September 15, 2019; The Lund Report

Kaiser Permanente is a health care leader in a lot of ways, but they’re subject to the same foibles and strains as any other enormous organization. Kaiser’s labor practices have drawn attention this week as over 80,000 workers threaten to go on strike.

The workers’ petitions will sound familiar to anyone who has been following the United States’ recent years of increasing labor unrest. They ask for:

- A true management-worker partnership

- Safe staffing

- Wage and benefit increases

- A plan to build the workforce

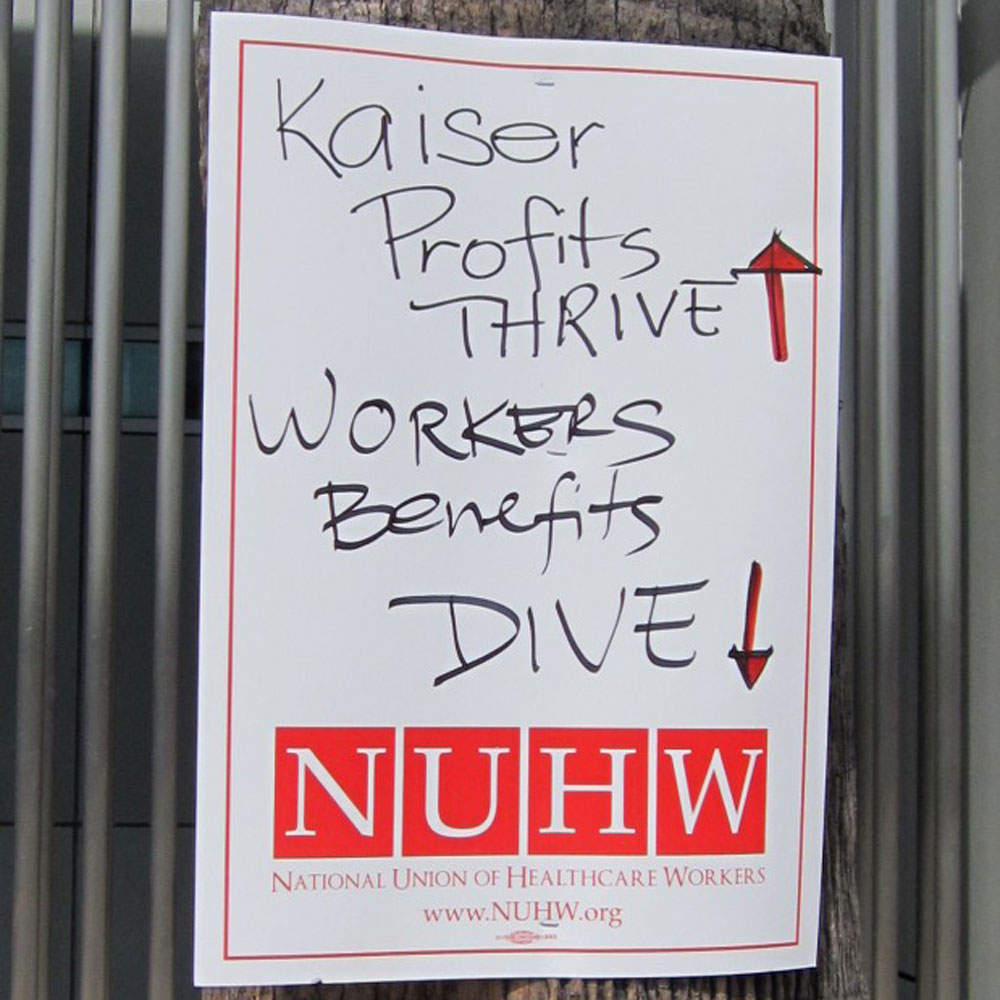

Underlying some of this may be the profit motive, which we have previously discussed with respect to understaffing and low pay at other types of medical facilities, like nursing homes and hospices.

Among the union’s complaints is that managers hired to run Kaiser’s for-profit clinics have become increasingly involved in Kaiser’s hospitals and other nonprofit operations. Workers have complained that managers are asking them to treat growing patient loads and ignoring concerns about understaffing.

Contracts are up at the end of September, and 95 percent of union voters in six states (and the District of Columbia) voted to authorize the strike. That means, as Elon Glucklich at the Lund Report reckons it, that about 85,000 people will walk the picket lines in October if an agreement is not reached.

Kaiser is a unique and complicated organization; they’re what’s called a “vertically managed health system.” They operate nonprofit hospitals that pay salaried physicians, plus for-profit health clinics that are physician-owned and get reimbursed with funds from the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. NPQ has reported how their focus on preventative care has led them to invest in community resource networks and affordable housing support for their communities. Their vertical integration, rejection of pay-for-service compensation for doctors, and focus on preventative care have won them both public praise and explosive growth.

But that growth has had some side effects, say workers and commentators. Glucklich says Kaiser experienced between 5 and 13 percent growth every year for the past decade, but workers say the profits from this growth haven’t been passed on to them or reinvested in better patient care. Membership has grown 15 percent, but nursing staff has been increased less than four percent, resulting in burdensome patient loads.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For themselves, workers are concerned about losing jobs to automation and outsourcing, and say that newer employees are not being offered pensions. They also expressed concern about wage disparity; Kaiser CEO Bernard J. Tyson reportedly makes about $16 million a year.

Workers also expressed concerns about the network not treating enough low-income patients, not investing in sufficient staffing levels for good patient care, and not investing profits in the improvement of the overall system.

Kaiser actually already has a partnership arrangement with its workers. They call it the “Labor Management Partnership,” and it works through “unit-based teams,” comprising one worker, one manager, and when applicable, one physician.

Their union structure is a little complicated. There was a coalition of 12 unions that bargained on behalf of Kaiser Permanente workers, which formed in the wake of huge strikes in the 1990s. Cathie Anderson at the Sacramento Bee explains that a couple of years ago, nine of those unions split off to form the Alliance of Health Care Unions. They reached an agreement with Kaiser last year. It is the remaining unions in the Coalition who are threatening to strike.

They have the money to meet demands. “There is no reason for Kaiser to let a strike happen when it has the resources to invest in patients, communities and workers,” said Eric Jines, a radiologic technologist at Kaiser Permanente in Los Angeles. In 2015, Tracey Seipel at The Mercury News reported that the nonprofit Kaiser Permanente had “$21.7 billion in cash reserves, more than 1,600 times the amount required by state regulations.”

CEO Bernard Tyson described the strike threat as “an overt effort to gain leverage in bargaining.” (Well, yeah…) Executives also described it as “negative corporate campaigning.”

If it goes forward, this will be the largest strike in the US since the United Postal Service strike in 1997.—Erin Rubin

Correction: This article has been altered from its initial form to correctly reflect the number of states (6) that voted to approve the strike. NPQ regrets the error.