August 3, 2018; Boston Herald

Last week, Boston residents testified at a City Council hearing demanding tax-exempt nonprofit institutions pay their “fair share” under the city’s payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) program. A coalition of Boston nonprofits and community groups, the PILOT Action Group, indicates that the “49 largest institutions in the city have failed to pay over $77 million in promised payments under the PILOT program.”

In 2017 alone, the group estimates the shortfall to be $17 million. As a percentage of the city’s budget, this is modest. But it would help the city meet resident needs. As Enid Eckstein and Jonathan Rodrigues write in their report, Boston’s PILOT Program, A Fair Deal for Residents, even $5 million would cover the city’s entire playground renovation budget, or pay for 5-10 miles of new bike lanes, or paving 17 miles of city streets.

PILOTs can be controversial, since nonprofits are typically, although not always, exempt from property tax. (For example, this New York City website notes explicitly that, “Federal 501(c)(3) status alone does not automatically qualify you for the [property tax] exemption.”) PILOTs are most common in the Northeast, but many communities use them. A Lincoln Institute of Land Policy report found that, “As of 2012, at least 218 localities in 28 states had received PILOTs, amounting to more than $92 million per year.”

For our part, NPQ has long acknowledged that nonprofits, while meriting tax exemptions, also have obligations to localities for which PILOTs might be appropriate. Back in 2002, NPQ wrote that, “A healthy PILOT payment ensures that the local community is not, by virtue of foregone local taxes, subsidizing to an unfair degree the broadly accrued public benefit of educating a student body that comes from and will eventually locate themselves all over the world.”

Boston’s policy, developed by a city task force with full nonprofit participation back in 2010, seems to have struck a reasonable balance along these lines. Based on the task force’s recommendations, city policy was introduced in January 2011 wherein nonprofits with less than $15 million in real estate assets were not expected to contribute any revenue to the city, but those with more were expected to contribute 25 percent of the property tax rate. This standard was to be phased in over five years. Nonprofits that provided offsetting community benefits could further cut their payments in half.

The 25-percent standard, although clearly an estimate, was not entirely arbitrary. Rather, as the city of Boston’s website details, the payments were essentially meant to cover the direct share of the costs they bore for basic city services from which the nonprofits directly benefited, like police, fire, and snow removal. As Eckstein and Rodrigues explain, the concept was that “Institutions should contribute for the cost of city services such as snow removal, police protection, etc. Given that these services constituted about 25 percent of the city’s budgets, institutions would be assessed 25 percent of what would otherwise be their real estate taxes.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The payments are, legally speaking, “voluntary,” but all large nonprofits were expected to contribute. As the city website says, the goal was to set a “standard level of contributions…to be met by all major tax-exempt land owners in Boston.” All, not some; standard, not variable.

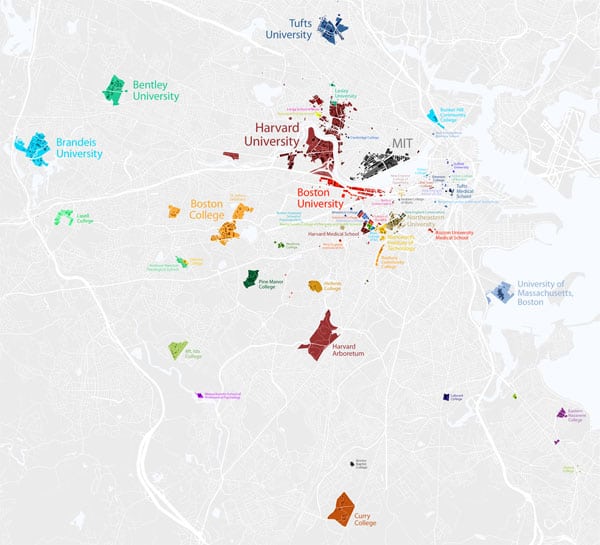

With a few exceptions, nonprofit hospitals have respected the formula, with hospital contributions equaling 94 percent of the expected amount. Look at nonprofit universities, however, and compliance plummets to 61 percent. Sutherland notes that in 2017, “Harvard was requested to pay $6,091,588 for 2017 but actually only contributed $3,201,702. Boston College paid $335,252, which is $1,410,098 less than the requested amount in 2017; while $8,052,510 was requested from Boston University and $6,100,000 was received. Northeastern University paid $1,300,000 which was reported to be $4,181,710 less than the requested PILOT amount.”

Eckstein says the institutions can afford to pay. “We believe very much that these institutions have a responsibility in our city. We believe the PILOT program was a start when it was established seven years ago to look at what is the responsibility of these institutions to our city.”

In an editorial, the Boston Herald was less than sympathetic to the city’s nonprofit universities, opining, “It is ridiculous that these institutions are not meeting their obligations and thus depriving Bostonians of valuable city services and opportunities. It is unfair on its face.”

Councilor-At-Large Anissa Essaibi George agrees, saying “We should hold institutions accountable.” Essaibi George adds that the city council has requested more data from the nonprofits and will take up the issue again soon.—Steve Dubb

Disclosure: The author has volunteered for the Boston Ujima Project, which is a member of the Pilot Action Group coalition.