Editors’ note: This piece is from Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine’s summer 2024 issue, “Escaping Corporate Capture.”

When asked to think about corporate capture’s nefarious impact in the world, I don’t have to look very far: Consider my own industry—the nonprofit sector. In the maze of advocacy and issue-based organizations, the tendrils of corporate influence grip tightly, shaping the contours of the sector in ways that stifle innovation and perpetuate inequities, particularly for Black women leaders.

Nonprofit experts have been saying for years that boards are rarely substantively helpful to an organization’s actual work and sometimes are useless or even actively harmful.

Corporate elites, whose focus is on markets and who profess contempt for what they term an “overreaching” government, have continually pushed for (and succeeded in their efforts to achieve) not only massive tax cuts for the rich but also deregulation, financialization of social needs, and the dismantling of our nation’s social safety net. The results of their efforts have allowed corporations to take over government programs, privatize them, and begin working in spaces formerly held by nonprofits. Additionally, in the aftermath of the Enron scandal in 2002, Congress enacted legislation with the aim of fortifying governance practices within corporations and discouraging fraud in the private sector. Nonprofits subsequently embraced numerous provisions from the resulting Sarbanes–Oxley Act to modernize their own governance protocols—leading to a governance culture that, all too often, is at odds with organizations’ practices and goals.1

As the cofounder and copresident of the Maven Collaborative,2 whose mission is to dismantle racial and gender inequality within our economy, I am in a perfect position to bear witness to the subtle yet pernicious ways in which increasingly problematic status quos are maintained in the sector—hindering transformative change and driving talented leaders from our midst. At the heart of this tension is the mirroring of corporate structures within the nonprofit realm—and two in particular: boards and funders.

Nonprofit experts have been saying for years that boards are rarely substantively helpful to an organization’s actual work and sometimes are useless or even actively harmful.3 A 2015 Stanford Business School study found that board directors often lack the skills, experience, and knowledge about the communities served, as well as a solid understanding of their organization’s mission and strategy to address the communities’ needs.4 To be sure, oversight and accountability are important, but boards rarely have enough insight into an organization’s daily operations to handle these duties effectively.

Nonprofit boards often mimic the hierarchical power dynamics found in corporate boardrooms. And the inclusion, over the years, of corporate board members (in the name of “professionalization”) has acted as a conduit for the integration of corporate-sector practices into the nonprofit boardroom. Instead of experts deeply attuned to the organization’s mission and inner workings, such boards often comprise individuals more closely aligned with the interests of the private sector.

These corporate dynamics not only compromise the autonomy and effectiveness of nonprofit organizations but are also contributing to a forced exodus of Black female leaders who dare to push back against the entrenched corporate behaviors.

I experienced this firsthand in my former position as the first Black female president of the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, when the actions of a board misaligned with and uninterested in the important racial justice work of the organization led to my—and then the entire staff’s—resignation.5 While this was a powerful statement against adhering to a corporate-influenced structure that was acting directly against the interests of the nonprofit, such battles disrupt and can even be the demise of an organization.

When the most powerful and privileged individuals—whether they be foundation trustees, donors, or CEOs—promote beliefs grounded in corporate culture (such as competition and toxic individualism) and are dismissive of racial and gender equity, this not only bumps up against the bold ideas and approaches of nonprofits but also minimizes the dreams, hopes, and needs of communities of color and women. It also tethers the nonprofit landscape to the preferences and changing whims of funders. Nonprofits can only be funded for the work that philanthropy is willing to support. For example, when the Ford Foundation, a pioneer funder in supporting racial wealth gap efforts, decided to drop this as a program area in their portfolio, the field suffered immensely.6 No other philanthropic organization stepped in—leaving many organizations scrambling to continue this very important work.

Even the funders who receive accolades for their “disruptive” approach to giving fall into the traps of the corporate world. Known for her surprise donations to small nonprofits, MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving open call effort took an entire year and resulted in a Hunger Games–style clamoring of 6,000 nonprofits for just 250 grants.7 Meanwhile, much of Jack Dorsey’s so-called philanthropic donations went to his famous friends.8

We also see more than just influence, with corporations actually stepping into the role of funder and thus directly shaping the direction of work in the nonprofit sector. Corporate funders often promote the language and strategies of individualism and personal responsibility, which distracts us from reckoning with the systemic economic decisions that are driving racial inequities, and addressing their root causes.

