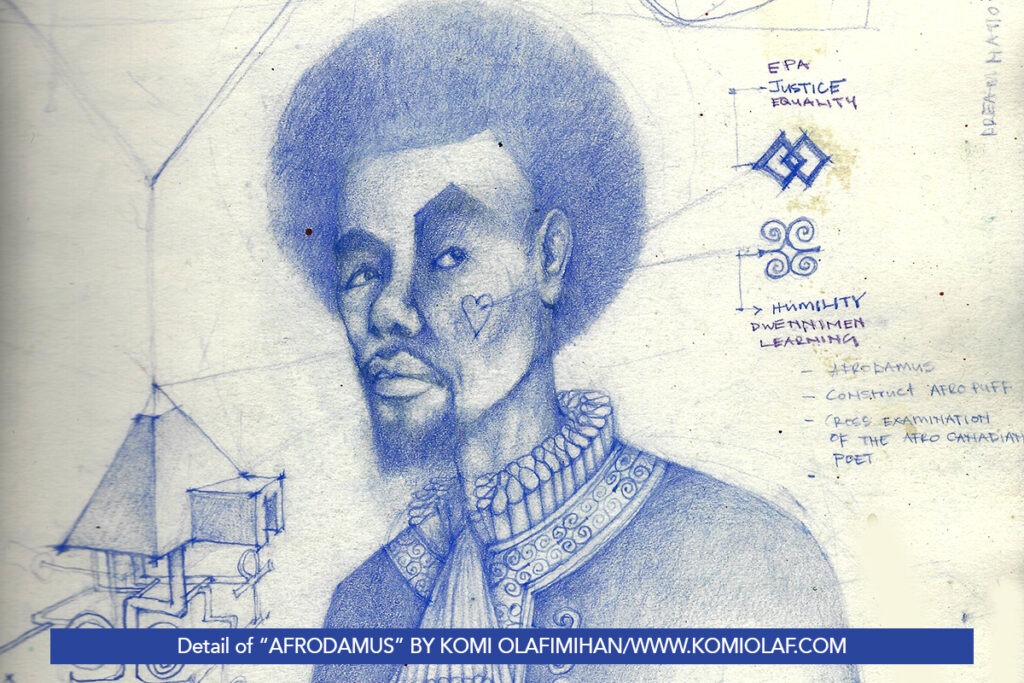

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

Editors’ note: This article is from the Summer 2022 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Owning Our Economy, Owning Our Future.”

I have long wondered how nonprofit institutions such as my own—a Black-led, multiracial organization whose mission is to build more equitable economies—might be able to help develop, invest in, and build alternative financial institutions and infrastructure designed for equity and community wealth. And I have also long wondered how we might engage broader constituencies and communities impacted by our work as coinvestors and co-owners. Admittedly, these feel like daunting questions to imagine and consider, given the long-standing systemic challenges and inequitable dynamics at play in the social sector.

Early on in my tenure as director of Common Future, I attended a funder-organized grantee convening focused on community wealth building. The participants represented some of the most respected institutions advocating for community wealth and equitable distribution of economic power. These institutions were powerful organizers, advocates, and strategists reimagining local, regional, national, and even global economic systems; they were a diverse group made up of grassroots organizers, community development financial institutions, think tanks, and policy advocates, and I was in awe to be in the presence of so much dedicated brilliance. Yet, there was something else that struck me: while these institutions, including my own, were powerfully advocating for and reimagining our economic system to center equity, distributed power, and community wealth, few were actively living out those principles.

Indeed, while many of these institutions supported their own communities and stakeholders to advance community wealth building and new economic models, they often practiced traditional nonprofit economic models themselves—principally, by raising philanthropic capital, most often from foundations. A few had modest fee-for-service revenue models—meaning that they performed contractual work, trainings, or consulting assignments on behalf of government or other clients that could pay for services rendered rather than making charitable contributions. However, much of the discussion that dominated the convening was on how to better organize and strategize to attract additional philanthropic capital, and I was left with a question: Can community-centered nonprofits create alternative economic models better aligned with community wealth building?

The opportunity I see for nonprofit institutions . . . is to become practitioners and exemplars of the economy we want to create. In such an endeavor, philanthropic capital has an essential role to play only so long as the financial resources serve as capital that is fully at the nonprofits’ and organized communities’ own discretion.

That question persists today. Common Future has a diverse body of work. We collaborate closely with a national portfolio of community-based organizations that strive to create economic equity and justice in their local communities. We provide strategic grants, catalytic investment capital, operational support, and thought partnership to a portfolio of community-wealth-building institutions. We work shoulder to shoulder with these institutions to incubate ideas, cocreate new initiatives and strategies, and develop collaborative actions toward shared challenges. But institutional philanthropy was and remains our primary source of capital and revenue.

