“Peaceable Kingdom” by Kevin Sloan/www.kevinsloan.com

Editors’ note: This article was first published in the Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development (JAFSCD), in 2011. Facts within pertain to the time when it was written, and some details may have changed. It has been abridged, but the full article can be accessed at www.agdevjournal.com/component/content/article/78-food-value-chains-papers/182-corbin-hill-road-farm-share-hybrid-food-value-chain.html. We thank JAFSCD and the authors for their kind permission.

Food value chains consist of food producers, processors, third-party certifiers, distributors, and retailers working together to maximize the social and financial return on investment for all participants in the supply chain, including consumers. This article presents a case study of Corbin Hill Road Farm Share, a recently created hybrid food value chain that engages nonprofit strategic partners to provide locally grown and affordable produce to low-income residents of New York City’s South Bronx, while also enabling Farm Share members to become equity owners of the farm over time. The case study shows that the involvement of community-based nonprofits is key to creating a food production and distribution system that engages a wide range of stakeholders, fosters shared governance and transparency, empowers consumers, and benefits regional farmers.

The Hybrid Food Value Chain

Elements that distinguish hybrid food value chains from other food value chains and conventional food supply chains include strategic partnerships. But the notion of hybridity in the value chain is not new. C. K. Prahalad and others have argued that cross-sector partnerships can enable corporations to provide needed products and services to low-income consumers by developing innovative products and services as well as appropriate delivery models.1

Strategic Partnerships

Nonprofit organizations are one important element of hybrid value chains, particularly those value chains aimed at meeting the needs of low-income consumers. Nonprofits bring to the value chain social capital that comes from the networks, mutual goals, trust, and beliefs that nonprofit organizations share with their members and stakeholders.2 This social capital—the ability to engage community members, raise funds, disseminate information, and reduce transaction costs—has significant financial value.

Nonprofits can help companies to aggregate and channel demand, lowering transaction costs.3 Their staff members often have organizing skills that enable them to reach out to and attract customers. Nonprofit partners may provide critical insights into the needs and constraints of low-income consumers that they have relationships with as clients, employees, or community stakeholders, and through this knowledge can help in the maintenance of a customer base. Nonprofits also tend to be located within the communities they serve and thus have a first-hand understanding of the logistical issues associated with local business development.

Cocreation of Value

A hybrid food value chain model stresses the collaborative role of value creation by consumers, farmers, for-profit ventures, nonprofit community-based organizations, patient investors interested in social as well as financial returns on their investments, and consumers, all working closely together for mutual benefit. Erik Simanis and Stuart Hart describe this as “business intimacy,” the process by which the private sector cocreates value with nontraditional actors, building connections as companies and communities come to view each other interdependently, developing mutual commitment to each other’s long-term growth.4 And because the needs of the community are part of their mission, businesses and nonprofits are particularly knowledgeable about those needs, and can help customize products and services.

These partnerships can also provide concrete value-adding services: identifying consumers; developing customer trust; communicating effectively with community members about their needs; and identifying innovative ways to address the limited purchasing power of individual consumers.5 Hybrid value chains also help to create business models that span various customer bases.6 If a business can develop a value chain to provide products and services to lower-income customers, it can often provide those products and services to higher-income customers as well, making the model replicable and scalable.

Transparency and Shared Governance

Unlike the conventional food system, the food value chain model treats food producers and processors as partners with consumers.7 But doing so successfully requires procedures to ensure that all parts of the value chain have trust in the fairness and predictability of the partnership through greater transparency than many businesses are willing to provide. Because of the engagement of community-based organizations committed to structural changes that empower the community members they serve, hybrid food value chains are often focused on transforming the food system rather than merely improving its efficiency or increasing access to healthy food. In many cases, the idea of transformation involves creating new enterprises that are inclusionary, participatory, or even co-owned by members. This is the kind of “builder work” that G. W. Stevenson et al. argue is a promising arena for changing the agrifood system.8

