March 8, 2019; Shelterforce

Framing is critical to advocacy work, as all nonprofits know. It’s especially critical when dealing with issues like attempting to redress structural racism, because the unintended—or implied—consequences of a law can end up being its most impactful result.

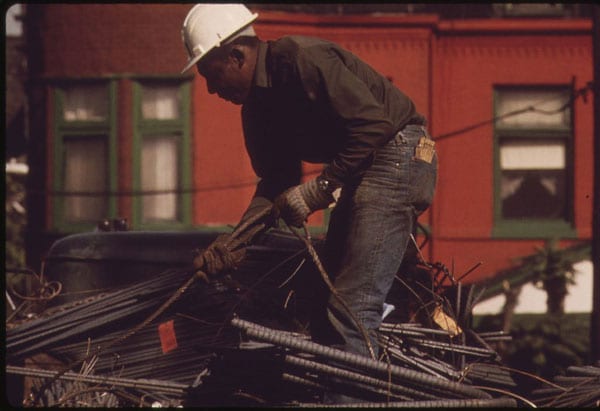

Take, for instance, the Davis-Bacon Act, better known as the “prevailing wage law.” It requires that “contractors and subcontractors performing on federally funded or assisted contracts in excess of $2,000 for the construction, alteration, or repair (including painting and decorating) of public buildings or public works” must pay all their workers, regardless of age, gender, or race, the “prevailing wage” in a county or state—usually the local union-established wage.

Sounds great, right? The construction industry has the lowest gender pay gap of all major industries in the US. (To be fair, construction also has one of the lowest percentages of female workers; in Massachusetts, for instance, seven percent of construction labor union members are women.) Mandating union pay eliminates wage discrimination and benefits many workers.

Except, says Travis Watson of Shelterforce, the law is still achieving its original goal—excluding workers of color from employment on federal construction projects. It’s well documented that the act’s author, Representative Robert Bacon, supported immigration quotas and introduced his wage bill to keep non-unionized black workers from being hired to build a veterans’ hospital in New York. In 1931, when the act passed, black workers were excluded from many, if not most, construction unions.

Watson looks particularly at Boston, where he says the prevailing wage law is “a significant obstacle to Black-owned businesses working in Boston neighborhoods.” Most contracting businesses owned by people of color in the city are smaller, and the paperwork required to comply with federal standards is onerous. Moreover, the union wages that are accepted as “prevailing” are negotiated by union leadership, which is mostly white, and may be unsustainable for smaller businesses, as he says those owned by people of color tend to be.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This might sound familiar to those of us worried about equity in philanthropy. Many small nonprofits run by people of color find it more difficult to get funding due to opaque or convoluted application processes and reporting or performance requirements that don’t make any sense for a smaller, nimbler organization. Requirements that seem neutral because “they apply equally to everyone” are not neutral when some applicants do not have equal access to the resources needed to meet them.

The situation is a little different in the union wage space. It is a good thing to require equal pay, and contractors have been known to skimp on wages to workers who may feel their jobs are vulnerable. So, some kind of wage regulation is needed here.

Boston actually does have diversity requirements for its construction projects, and has for over thirty years. At least 51 percent of journeyman and apprenticeship opportunities on private development projects over 50,000 square feet and any public development projects must go to Boston residents; 40 percent must go to people of color; 12 percent must go to women. Those requirements are making an impact in unionizing historically underrepresented communities: not only is labor union membership in Massachusetts at a 10-year high, but black workers are union members at a higher rate than white workers.

But those requirements are for staff, not for who owns or leads the contracting businesses. People of color still make up a small minority of construction workers overall, even if they unionize at higher rates. Watson’s point is that the wage law makes it harder for smaller businesses, which are more likely than larger ones to be owned by people of color, to win federal contracts, which makes it that much harder for them to survive.

Is there a way to retrofit a law originally meant to exclude people of color into one that benefits them? This question is emblematic of a bigger debate around the function of larger US systems and whether they can be made just or have to be completely reimagined. In order to answer these questions, it’s critical that the discussion’s frame looks at questions of equity, and not just equality.—Erin Rubin