Over the years, we’ve experimented with various fee-for-service strategies, and we have diversified our philanthropic engagement beyond institutions to include individual donors. As noted by Clara Miller—founder of Nonprofit Finance Fund and past president of Heron Foundation—generating revenue can be a key lever for nonprofits to shift power for themselves and their constituencies.1 But establishing more clarified, expansive, and successful fee-for-service efforts can also miss the mark, because typically they are not directly tied to the goal of building economic power and community wealth—and, critically, the beneficiaries of these earned-income services generally aren’t those for whom economic power and community wealth building would be most transformative. Instead, financially sustainable fee-for-service models are usually aimed at government, foundations, and other individuals and institutions with financial means. Indeed, we’ve found that fee-for-service models often do not have the transformational effect of liberating nonprofits and communities from philanthropic constraints.

Funding For Economic Power

The opportunity I see for nonprofit institutions such as Common Future is to become practitioners and exemplars of the economy we want to create. In such an endeavor, philanthropic capital has an essential role to play only so long as the financial resources serve as capital that is fully at the nonprofits’ and organized communities’ own discretion—in other words, so long as the capital is tied not to programmatic outcomes aligned with philanthropy’s interests but rather to helping build the economic power of the grantees. And how they then decide to use and leverage philanthropic capital must be up to the grantees themselves.

Common Future imagines a world in which people, no matter their race or ethnicity, have power, choice, and ownership vis-à-vis the economy. Since its founding, in 2001, we’ve advised, supported, and intermediated relationships and resources on behalf of more than two hundred community- wealth-building institutions across the country. We’ve worked directly with numerous place-based foundations to shift more than

$280 million from Wall Street investment holdings to BIPOC and rural communities. It took us nineteen years to develop enough of a surplus to (in partnership with our board) grow our operating reserves to cover six months of operating expenses—and we established a fund to meet unanticipated opportunities and challenges without needing to rely on fundraising efforts. Of course, we did not predict nor account for the COVID-19 pandemic. We decided to use the full fund, $250,000—10 percent of our operating budget at the time—to deploy rapid response grants to our national community-wealth-building institutions led by and serving Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people, people of color, women, LGBTQIA folks, and rural communities.

And we did it quickly. While the total funding we were able to make available was small in relation to the scale of the problems facing institutions and communities, all told, the institutions we funded collectively employed over four hundred full- and part-time staff, and supported thousands of small businesses, entrepreneurs, artists, and nonprofits—all vulnerable to and facing a significant economic crisis.

In the months to follow, there was a steadily increasing drumbeat calling for increased access to capital for small businesses, nonprofits, and entrepreneurs—particularly those from communities prioritized by organizations such as Common Future. As emphasis on access to capital became more mainstream, one of the lessons my colleagues and I learned from our experience with our own funding was that control of capital was equally—if not more—important than access to capital. We determined the use of our board-designated fund; we did not have to negotiate with a funder or some other external party. We had the power and control.

Access falls short, because it does not necessarily equate to power. The community-based organizations we work with at Common Future demand and deserve economic power. The people inside these organizations are members of the communities they represent and serve. These organizations and communities oftentimes toil tirelessly to conform to the whims and interests of external parties to pull together adequate resources from funders and others for their visions. Sometimes they have access to these resources, but rarely do they have control of them. And because they don’t have control, they are typically constrained by what other individuals and institutions believe is best for their organizations and communities. During the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, communities of color and rural communities were largely ignored by banks and federal agencies.2 Rather than put decision-making under the control of community-based organizations, resources flowed to and at the discretion of institutions far removed from communities that were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.3

Thus, control of capital was the underlying principle behind the Character-Based Lending Fund (CBL) that Common Future developed in 2021, in collaboration and partnership with ConnectUp! Institute, MORTAR, and Native Women Lead—three community-based small-business and entrepreneur support organizations servicing primarily Black, Indigenous, and Latinx entrepreneurs in Minnesota, Ohio, and New Mexico, respectively.4 Rather than setting the terms and convenants ourselves—as, typically, investors do in an investment transaction—we recognized that we had an opportunity to share and cede our power as the primary resource holder to our three community-based partners. After all, they were essential to the fabric of their communities and intimately understood their needs and opportunities. We asked them to determine how Common Future’s capital would be put to use. We gave them control and decision-making authority with respect to, for instance, what interest rates should be paid on the loans that were given, who received the loans, and the qualifications for receiving them. This process has continued to inform how Common Future collaborates with our investee-partners, with a strong focus on cultivating intentional relationships that are values-aligned, reciprocal, and mutually beneficial.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Imagine the possibilities if community-based organizations, nonprofit institutions, and community-wealth-building institutions of different forms were able to establish genuine economic alignment, economic reciprocity, and mutual economic benefit with our communities, stakeholders, and partners!