At a recent meeting with a seemingly progressive funder, I was told that the SCOTUS decision had led the foundation to not even mention the phrase “Black women” when referencing its investments.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

And often, corporations are steering the direction of the work with the intent of stymieing transformative change. This can be seen with Goldman Sachs breathlessly announcing more than $2 billion in funding for its One Million Black Women campaign with a vague promise to give to organizations that positively impact the lives of Black women.9 The company claims it’s building an inclusive economy and co-opts the language of social justice movements: as Goldman CEO David Solomon stated, “By investing in businesses that help Black women advance, we can build a stronger economy for everyone.”10 Another way to look at this: the financial firm that admits it defrauded investors through its fueling of the subprime mortgage market that tanked our economy and resulted in the greatest fleecing of wealth among Black Americans in modern history now believes it is in a credible position to decide which organizations offer the most help to the people it ripped off.11

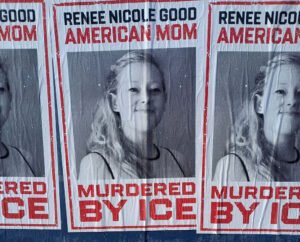

Recent events, such as the Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision spearheaded by a White lawyer named Edward Blum, is an example of political corporate capture that, down the line, impacts nonprofits regarding funding dynamics. First, and obviously, such events further exacerbate the challenge of empowering Black leaders and implementing innovative racial justice work. But second, it directly connects to nonprofit funding: the American Alliance for Equal Rights, established by Blum, filed a lawsuit against the Fearless Fund, an Atlanta-based venture capital firm created to empower Black women entrepreneurs, alleging discriminatory practice. Black women are the fastest-growing group of entrepreneurs in the nation, and Blum’s lawsuit was intended to derail the economic progress of Black Americans and further entrench White supremacy.12 Blum is buoyed by millions from DonorsTrust, dubbed “the dark-money ATM of the right,”13 which advertises itself as a partner for conservative and libertarian donors and includes corporate megadonors from the Koch and DeVos families.14

Despite the affirmative action decision having been limited to college admissions, Blum’s efforts have already wielded significant influence over the nonprofit sector, sowing seeds of fear and inspiring retrenchment among both funders and organizations in the wake of the decision. At a recent meeting with a seemingly progressive funder, I was told that the SCOTUS decision had led the foundation to not even mention the phrase “Black women” when referencing its investments. The recent decision on the Fearless Fund will most likely exacerbate funders’ reticence to support race-specific work.

These recent court decisions have not only undermined the ability of nonprofits to engage in critical racial justice work but also allow corporations to continue to shirk their promised commitments of $50 billion to equity made in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.15 (It is also important to note that many of these pledges were actually in the form of loans from which the banking industry stood to profit—further evidence that corporate influence in the nonprofit world is far from altruistic.16) Even corporations’ own efforts to advance racial justice work are coming under attack due to the affirmative action decision, with DEI programs and diverse hiring facing lawsuits from conservative activists intent on taking our country back to the pre–Civil Rights era.17

***

In the face of these challenges, it is imperative that we confront and dismantle the structures perpetuating corporate influence within the nonprofit sector. We must reject the narrative of fear and instead embrace this moment as an opportunity to fight for justice and equity.18

There is reason to remain optimistic, with bold leaders pointing the way forward. The San Francisco Foundation’s trust-based philanthropic model, for instance, prioritizes building authentic relationships with grantees, centering their expertise and autonomy.19 Similarly, the Monarch Foundation’s efforts to dismantle status quo funding structures, such as lifting bans on unsolicited contacts and ending grant reporting requirements, offer a blueprint for fostering more equitable partnerships between funders and organizations.20 The Maven Collaborative was also the beneficiary of a generous grant from PolicyLink’s Michael McAfee during our inception, a crucial infusion that allowed us to lay the foundation of an organization that would attract more traditional funders.21

