June 12, 2018; Los Angeles Times

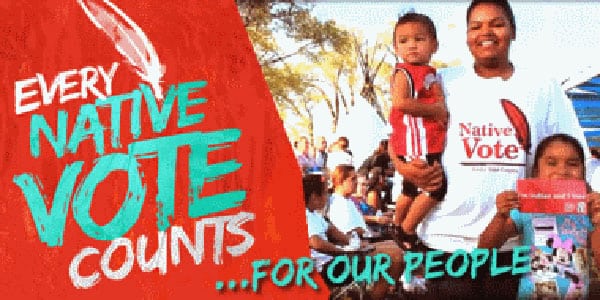

Arizona is not only a battleground in this year’s midterm elections, but it is home to the nation’s third-largest American Indian population. In the state, the census estimates that American Indians number 371,605 people, an 11 percent rise from 2010 to 2016.

“We’re being honest with our voters, saying, ‘We need you to vote,’” explains Angela Willeford, special assistant to the president of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, just east of Scottsdale. “Our ancestors couldn’t vote, but we can.”

Voting for American Indians has not come easily. Marisa Agha in the Los Angeles Times notes that it took a legal battle that was resolved in 1948 for American Indians in Arizona to gain the right to vote. “More recently,” notes Agha, “some say a lack of polling places in Indian Country and restrictive voter registration forms that do not accommodate rural or remote addresses have suppressed the Native vote in the state.”

These present barriers echo a claim of Philip Alston’s recent United Nations report on US human rights, which emphasized the prevalence of various forms of “covert discrimination” in communities of color, including “the imposition of artificial and unnecessary voter identification requirements, the blatant manipulation of polling station locations, the relocation of Departments of Motor Vehicles’ offices to make it more difficult for certain groups to obtain identification, and the general ramping up of obstacles to voting, especially for those without resources.”

According to Agha, “In 2014, the last midterm election, the average voter turnout at polling locations on or near reservations was around 37 percent, while about 48 percent of all registered Arizonans voted, according to a report by the Indian Legal Clinic at Arizona State University. Many polling locations serving large Native American populations had turnout below 20 percent, the report found.”

Now, pressing fights over land rights and sacred sites are encouraging many more to vote. But challenges remain, and attitudes among American Indians towards voting remain mixed. “The issue of voter participation has pitted the skeptical, wary of broken promises and mistreatment, against those eager to find a voice beyond the reservation,” writes Agha.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“This is a population that is becoming energized and…seeing nontribal elections as increasingly important,” says Jean Schroedel, an advisor to the Native American Voting Rights Coalition and professor of political science at Claremont Graduate University. “There’s something going on at the base that I think is pretty unprecedented.”

Schroedel is coauthor of the coalition’s report, published last January, about barriers facing American Indian voters in Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and South Dakota. Among the findings was that a history of mistrust makes many American Indians reluctant to participate in nontribal elections. For instance, according to Agha, just 16 percent of Native people surveyed in Arizona had trust in local government, which reduces their faith in the election process.

“I think we need to be doing more education about why people should be participating in state and federal elections,” says Patty Ferguson-Bohnee, director of Arizona State University’s Indian Legal Clinic. “You might elect people who actually represent your interests.”

“I want our youth to understand how important it is to be engaged and exercise their power to vote,” said Willeford, noting that healthcare ranks high among residents’ concerns.

“Experts believe,” writes Agha, that the number of Native American voters in states like Arizona could prove consequential in some midterm congressional races.”

Agha notes that many American Indians are running for office this year, including Eve Reyes-Aguirre of Phoenix, “who is seeking the seat of retiring US Sen. Jeff Flake, a Republican. She is running as a Green Party candidate in the state’s Aug. 28 primary.”

Nationally, a record number of American Indians are running for office in 2018. According to Indian Country Today editor-in-chief Mark Trahant, “Over 100 [American Indians] candidates are running for office across the country this year. The Standing Rock protests in the Dakotas were definitely a major part of [mobilization] this year.” Writing for ABC News, Meena Venkataramanan writes that in New Mexico, Deb Haaland’s Democratic nomination for House in New Mexico’s 1st Congressional District, positions her “to likely become the first-ever [American Indian] woman in Congress.” In Idaho, Paulette Jordan, a member of the Coeur d’Alene tribe, is the Democratic Party nominee for governor.

Reyes-Aguirre, an Izkaloteka Pueblo member, said her American Indian identity informed her decision to run for office. “I realized our voices have been falling on deaf ears,” she said. “Every decision we make, we think about how it’s going to affect our children, our families, our people. We need to step forward.”—Steve Dubb