The Tension

Still, the primary driver behind Common Future’s ability to build and subsequently share capital and economic power remains predicated on our capacity to raise and attract philanthropic resources. As was the case a few years ago, strategizing how best to attract additional philanthropic capital continues to be at the forefront of Common Future’s business and revenue model, even as we set clear goals to build economic power, agency, and independence. Despite using philanthropic capital creatively to achieve our aims, the tension is palpable.

Unrestricted, long-term gifts have been essential for Common Future to establish a modicum of economic power, agency, and independence. Indeed, we’ve been privileged to be able to raise unrestricted philanthropic funds to support and advance our vision of economic justice for all—especially as a Black-led, multiracial, and majority POC organization: According to the Echoing Green and Bridgespan report Racial Equity and Philanthropy: Disparities in Funding for Leaders of Color Leave Impact on the Table, Black-led semifinalists for the Echoing Green Fellowship reported revenues that were “on average . . . 24 percent smaller than the revenues of their white-led counterparts,” and “[t]he unrestricted net assets of the Black-led organizations are 76 percent smaller than their white-led counterparts.”5 While the report is specific to Echoing Green applicants, it speaks to the broader racial disparities in the nonprofit sector.

Imagine the possibilities if community-based organizations, nonprofit institutions, and community-wealth- building institutions of different forms were able to establish genuine economic alignment, economic reciprocity, and mutual economic benefit with our communities, stakeholders, and partners!6 How might such a transition place power into the hands of communities and institutions most impacted by economic and racial injustice? It is absolutely possible to move away from extraction, exploitation, and concentrated power and toward alignment, reciprocity, mutual benefit, and distributed power—and that may well lead to an economy and world in which race, gender, and place of birth no longer dictate individual and community outcomes.

In fact, it is already happening. There are several examples of nonprofit organizations building economic partnerships with Black farmers and land stewards across the U.S. South, to establish new and democratic forms of financial infrastructure to secure ownership of land and property that benefits residents, farmers, and institutions alike. Land—and Black ownership of land, specifically—is an area that is largely ignored by philanthropy. Land ownership is a mechanism for building wealth and economic power—and it is also used as a means to deny communities rights and resources. Rather than waiting for philanthropy to step in, groups like Potlikker Capital and Manzanita Capital Collective are organizing themselves in various ways as economic change agents—jointly purchasing land with their stakeholders, setting up cooperatively managed financial mechanisms to consolidate opportunities and create scalability, and relying on aligned institutions and impacted communities to create and maintain power and control. Similarly, groups like Higher Purpose Co. and the Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation have leveraged their institutional capacity to assert economic power on behalf of the communities in which they exist.7

For over a year, my colleagues at Common Future worked with Concerned Capital, an organization doing outstanding work in the area of employee ownership and business succession planning. Unfortunately, nonprofit institutions typically don’t consider themselves economic entities capable of creating positive and reinforcing markets among each other, instead often mirroring the same philanthropic practices that are grounded in concentrated power and charity rather than mutual economic benefit and shared power building. Thus, we provided Concerned Capital with a strategic grant, and thoroughly supported and advised them throughout a fundraising process that netted them a seven-figure gift. This is the type of work Common Future is missioned to do, and we take great pride in the contribution we were able to make in this example. But what if this partnership had been structured differently? For example, rather than making a strategic grant and providing pro bono professional services, what if we had structured the arrangement as a recoverable grant and revenue-sharing agreement contingent on the impact of the services and partnership provided? In such an arrangement, we would have established economic alignment, reciprocity, and mutual benefit with our partner.

Such arrangements between nonprofits and their partners, stakeholders, and communities would enable unrestricted philanthropic capital to be used for more disruptive/transformative purposes than simply acting as primary revenue sources. They would enable community-based organizations, nonprofits, and community-wealth-building enterprises to develop self-reliant economic ecosystems between and among their communities, partners, and stakeholders that can be catalyzed by—but not wholly dependent on— philanthropy. They would allow these organizations to build economic power and wealth for, with, and alongside their communities, partners, and stakeholders, rather than relying upon the largesse of philanthropy. It would provide a pathway for all involved to have ownership, control, and power.

For BIPOC-led and -predominant nonprofits to truly catalyze community wealth, we must prioritize building economic power, creating alternative business and revenue models, and establishing economic reciprocity and mutual benefit with our stakeholders and partners. Otherwise, we will contribute to perpetuating the charitable-industrial complex and fail to become equal partners with—or more bleakly stated, continue to be subjugated by—donors and philanthropy.