Community-Supported Agriculture

As noted above, community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs are one type of food value chain. The idea of community-supported agriculture, in which a group of individuals buy shares from a farmer for an expected harvest, originated in the 1960s in Japan and Switzerland, and spread to the United States following the creation of CSAs by Jan Vander Tuin and Robyn Van En.9 The number of CSAs in the United States has grown from two in 1986 to more than two thousand today; they are concentrated in the Northeast, areas surrounding the Great Lakes, and coastal regions of the West.10

One of the goals of the CSA model is for consumers to support farmers by paying them in advance, sharing the risk of large or small harvests. But CSAs have been established to advance political aims, as well. CSAs promote the formation of direct ties between people and farmers in part to disengage from the global food system and support local economies.11 Many individuals helping to organize direct marketing food initiatives, such as farmers’ markets and CSAs, are also working to solve social justice problems in their localities.12 Research in California found that many farmers’ market and CSA managers prioritized food security for low-income people and used strategies to try to meet the needs of low-income consumers.13

CSAs vary in their structures and business models, including size, cost of membership, growing methods, member involvement, and the food that they provide.14 Since CSAs are highly local creations, they attempt to forge relationships between consumers and farmers that reflect unique conditions and needs.15 For example, although CSAs traditionally require a one-time payment at the beginning of the season for a weekly share of produce, many now offer a range of payment plans and other logistical arrangements, including various selection and pickup methods.16 Some accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and/or Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) payments, offer free shares to needy families, and offer half shares to keep the cost to the members manageable.17

Many types of collaborations occur between CSAs and other farms and community organizations. For example, Neva Hassanein describes a farm run by the University of Montana that collaborates closely with a nonprofit community group, which manages the farm’s operations and the distribution of fresh produce to area food pantries, and also markets its produce through a CSA.18 Along with an increasing variety of payment plans and business arrangements, CSAs are offering a larger range of products, including eggs, meat, and flowers, often partnering with producers of other local products to offer a wider range of value-added items.19

Project Background

Corbin Hill Road Farm (CHRF) was started in 2009 as a ninety-six-acre for-profit farm in Schoharie County, New York. Its core business is supplying fresh, locally grown produce to low-income residents living in communities that have limited availability of healthy food. To do so, CHRF aggregates produce from nearby farms and sells it directly to individuals and organizations in New York City.

The mission of the company is much broader than selling food, however.20 CHRF aims to bring food security, justice, and improved health, as well as eventual economic equity ownership of the farm, to the target market communities, increasing value to all participants in the food supply chain. CHRF’s business model grew out of a sense that, as successful as conventional CSAs are at distributing food directly from farm to consumer, the structure of a CSA is not typically geared toward the financial and logistical needs of very-low-income individuals.

While the basic structure of CHRF operates like a community-supported agriculture program, with customers paying in advance for weekly shares of produce delivered to a pickup location, the business differs from a conventional CSA in several respects in order to address the needs of low-income individuals. One fundamental difference is that CHRF is designed to make Farm Share members, also called Shareholders, farm owners over time, solidifying their relationship to the farm, providing them with greater control over the production of their food, and fostering stewardship of the farmland.21 CHRF’s business plan provides that Shareholders or target market subscribers will be able to own shares in CHRF, though the mechanism for this transfer is still being developed (as discussed further on).

Business Structure and Financing

CHRF is organized as a limited liability company (LLC) incorporated in the state of New York. The decision to seek private financing and operate as a for-profit venture reflected the challenges of an environment in which few foundations were interested in providing start-up funding for new business entities. CHRF’s business plan sought $1.2 million to capitalize the social venture. The initial equity for CHRF came from eleven investors who provided a total of $565,000 (with 72 percent of the equity coming from African-American and Hispanic individuals and 50 percent from women). Capital and operating loans of $350,000 came from Farm Credit East,22 with additional low-interest loans from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). The second round of financing amounted to $450,000 in a combination of equity and loans.

