November 6, 2018; Vox

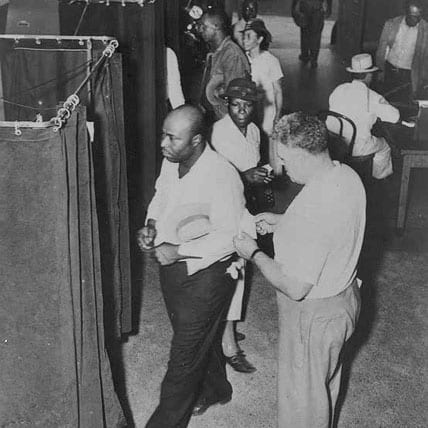

Last week, NPQ’s Cyndi Suarez wrote about the recent “discovery” of white supremacy. A not-unrelated “discovery” comes from the enhanced attention given in the 2018 elections to voter suppression. For nonprofits interested in increasing democratic participation, it is important to have a clear-eyed view of the depth and pervasiveness of the challenges.

As German Lopez observes in Vox, voting rights were on the ballot this fall. By this, Lopez meant voting rights were literally on the ballot in states like Arkansas and North Carolina, where measures to require more stringent voter ID were being considered, and because in many states officials were actively discouraging voting. For example, in Georgia, an estimated 53,000 people—70 percent of whom are Black— had their voter registration applications suspended this fall for infractions as minor as missing a hyphen from a surname. Meanwhile, in North Dakota, the state, as Stephan Cho writes in Paste, has sought to use a strict new voter ID law requiring listed addresses in “a thinly veiled attempt to disenfranchise the state’s Native Americans.”

Often, news accounts treat voter suppression efforts as if they were new. But that’s not so. A few years ago, Arend Lijphart, former president of the American Political Science Association, observed that even labeling the US a democracy before 1965 is problematic, since “many Blacks in pre-1965 America did not have the right to vote.”

Blacks have faced the greatest degree of exclusion from voting, but other communities of color have also faced barriers. Native Americans, for example, were barred from voting until 1924, with full voting rights not extended to all states until 1962.

There are also broader voting system challenges. As Andrew Gumbel, author of the 2016 book, Down for the Count: Dirty Elections and the Rotten History of Democracy in America, wrote in the Guardian, the US political system “has never, in more than two centuries, resolved basic questions of democratic accountability and is thus unique in the developed Western world.”

A case in point, Gumbel observes, are the 2000 elections. We may remember Palm Beach County’s infamous butterfly ballot and hanging chads, but the problems, Gumbel notes, ran deeper than unreliable voting machines. “It also,” Gumbel writes, “became clear that the United States had never established an unequivocal right to vote; had never established an apolitical, professional class of election managers; and had no proper central electoral commission to set standards and lay down basic rules for everyone to follow, free of political interference.”

In the US, we often tell a story of progress. But backward movement can also occur. For instance, at least some women in New Jersey had the right to vote from 1790 to 1807 until those rights were taken away, not to be regained for a century. Historian Kenneth Vickery reminds us that free Black men had voting rights in the early 1800s, including in the South, many decades before the Civil War—until those rights were lost. By 1858, the only states where Black men could still vote were New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In fact, the historical pattern is clear. As Vickery explains:

Virginia and North Carolina joined Maryland and Kentucky in taking from the free Black the franchise he had heretofore possessed. All the new states of the South-west denied suffrage to the free Black man. These processes were paralleled in the American North, where Delaware, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania disfranchised the Black, and New York restricted his to the ballot. The newer states of the North-west allowed no Black voting, access and some of these states even prohibited Blacks from residing within their borders.

[…]

The extension of political democracy among whites, then, was accompanied by retrenchment in the status of Blacks. The point to be emphasized here is that these two processes were part of the same social dynamics.

The result, as Vickery observes, borrowing a term from Pierre van den Berghe, was the development in the US of an herrenvolk democracy, a system where “democratic” rights are restricted to the white “master race”—a system, Vickery notes, that also prevailed in apartheid-era South Africa.

Even after the Voting Rights Act passed, efforts to suppress voting persisted. Between 1982 and 2006, the US Department of Justice and federal courts blocked over 700 changes to election laws found to be racially discriminatory. In 2013, the US Supreme Court weakened the Voting Rights Act by taking away the federal government’s authority to intervene to stop discriminatory laws before they were enacted. But even before the Voting Rights Act was hollowed out, it didn’t protect the voting rights of six million people, many of whom are Black, barred from voting because of past felony convictions.

The state of democracy in the US has never matched its ideals, but progress, while never certain, is possible. One bright note in this fall’s election was the passage of Proposition 4 in Florida. The state constitutional amendment enables 1.2 million convicted felons in Florida to automatically have their right to vote restored. The measure needed 60-percent approval to pass; election returns indicate it carried with a 64.5-percent “yes” vote.—Steve Dubb