But true transformation will require more than just incremental change; it demands a fundamental reimagining of the nonprofit sector. We must move toward a society where corporations and the wealthy pay their fair share, ensuring that the nonprofit industry ceases to serve as a money-laundering scheme to provide tax-free funding for the pet projects of the rich.22

For nonprofits, it means moving from colonized and White-centered structures, relationships, and mindsets to liberated ones. In “Decolonize Your Board,” author Natalie Walrond describes colonized relationships as those in which “one person or group of people prioritizes hierarchy and power over equitable relationships, outcomes, and sustainability.” She continues, “On colonized boards, members may ignore or devalue the expertise, knowledge, and guidance of the leadership team,” and they may become entrenched in a scarcity mindset.23 Organizations committed to equity must recognize “whose values, histories, and aspirations set the [overarching] vision [and direction] of the work.”24 Moreover, nonprofits should embrace alternative structures that share accountability and power, such as coleadership models25 and worker co-ops. By empowering staff and leaders of color, these models not only disrupt traditional power dynamics but also foster a more inclusive and equitable organizational culture.

And for funders, it means a radical reimagining of power dynamics and how success is measured. Organizations should be evaluated for their ability to think outside the narrowly defined box, and actively encouraged to take risks and pursue bold thinking. Those of us in the business of making the world a better place are acutely aware that anything less means a certain death for the liberties we’ve been fighting for all these years: justice, equity, shared prosperity.

Notes

- See Maggie Hagen, “Corporate Capture of Nonprofits: Corporate Law and the Preference for Profit,” Systemic Justice Journal 1 (July 2021).

- See Maven Collaborative, accessed June 8, 2024, mavencollaborative.org/.

- See, for example, “The Problem with Nonprofit Boards ..,” Creating the Future, January 29, 2024, creatingthefuture.org/the-problem-with-nonprofit-boards-is/; Vu Le, “The default nonprofit board model is archaic and toxic; let’s try some new models,” Nonprofit AF (blog), July 6, 2020, nonprofitaf.com/2020/07/the-default-nonprofit-board-model-is-archaic-and-toxic-lets-try-some-new-models/; and Barbara E. Taylor, Richard P. Chait, and Thomas P. Holland, “The New Work of the Nonprofit Board,” Harvard Business Review (September–October 1996), hbr.org/1996/09/the-new-work-of-the-nonprofit-board.

- David Larcker et al., “2015 Survey on Board of Directors of Nonprofit Organizations,” Stanford Graduate School of Business, April 2015, www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/2015-survey-board-directors-nonprofit-organizations.

- Jim Rendon, “Underpaid Black Leader Who Turned Around Social-Justice Nonprofit Resigns, Alleging Racial Bias From the Board,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, December 6, 2022, philanthropy.com/article/low-paid-black-leader-who-turned-around-social-justice-nonprofit-resigns-alleging-racial-bias-from-the-board.

- Darren Walker, “Moving the Ford Foundation Forward,” Ford Foundation, November 8, 2015, www.fordfoundation.org/news-and-stories/stories/moving-the-ford-foundation-forward/.

- Maria Di Mento, “MacKenzie Scott Has Given 24 Nonprofits $146 Million in the First Half of 2023,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, August 18, 2023, philanthropy.com/article/mackenzie-scott-has-given-24-nonprofits-146-million-in-the-first-half-of-2023. (NPQ received an award from MacKenzie Scott in 2021. See MacKenzie Scott, “Seeding by Ceding,” Medium, June 15, 2021, mackenzie-scott.medium.com/seeding-by-ceding-ea6de642bf).)

- Sophie Alexander and Mary Biekert, “Jack Dorsey’s Celebrity Network Is Helping Him Give Away Billions,” Bloomberg, last modified November 22, 2021, bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-jack-dorsey-start-small-donations/.

- “One Million Black Women,” Goldman Sachs, accessed June 8, 2024, goldmansachs.com/our-commitments/sustainability/one-million-black-women/.

- Goldman Sachs, “Goldman Sachs One Million Black Women Deploys More Than $2.1 Billion, Expected to Impact the Lives of Over 215,000 Black Women Across the Country,” press release, April 3, 2023, www.goldmansachs.com/media-relations/press-releases/2023/ombw-announcement-03-apr-html.

