve never actually been to a War, though. I wonder if they have lemons there?

Speaking of junk, today’s batch came down from the sky just now—broken ship parts, scrap metal, and crushed tanker bits raining over the garbage hills of Sector 99. But it doesn’t stop there. Blades, barbs, more bullets—sometimes arrows and swords and nail bats with chunks of skin still stuck to them, and nuclear shells and plasma ray boxes. They pile up high toward amber skies, towers of trash. It takes a lot of work to sort through everything, so the guys up top don’t really bother. I guess they’re too busy with their War and other stuff.

That’s where kids like me come in!

“Tabi tabi tabi!” I chant, while passing through thick brambles, dead wiring. “Tabi tabi po!”

The messy trail opens ahead of me. Rusted chains stirring like vines and huge circuit boards falling flat like stairs before my feet. Bent poles lean in from one side, and I pick out some swollen batteries to put in my sack. Some used syringes over here, and grenade pins over there. Whatever catches my eye. Everything gets sold by weight, anyway. The junkshop isn’t picky so long as I don’t grab anything too bulky.

“Tabi tabi tabi!” I keep chanting. “Tabi tabi po!” It’s an old phrase Mama taught me, back when her voice still worked. She said it was only polite to announce ourselves when walking through any wilderness. After all, the Anito might still be watching over their homes. Mama warned me, too: “The Anito never forget, and they never forgive.”

So I make sure to always remember my manners. And somehow, it’s easier for me too. Somehow, the space goes—soft. My body feels lighter when I move, and it’s like wind lifting me up, just a little, whenever I run, hop, or jump from mound to mound. I don’t really understand, but it feels nice. Here in this Junkyard World, I get to be as free as an angel bird. No strict rules, no nagging teachers, and no stuffy classrooms. No boring books, or homework, or schoolyard bullies. Come to think of it, I haven’t been to school in a long time. But that’s all right. I like it way better out here. I like it when my eyes tear up from the smoke, and I like it when the air burns me from the inside, cuz then I get to pretend that I’m eating lemons.

“Tabi tabi tabi,” I say. “Tabi tabi po.”

So, of course I never forget to pay my respects. I never forget the stories from Papa or the last words that Mama ever said to me. Most importantly, I never forget the Anito.

That’s why today’s my lucky day.

When the string on my half-melted slipper finally snaps, I don’t fall straight into a pit of shrapnel. Instead, I glide over the jagged slopes like a single angel feather wafting in the air. When a hole rips in my sack, I lose all the junk I’ve gathered—but then I find this odd piece of metal, like a thick dinner plate, hidden among the rubble. It glows a bright and colorful light—colors I’ve never seen. Then I remember when another scavenger brought one back. It sold for a lot of money. Maybe ten times more than what I usually earn in a day.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The plate stops glowing as soon as I touch it. A special type of metal? Maybe plutonium, or freisium. Kronium? I have no idea. Either way, if I sell this I could buy all the lemons I want! Mama would be so happy. And Papa—if he were still alive, I know he would be proud. He could probably tell me what the plate is made of, too, but I can just ask the junkshop.

Oh boy, oh boy.

Today’s my lucky day.

Today’s my lucky day!

“Tabi tabi tabi!” I chant as I leave the garbage hills. “Tabi tabi po!” I chant, as I come up to a new checkpoint on the gravel road.

There’s barbed wire and red paint—and a bunch of cop cars, parked beside the river and its rumbling current of plastic bottles.

“Tabi tabi po,” I say again, “Tabi tabi po.” But my voice shrinks as policemen surround me, towering in their full body armor, gas masks, and steel-toe boots. I can’t see their faces. I can’t see their eyes. “Tabi tabi po.” It’s no use. They’re calling me a criminal—but it’s supposed to be my lucky day, I can’t go to jail! They’re saying it’s illegal, what I’ve been doing—picking up trash on the hills. Because it’s private property, because it’s trespassing. But if I get arrested, who will take care of Mama?

Now the cops are saying something else. They’re giving me a chance. We’ll pretend that I never came out here today, so they’ll have to remove all “evidence” on me. But I only have this metal plate. The cops are calling it an “Inactive 474.” A dud shell, though still worth a fortune on the market. They say they’ll take care of it for me so I won’t have to go to jail. But I need that money. How else am I going to feed my sick mother? They can’t take it. They can’t, they can’t, they can’t.

I guess I’ll never get to buy those lemons after all.

The cops let me go. I walk away empty-handed. I make it to twenty steps before I give in and turn my head for one last look at the plate. Through stinging tears, I struggle to see the cop’s silhouette, with his gun pointed right at me, and, oh—they were going to kill me from the start.

The cop pulls the trigger.

Bang.

The bullet flies, but it never reaches me. In that moment, the “Inactive 474” erupts with a blinding light. It wasn’t a dud after all. The explosion kills every cop on the ground, turning them to dust in an instant, armor and all. Cop cars fold and crumble away. The river of plastic disintegrates into nothing. A powerful gust sweeps me high into the air, and it feels like riding on a cloud, soft and gentle. Something cold hits my face then—droplets of water, salty on my tongue. I look down to find water bursting upward from the riverbed, a huge spring that cleanses the amber skies of Junkyard World.

The ocean opens above me—bright, brilliant blue.