Broadly speaking, there are three approaches philanthropy might take to the current crisis. First there is the panicky motion toward austerity, rooted in the fact that endowments are losing value and creating smaller returns that are available for granting. This response calls upon grantees and grassroots organizations of all kinds to figure out how to do more with less, while they clearly need more.

The second approach is toward more: faster and bigger charity. Taking five percent giving as a floor rather than a ceiling, some foundations have accelerated their giving, simplified their application and reporting procedures, and moved more money to important projects. This reflects an appropriate concern for the increased needs, but in the final analysis, it is “more of the same” and limited in its transformational potential.

There is, however, a possible third and final approach, mutual aid, which represents a much needed “something different.” When our foundation, the Fund for Democratic Communities (F4DC), was faced with the choice of “less,” “more of the same,” and “something different,” our direction was clear: something different.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to a greatly increased awareness of the concept of, and the need for, mutual aid, as communities see a set of growing needs whose scale exceeds the capacity that simple charity models can handle.

The national statistic of 36 million new unemployment claims masks the even larger numbers of people who have lived precariously in an informal economy that did not even entitle them to make claims on these government-managed resources. At a local level, it has meant tens of thousands of families without provisions to meet their basic needs. In a crisis of this scale and density, there simply isn’t going to be enough charity to go around.