- See Eric Levitz, “Goldman Sachs Admits It Defrauded Investors, Receives $5 Billion Fine—But Will Pay Much Less Than That,” New York Magazine, April 12, 2016, com/intelligencer/2016/04/goldman-sachs-admits-it-defrauded-investors.html; Gary Rivlin and Michael Hudson, “Government by Goldman,” The Intercept, September 17, 2017, theintercept.com/2017/09/17/goldman-sachs-gary-cohn-donald-trump-administration/; and Ylan Q. Mui, “For black Americans, financial damage from subprime implosion is likely to last,” Washington Post, July 8, 2012, www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/for-black-americans-financial-damage-from-subprime-implosion-is-likely-to-last/2012/07/08/gJQAwNmzWW_story.html.

- Vaughn Randolph Fauria and Amber Bond, “Attacks on Corporate DEI Are Hurting Black Women First,” , January 24, 2024, msmagazine.com/2024/01/24/business-dei-corporate-work-black-women-diversity-equity-inclusion/.

- Andy Kroll, “Exposed: The Dark-Money ATM of the Conservative Movement,” Mother Jones, February 5, 2013, motherjones.com/politics/2013/02/donors-trust-donor-capital-fund-dark-money-koch-bradley-devos/. And see “A Charitable Partner that Shares Your Values,” DonorsTrust, accessed June 9, 2024, www.donorstrust.org/.

- Jeannie Park and Kristin Penner, “The Absurd, Enduring Myth of the ‘One-Man’ Campaign to Abolish Affirmative Action,” Slate, October 25, 2022, slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/10/supreme-court-edward-blum-unc-harvard-myth.html.

- Jane Nguyen, “A year later, how are corporations doing on promises they made to fight for racial justice?,” Marketplace, last modified May 24, 2021, marketplace.org/2021/05/24/a-year-later-how-are-corporations-doing-on-promises-they-made-to-fight-for-racial-justice/.

- Tracy Jan, Jena McGregor, and Meghan Hoyer, “Corporate America’s $50 billion promise,” Washington Post, last modified August 24, 2021, washingtonpost.com/business/interactive/2021/george-floyd-corporate-america-racial-justice/.

- Julian Mark, Taylor Telford, and Emma Kumer, “Affirmative action is under How did we get here?,” Washington Post, March 9, 2024, www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2024/dei-history-affirmative-action-timeline/.

- Zoe Polk, “Revisiting Juneteenth 2020 and What We Meant by ‘Doing the Work,’” Center for Effective Philanthropy, June 20, 2023, cep.org/revisiting-juneteenth-2020-and-what-we-meant-by-doing-the-work/.

- Marc Tafolla, “San Francisco Foundation Shares Best Practices in Trust-Based Philanthropy,” San Francisco Foundation, November 11, 2022, sff.org/sff-shares-best-practices-in-trust-based-philanthropy/.

- Holly Fogle, “I Know Trusting Grantees Works Because It Propelled My Own Successful Career,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, February 9, 2023, philanthropy.com/article/i-know-trusting-grantees-works-because-it-propelled-my-own-successful-career.

- Jim Rendon, “Racial-Justice Leader Who Left Her Job Alleging Racial Bias by Board Starts New Nonprofit,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, March 15, 2023, philanthropy.com/article/racial-justice-leader-who-left-her-job-alleging-racial-bias-by-board-starts-new-nonprofit.

- Jeff Ernsthausen, “How the Ultrawealthy Use Private Foundations to Bank Millions in Tax Deductions While Giving the Public Little in Return,” ProPublica, July 26, 2023, propublica.org/article/how-private-nonprofits-ultrawealthy-tax-deductions-museums-foundation-art.

- Natalie Walrond, “Decolonize Your Board,” Stanford Social Innovation Review 19, no. 3 (Summer 2021): 27.

- , 31.

- Ben Gose, “No Longer Lonely at the Top: A Growing Number of Nonprofits Hire Co-CEOs,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, October 19, 2023, philanthropy.com/article/no-longer-lonely-at-the-top-a-growing-number-of-nonprofits-hire-co-ceos/.