***

I’m reminded of how financially precarious Common Future was during the first year of my tenure. For starters, I was a new leader succeeding the organization’s founding executive director, which is always a challenging task. Our funding sources were concentrated in fewer than a handful of institutions, and all of their commitments lapsed beginning my first year. We worked diligently to renew their commitments, but we had more to achieve than what was budgeted for—namely, undergoing a rebranding process that would set the stage for our long-term organizational health. Of course, we didn’t have the financial resources to accommodate a rebrand, no matter how necessary it was at the time (and has proven to have been).

Fortunately, we had a donor who understood the value of our request and funded a portion of the rebrand— and, just as important, introduced us to an aligned creative agency start-up. This pairing was crucial—while we couldn’t afford the rebranding engagement at the time, the agency understood the long-term value in working with us. But they were a BIPOC start-up themselves, and couldn’t afford to execute the work without appropriate compensation. We collaborated to determine an aligned, reciprocal, and mutually beneficial economic arrangement: they stretched their fee structure to nearly eighteen months (a lifetime for an agency), and we championed them to prospective new clients. The agency has grown and evolved in the years since, becoming an instrumental partner in the movement for racial and economic justice. We worked in a manner that prioritized mutual benefit and partnership. We recognized our capacities as institutions to drive economic outcomes for each other.

The story of having to come up with money for rebranding is our particular story at Common Future. But our story speaks to far broader issues in the field. Really, what we are talking about here is a need for working capital—that is, the availability of cash being invested strategically by nonprofits, independent of the confines of program deliverables, to expand economic self-sufficiency over time.

The type of mutually beneficial economic arrangement described above is essential for institutions like Common Future—but we need systemic solutions for the entire nonprofit sector, especially in community economic development and economic justice, not just good fortune that happened to benefit our organization. Of course, we are grateful for the donor’s support that enabled the transition we needed. We’re not an endowed institution—few Black-led organizations are, as evidenced by research conducted by Bridgespan—and every strategic grant we make and every bit of patient capital we deploy currently requires us to fundraise the return of capital to ensure our own institutional sustainability for the short and long term.

It need not always be this way. Without these types of models and ways of operating in place, philanthropy will continue to not only hold the purse strings but also the power to capitalize change. Fortunately, nonprofits are well positioned to develop meaningful and mutually beneficial economic relationships among themselves and the communities they serve to create long-standing economic power that is shared and transformative.

Notes

- Clara Miller, “The Looking-Glass World of Nonprofit Money: Managing in For-Profits’ Shadow Universe,” Nonprofit Quarterly, June 12, 2017, nonprofitquarterly.org/looking-glass-world-of-nonprofit-money/.

- Joe Neri, “A Moment of Choice: Racial Equity, CDFIs, and PPP Lending,” Nonprofit Quarterly, April 30, 2020, nonprofitquarterly.org/a-moment-of-choice-racial-equity-cdfis-and-the-ppp-lending-fiasco.

- Ibid.

- Chris Winters, “Lending on Character, Not Credit Scores,” yes!, November 15, 2021, yesmagazine.org/issue/a-new-social-justice/2021/11/15/banking-bipoc-businesses. And see also Jaime Gloshay and Vanessa Roanhorse, “Moving Beyond the Five C’s of Lending: A New Model of Credit for Indian Country,” Nonprofit Quarterly, October 6, 2021, nonprofitquarterly.org/moving-beyond-the-5-cs-of-lending-a-new-model-of-credit-for-indian-country/.

- Cheryl Dorsey, Jeff Bradach, and Peter Kim, Racial Equity and Philanthropy: Disparities in Funding for Leaders of Color Leave Impact on the Table (New York: Echoing Green and Boston: The Bridgespan Group, 2020), 5.

- This is not pie-in-the-sky The cooperative movement, for example, has had reciprocity (“cooperation among cooperatives”) as one of its core principles dating back to the nineteenth century. For more, see Darnell Adams, “What If We Owned It?,” Nonprofit Quarterly 29, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 80–93, nonprofitquarterly.org/what-if-we-owned-it/.

- See “Supporting Farmers of Color: What is Potlikker Capital?,” Potlikker Capital, accessed May 30, 2022, potlikkercapital.com/; “Shifting power and capital to advance racial & economic justice,” Manzanita Capital Collective, accessed May 30, 2022, manzanitacapital.co/; “Our Mission,” Higher Purpose Co., accessed May 30, 2022, higherpurposeco.org/; and “Building Generational Wealth,” Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation, accessed May 30, 2022, heirsproperty.org/.