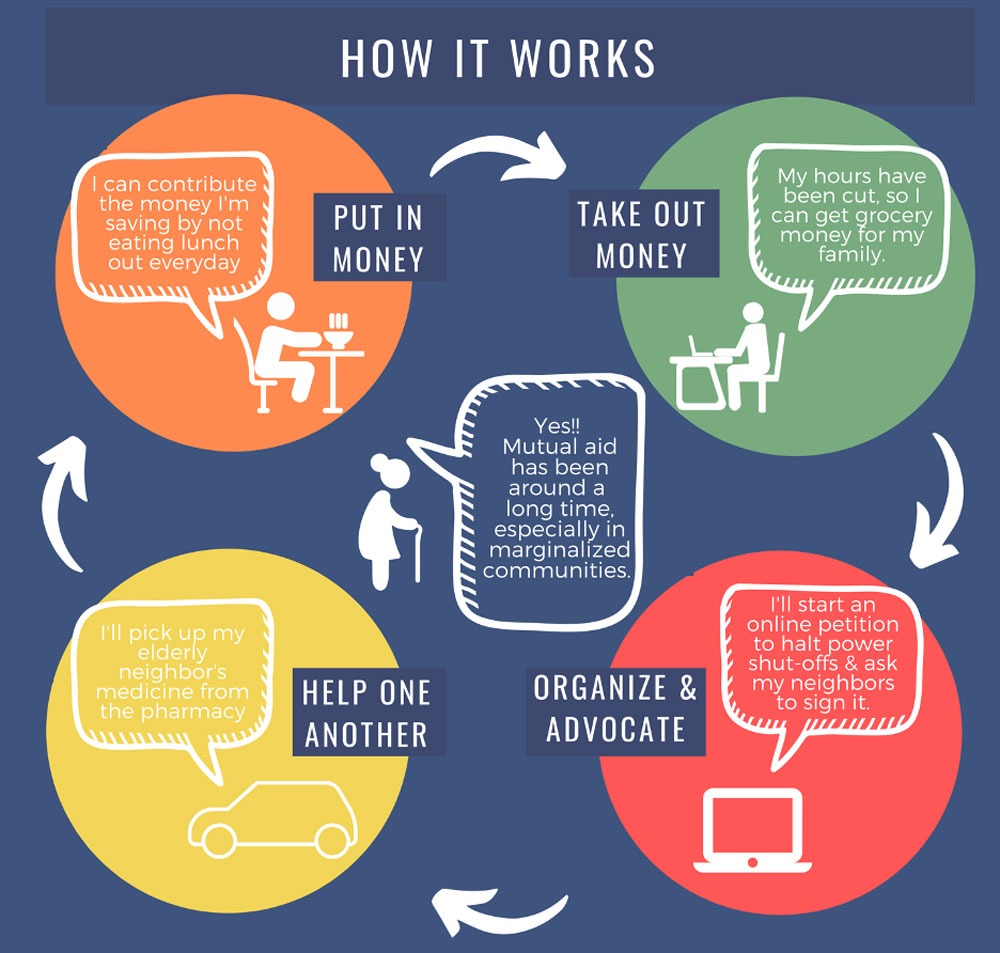

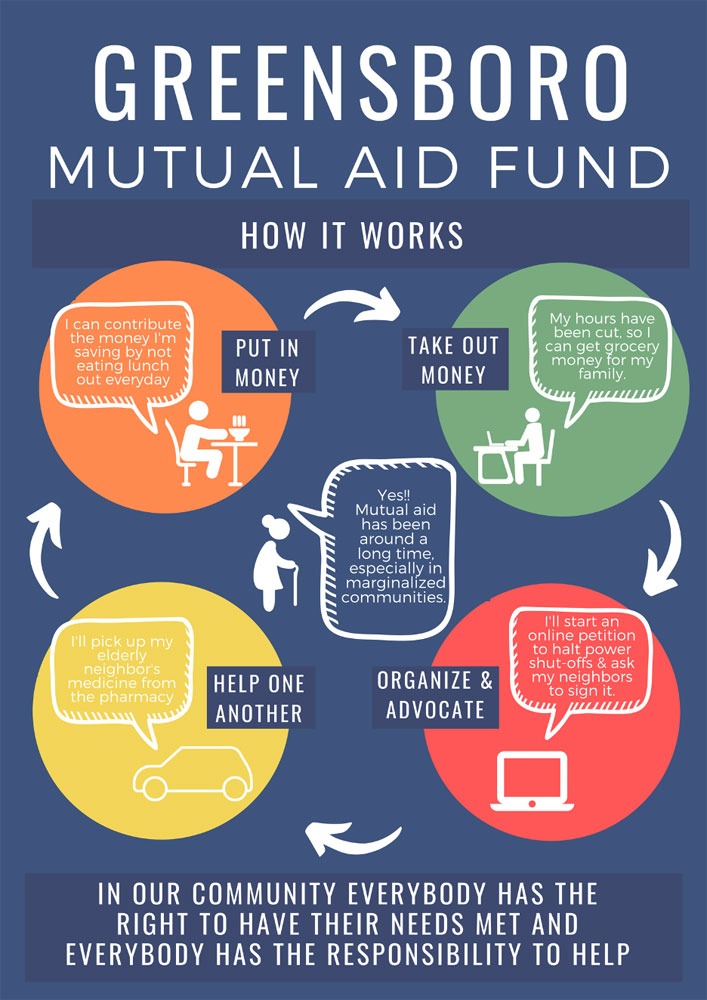

Mutual Aid, based on the idea that everyone has needs that should be met and that everyone has something to offer to help meet others’ needs, activates everyone as part of the solution, and thus has potential to get to the scale we need.

Philanthropy typically focuses on charitable giving, seldom asking recipients to also contribute to the pool of available resources. Mutual Aid roots itself in the notion that if we all contribute, we come closer to making sure that everyone’s needs are met. Mutual aid, in comparison to charity, is not just a transactional exchange, but also a much-needed exercise in being in community with one another.

One way that F4DC has responded to the COVID-19 crisis is by working with local institutional and grassroots partners to develop a Greensboro Mutual Aid Fund (GMAF) as a central component of what we hope becomes an enduring Greensboro Mutual Aid Network.

In the first weeks of the crisis, F4DC met with the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro and YWCA-Greensboro. Together with these local partners, we established some basic design principles for a fund governed by grassroots groups doing the actual mutual aid work in city neighborhoods. The YWCA volunteered to serve as the operational backbone and fiscal sponsor, and F4DC made a $20,000 grant to seed the fund. An appeal was made to the local Virus Relief Fund, which had been organized by the Community Foundation, United Way, and City of Greensboro, but which has a much more limited scope in that it only funds formal nonprofit entities. Thanks to our partners at the Community Foundation, the Virus Fund application resulted in more than $50,000 in additional funds being available in the pool to be given away in local mutual aid work.

