October 9, 2020; The Nation and San Francisco Chronicle

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed many things about the US, one of which is the true extent of the gig economy. Consider this: official US unemployment is 12.6 million people. Yet as of September 19th, 25.5 million people were receiving unemployment insurance. While US employment statistics are notoriously faulty, the biggest driver of the difference between those two figures is simple—the gig economy. Because of this, an upcoming ballot measure in California, Proposition 22, which seeks to set the rules for the gig economy, could have enormous impact nationwide.

The measure, supported by Uber and Lyft, seeks to overturn provisions passed by the state legislature last year (Assembly Bill or “AB” 5) that sought to force the ride-sharing platforms (and other employers) to treat many contract workers as employees. Uber and Lyft claim they cannot afford the bill and will leave the state if they cannot get their way, but apparently they and fellow companies DoorDash, Instacart, and Postmates can afford to pour a record-breaking $184.3 million into a “Yes on Prop 22” campaign that, observes Wilfred Chan in The Nation, has ‘blanketed the state with nonstop ads, paid ‘volunteers’ for testimonials, enlisted a right-wing troll army to harass opponents, and added scare messages into the Uber app itself.”

For instance, a rider reports on Twitter that when booking a Uber car, the person received a not-so-friendly message saying, “If Prop 22 fails to pass, riders and drivers will be affected. Your ride prices and wait times are likely to substantially increase while most drivers will lose their incomes.”

And, as Mike Moffett reveals in the San Francisco Chronicle, the tactics extend to the widespread (mis)use of political mailers. As Moffett describes, “The fine print on one mailer says it was prepared by the ‘Feel the Bern, Progressive Voter Guide,’ which is not an actual organization. Neither are the ‘Council of Concerned Women Voters Guide’ nor the ‘Our Voice, Latino Voter Guide,’ whose mailers make the same endorsements as Feel the Bern.” The California Democratic Party opposes Proposition 22, but the mailers, which advise voting for Democratic Party candidates, are designed to fool recipients into believing the opposite.

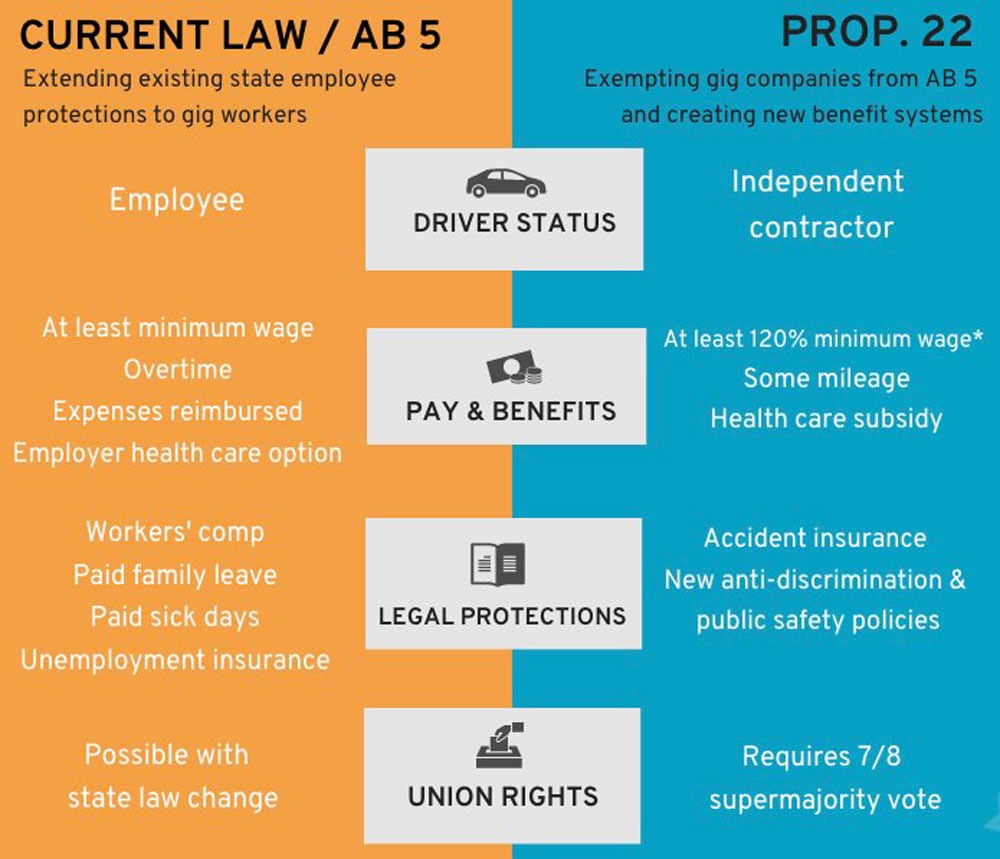

What would Proposition 22 do? Essentially, it would create a new category that would sit somewhere between present independent contractor law and traditional labor law. The law would create some minimum benefits for drivers who drive more than 25 hours a week, including “healthcare subsidies equal to 82 percent of the average California Covered (CC) premium for each month” and some disability coverage. There is also the promise of a “guaranteed” minimum payment of 120 percent of minimum wage and 30 cents a mile, which sounds good, until you realize that the 30 cents a mile may well fall below vehicle and gas costs (the Internal Revenue Service rate is 57.5 cents a mile). The UC Berkeley Labor Center also estimates that after factoring in waiting time, expenses, and taxes, this wage floor established by Proposition 22 would, in fact, come out to $5.64 an hour, far less than the current state minimum wage of $12 an hour ($13 an hour at larger firms like Uber and Lyft).

And then there is the kicker: as Ballotpedia reports, amending Proposition 22 legislatively would require a seven-eights (87.5 percent) vote in both houses in the state legislature; effectively, the only way to amend the law would be to pass another voter initiative through a $100-million-plus gauntlet.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The stakes are high. As Chan explains:

The majority of the “gig workers” who provide the bulk of the labor on these platforms have no other job. They can’t afford to take time off, even during a pandemic. They are predominantly older men, majority Black and brown, often immigrants with no more than high school degrees, and regularly working more than 30 hours a week to support families.

Chan, a onetime part-time driver himself, also details how Uber and Lyft drivers can be available so quickly. The answer is simple: forced overcapacity. As Chan explains, “To make sure customers experience no delays, companies deliberately onboard far more workers than they need, so that they can keep a significant reserve of us on standby, anxiously checking the app, geared up and ready to work.”

He adds, “Because the companies label us ‘independent contractors,’ we are not compensated for this waiting, even though it is essential to the service. Because we can’t set our own prices, our earnings are at the mercy of algorithms designed to waste our time.”

Some drivers, like Chan, for whom the gig is actually a gig and not a way of (precarious) employment can afford to leave. But he adds, most “are locked in—and the bosses know it.” Last month, an amicus brief by the American Civil Liberties Union and National Employment Law Project stated, “Uber and Lyft do not offer ‘opportunities’ to marginalized workers and communities of color. Their misclassification model deepens the desperation of workers who have been excluded from stable employment, with Black and [Latinx] workers made to bear the brunt.”

Will Uber, Lyft, and friends succeed in buying the vote? Only time will tell. Big money doesn’t always prevail. Famously in 1988, an insurance initiative backed by Ralph Nader narrowly passed, even though insurance companies spent $63.8 million in an effort to defeat it. The bill is said to have saved consumers billions. Polls taken in late September show Proposition 22 with a narrow three percentage-point lead.—Steve Dubb