February 28, 2019; Associated Press

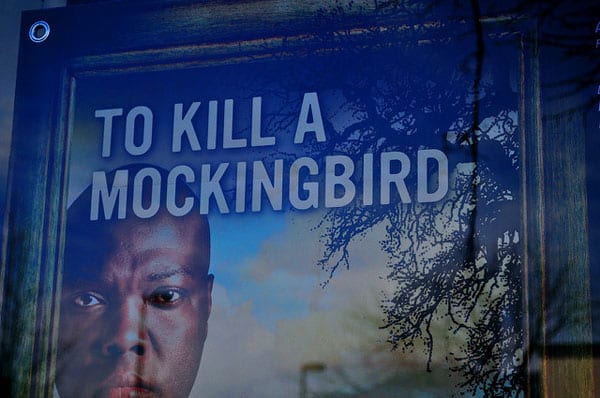

A production of a stage adaptation of Harper Lee’s iconic novel To Kill A Mockingbird has been doing very well on Broadway. Starring Jeff Daniels in the role of Atticus Finch, the show features a script adaptation by Aaron Sorkin of West Wing, Social Network, and Molly’s Game fame. Continuing the saga of arguments, lawsuits, and more that have surrounded Lee and her novel, the producer of the Broadway show, the award-winning Scott Rudin, has sparked a new crisis by demanding that almost all productions of an earlier adaptation of the play be ceased immediately.

In recent reports, Rudin claims that he signed an agreement with Lee granting him exclusive rights to the title. (That agreement was apparently signed in 2015, about eight months before Lee died.) Now, letters have been sent to theatre companies around the world to cease and desist production of any other version. One small community theatre is quoted as saying they were threatened with a lawsuit of $150,000 and so felt no other recourse but to cancel the production. This is even true of productions that were to tour countries in Europe.

Now, stopping for a moment before we bash the evil rich producer, let us recall that legal battles over Mockingbird predate any involvement by Rudin. There seemed to be a dynamic around Lee in her older years where she and her estate battled to exert control over her legacy. Lee, as many may recall, was a recluse throughout much of her life, and kept the boundaries of her work jealously guarded. As much as we would all rather forget that element, it lingers here as a kind of poltergeist visiting itself on volunteer theaters across the country.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Of course, To Kill A Mockingbird is a staple of American literature, and there have been many productions of Christopher Sergel’s adaptation of the play. Sergel began his adaptation in 1970, 10 years following the original publication of the novel. According to one version of the story, with Lee’s permission, the play premiered in 1991 at the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey. Originally intended as a script for middle and high schools, it’s since developed a following in adult community and regional theatres.

That seems to be the major sticking point. Rudin’s stance is that although he hates to see any production of any play be cancelled, the Sergel version is only sanctioned for a limited type of production—presumably educational venues—and that his and Sorkin’s version is the exclusive version for productions intended for adults. Rudin has said he would not stop a production of Sergel’s version if it were for the the kind of venue for which it was originally authorized.

As can be imagined, the ban has caused quite a stir, and a number of theatres around the country are crying foul. In an effort to stop a burgeoning boycott of any Rudin production, new reports suggest that he has offered a compromise: Produce our version of the play and you can go ahead as planned.

Long story short, if there were ever a case of an author haunting her own art, this is it. Lee’s estate also filed suit against Rudin in 2018. Perhaps the whole endeavor needs an exorcism; for now, community theaters must move forward at their own risk.—Rob Meiksins