The issue of scaling for social impact is not typically a primary goal of CSAs, but it is a major goal of the Farm Share model. CHRF exceeded its first-year goal of 175 Farm Shares by sixteen members. Throughout the 2010 growing season, enrollment continued to increase, eventually reaching 281 Shareholders—and additional partner sites were added throughout the summer. As of 2011, CHRF’s goal was to have five thousand Shareholders within the next ten years.

Strategic Partnerships

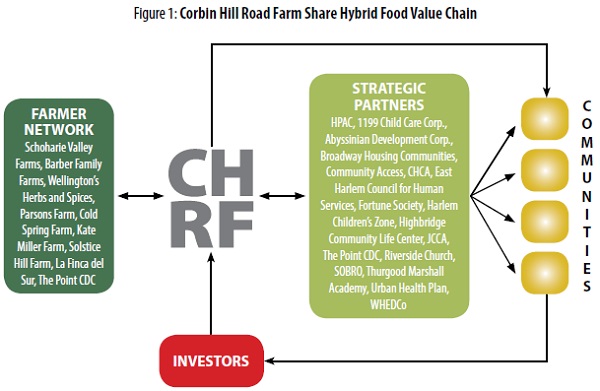

Strategic partnerships enable CHRF to offer a range of produce from various farms and to access its target communities of Shareholders. CHRF unites two clusters of strategic partners: groups of farmers in rural Schoharie County, and community partners within New York City and the Shareholders they represent. CHRF acts as the hub for each cluster and coordinates them so that the two clusters can function simultaneously (see figure 1).

Farmers. CHRF is connected to a network of farms and farmers in Schoharie County who supply produce for the distribution services. Cornell University Cooperative Extension convened a meeting of twelve farmers in February 2011 to help them develop a harvest plan to meet the CHRF’s Farm Share needs. Ultimately, nine farmers agreed to participate. A manual was prepared based on data from the first year, defining the conditions for participation, and identifying the types of produce, quantities, and specific weeks they had to deliver produce for each of the twenty-three-week growing seasons. An agreement was reached about the growing capacity of each farmer and the quantities that could be grown and delivered on specific dates. The latter was important, given the different soil conditions and altitudes that exist in Schoharie County, which could result in early and late crops of the same produce. The mix of participating farmers included two large growers (with more than one- hundred acres), several smaller growers (under twenty acres), and smaller specialty farms that chose to concentrate on new produce (such as okra and tomatillos) not currently grown by the other farmers, that would meet the cultural needs of the communities served by CHRF. A full-time produce manager was hired to coordinate this harvest plan.

Community partners. CHRF’s Farm Share defines community not just by geography but also by the different populations served by its nonprofit partners. CHRF’s business model relies heavily on the strategic community partners in the Bronx that serve the population CHRF is targeting, in order to reach and organize community residents and to form the foundation of a distribution network. Shareholders enroll in the Farm Share program through one of CHRF’s strategic partners—from mothers at the Harlem Children’s Zone Baby College and early childhood and Head Start programs, to ex-offenders and formerly homeless individuals affiliated with the Fortune Society and Broadway Housing Communities, to Bronx-based healthcare workers at Urban Health Plan.

CHRF’s marketing strategies include four basic approaches: (1) CHRF directly organizes residents within a specific neighborhood; (2) CHRF works directly with a strategic partner’s employees and clients (for example, Broadway Housing staff helped to enroll the formerly homeless residents in one setting, and the mothers of children in the Head Start program, which is also operated by Broadway Housing, in another facility); (3) CHRF works to sign up workers and the staff of an organization; and (4) CHRF recruits staff members in some organizations (such as WHEDCo) to introduce CHRF to the organization, build credibility, and demonstrate that it can deliver quality produce on a regular basis, as a precondition to accessing program participants.