A growing number of grassroots groups throughout the city who are doing mutual work were brought together to form a local Accountability Table to oversee the allocation of these resources. Currently, the partners include: Glenwood Helping Hands, the Greensboro Mutual Aid Hub, the Homeless Union, Northeast Greensboro Mutual Aid, Siembra NC, the Rankin Neighborhood Network, Southerners on New Ground‘s Greensboro Chapter, and WHOA (Working Class & Houseless Organizing Alliance). More groups are being invited by the existing groups to join the Accountability Table and access resources. These groups are on the ground, working every day with people who are helping each other meet their mounting needs.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The cash assistance that the groups can now offer is used to strengthen the mutual aid work they were already doing—such as checking in on elders, picking up prescriptions, or finding a donated bed for a new mom who needed to move to a safe location in a hurry. To date, eight groups have provided cash assistance of $50 to $300 to more than 100 people. The work is relational in character, with mutual aid volunteers learning about people’s needs as they “hang out” on zoom calls, Facebook, online mutual aid platforms, and at a safe distance in neighborhoods. When someone gets help—financial or otherwise—they are asked “What can you offer to help us all get through?” The answers range from “I don’t know” to “prayers” to “cook a meal” to “work a phone bank.” Many volunteers have themselves received aid from the fund, illustrating the two-way nature of mutuality.

Like other cities across the globe, in Greensboro, many families have lost part or all of their incomes. The need is great, and it is likely to continue for a long time. The GMAF is designed to be accessible for anyone in need, especially folks who’ve been left out of federal and state government programs. Some members of our communities were already facing struggles that others are just now beginning to face. In many instances, we are distributing money that is literally keeping folks fed, housed, and alive.

In addition to institutional resources, we appeal to individuals and organizations who have the capacity to contribute other resources to the effort, in the spirit of Mutual Aid. As one retiree pointed out, his income had not changed since the awareness of the pandemic, and now he holds the money that he would have been using to eat out and to tip service people. Those same service people still need the money that the tips provided, so he gives regularly to the local Mutual Aid fund and is giving up his stimulus check.

For some of us, mutual aid is something new that has become relevant only as a result of the novel coronavirus. For others, particularly those who live in marginalized communities, mutual aid has been a means of survival for decades. The poor, the working poor, and other members of the working class, both employed and unemployed, have had to rely on family, neighbors, and friends to provide services such as childcare, eldercare, and transportation at little to no cost. Often, these services would be exchanged or bartered for similar services. A mother who works third shift may rely on a friend to watch her children overnight and she may, in turn, watch that friend’s children after school.

There is a long history of mutual aid in the African American community. Due to racism and segregation, many Black people pooled their money to form mutual aid clubs to help bury the dead and provide support for widows and orphans. In some cases, mutual aid groups even provided financial services that were not otherwise accessible, providing personal and business loans and even creating savings clubs to build community institutions such as churches and schools.

Remnants of these informal networks are alive and well today. One such mutual aid group came together in 2018, in the predominantly Black, working class, northeast section of Greensboro, when that area was hit by a devastating tornado. Community members came together and began to provide food, clothing and other basic needs to their neighbors who had lost their homes or had them severely damaged.

It was common to see displaced individuals spend their days working as volunteers to help provide much needed services, often the same services that they themselves received. This same informal mutual aid group sprang into action again when COVID-19 created a new crisis. Like two years ago, individuals who have received assistance through the mutual aid group also volunteered their time to run errands and provide support to their neighbors. Mutual aid and other informal support networks have been and continue to be the backbone for survival within the African American community.

For foundations, properly executed Mutual Aid can over time become a form of institutional—not individual!—suicide. Well-resourced, empowered communities don’t need well-endowed institutional gatekeepers who control access to the society’s wealth. That wealth should be out in the community and facilitating ongoing development that allows communities to meet their needs and improve the quality of life. While the foundations themselves may no longer be needed, that doesn’t mean that the people involved in philanthropy should go away. Rather it means that they will be freed up to engage in community to do their share of the common thinking and building together that is needed to create the world that our children’s children deserve.

While F4DC is ending sooner than we had anticipated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, those of us responsible for building it and developing its work will continue to be active in the communities of which we are a part, and in the community based institutions we have been instrumental in building, such as the GMAF, the Southern Reparations Loan Funds, and Seed Commons: a Community Wealth Cooperative. We have put our resources out into the world where they can continue to be of value to, and in the control of, the creators of the social value that we all depend upon.

Disclosure: NPQ is a grantee of the Fund for Democratic Communities.