October 12, 2020; Brown Daily Herald (Providence, RI)

When the coronavirus pandemic hit the US in March, it became clear that BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] communities—as is true with nearly every crisis or social ill—would be hit harder than white communities. The nonprofit sector would go on to play a critical role in fulfilling community members’ basic needs as both COVID-19 cases and unemployment numbers skyrocketed, and they did so even as they suffered themselves—particularly small, local, place-based nonprofits, which are often BIPOC-led and serving. While these organizations have become more visible as demand for their services spiked dramatically, they continue to receive less support—both public and philanthropic—than other organizations do.

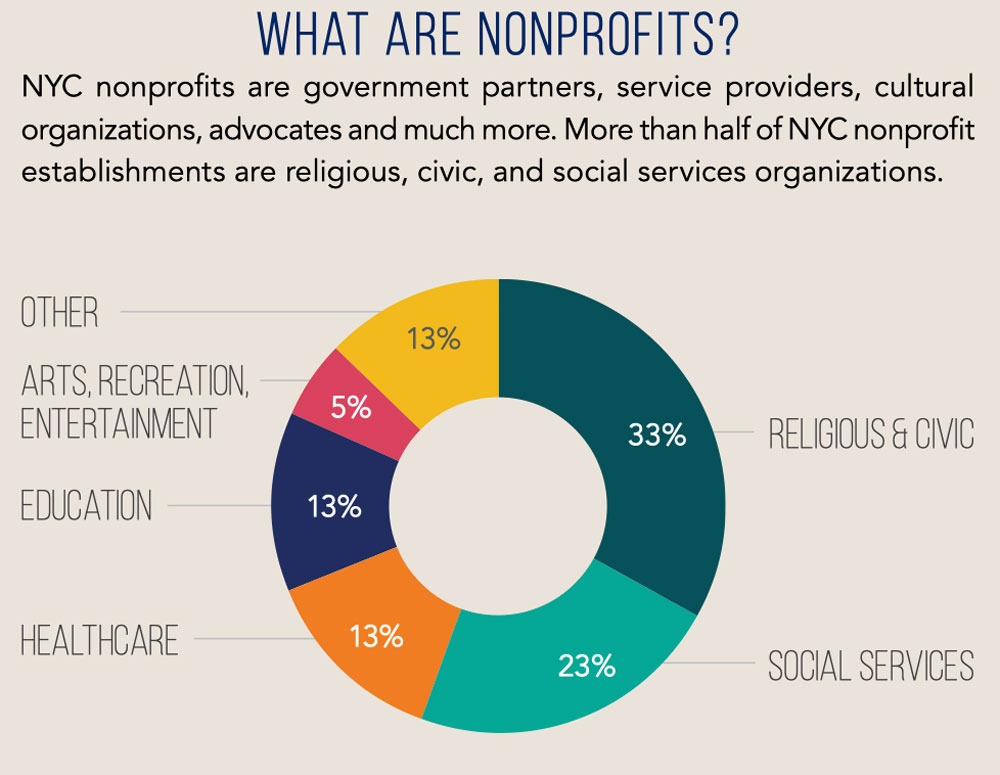

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer addressed this issue in a recent report on the economic impact of NYC nonprofits. The report outlines the $77.7 billion a year that nonprofits contribute to the city’s economy, equivalent to 9.4 percent of the city’s gross domestic product. But Stringer also was clear that the pandemic had placed the health of the city’s nonprofit sector at risk and that nonprofit services were too often the first on the city’s chopping block, with smaller BIPOC-led nonprofits often the most severely impacted. “We can’t nickel and dime the very same nonprofits we rely on to support our most vulnerable communities,” Stringer said in a webinar that followed the report’s public release. “The city wouldn’t dare to treat any other sector this way. They change what they agree to in mid-stream, give you cuts, stop paying you while you’re delivering services.”

Ray Rickman, executive director of Stages of Freedom, a Rhode Island-based nonprofit that pivoted to making and distributing masks after their swimming empowerment programs needed to pause, describes the amount of time he needs to spend to convert $25 donations. “Every morning of my life, I get on the phone and I call six people. Five give me money and it’s not much,” Rickman says. “We have been unable to get any support from anybody with real money. Real charity checks go to the rich.”

John Hope Settlement House, another BIPOC-led, Providence nonprofit that offers an early learning center for preschool-aged children, before- and after-school programs for youth, and other services, had to shut down its in-person services. It reopened in June with changed programming—including, notably, adding services to support youth with distance learning—and has recovered to 90 percent of its pre-pandemic enrollment. Fundraising from local small businesses is largely on hold, however.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This calculus of harder work for smaller dollars gets BIPOC-led organizations stuck in a scarcity cycle. They can often only pursue short-term projects, as opposed to long-term investments, since there’s no strong line of sight to next month or next year’s funding. The time they spend on small-scale fundraising takes away from their capacity to invest in organizational infrastructure and outcomes measurement—often requirements of large funders that, ironically, could pull them off the hamster wheel.

In addition, there’s a significant mental toll of seeing and serving the basic needs of community members and doing it without the resources needed. At the height of the pandemic, Stages of Freedom received 1,400 calls and emails a day from residents desperately seeking the personal protective equipment (PPE) they needed to stay safe and continue their jobs—likely many deemed essential.

“You have to answer them all,” Rickman says.

While the impact this crisis has had on BIPOC-led organizations is disproportionate, and report after report tells us we need to do something about it, there’s still some skepticism that the visibility and support will remain as we head into “recovery.” To date, what we have seen is a “K-shaped” recovery in which the privileged have already rebounded even as low- and moderate-income communities and communities of color face depression-like conditions.—Danielle Holly