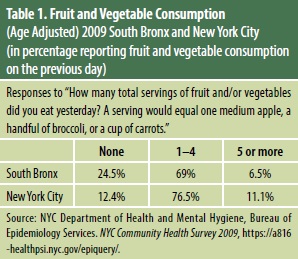

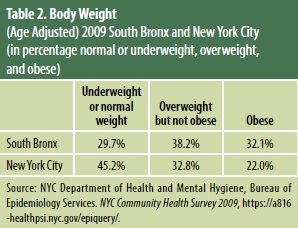

Target Shareholders. CHRF has focused on the South Bronx neighborhood of Hunts Point, whose residents are extremely poor and lack healthy food options. The Bronx as a whole has been ranked the unhealthiest county in New York State, but South Bronx residents face particular challenges.23 For example, a national food hunger survey of U.S. congressional districts found that nearly 37 percent of residents in the Sixteenth Congressional District (which encompasses the South Bronx) said they had lacked money to buy food at some point in the previous twelve months, a higher percentage than in any other congressional district in the country, and twice the national average.24 In addition, per capita fruit and vegetable consumption in this community is significantly below the level in the city as a whole, and far below the USDA-recommended five daily servings (see table 1), and residents are more likely to be overweight or obese (see table 2). Hunts Point has been designated by the Department of City Planning as a community with a lower-than-average ratio of supermarkets to people, with poor access to large grocers even via transit routes.25

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Distribution Logistics

CHRF coordinates the logistics of ordering, packing, and distributing the Farm Share produce. At least three days in advance of a distribution day, the produce manager submits orders to the farmers, enabling them to plan for the quantities of produce to be harvested for the coming week. These “pick orders,” which comprise the combined orders of the Shareholders, consist of ten to twelve produce items, and always include a fruit.

All items are harvested on Monday, then washed, cooled, boxed, and refrigerated in a cold-storage facility located on one of the farms. On Wednesday morning, they are packed into a refrigerated truck that travels to New York City for a mid-afternoon arrival in Hunts Point. The produce is then sorted according to produce type and share at the Fulton Fish Market (a night market that is empty by day) by CHRF’s founder, the driver, a helper, the Farm Share coordinator, and two or three volunteers, and is packed onto labeled pallets for each distribution site. The pallets are stored overnight on CHRF’s refrigerated truck. (One of the community partners installed electrical outlets that enable CHRF’s refrigerated truck to park in an enclosed and locked parking lot each Wednesday evening.) Beginning at 8:00 a.m. on Thursday, CHRF’s driver and helper deliver the produce, and site coordinators (volunteers from the staff of the strategic partners) provide the setup (in farmers’ market style) and distribute the produce during hours that each determines to be convenient for their Shareholders. These coordinators collect funds, sign up new Shareholders, and record any changes in the Shareholder status.

Staffing at CHRF was lean during its first year, and remains so as the business implements its plans for scaling up its operation in the coming years. Operational responsibility is divided between CHRF’s founder, who manages the upstate relationships among the farmers, in addition to overall management responsibilities, and the general manager, who is responsible for the New York City operation and relations with the strategic partners. A farm manager has been replaced with a produce manager. Unique to CHRF is the hiring of a community organizer to engage new Farm Share members. Seasonal positions include a Farm Share coordinator with support staff members who work directly with the strategic partners.

Cocreation of Value

To create a business that is both able to make a profit and address the economic constraints of its target market, CHRF began conversations very early on with community members in Hunts Point about the amount Shareholders would pay and the manner in which they would do so. Typical CSAs charge from $450 to $700 per share, with payments due by early April (and at times as early as January), with the first produce to be delivered in June. For residents living in Hunts Point, paying one to two or more months in advance for a share of produce was not a viable economic option, as the payment required to reserve a CSA share far exceeded their average monthly electronic benefits transfers (EBT/“food stamps”) of $300. Even if they wished to exercise this option, EBT could not be used to pay for fresh produce delivered at some future date. When pushed to decide on an acceptable payment scheme for the fresh produce being provided, Shareholders agreed that paying two weeks in advance was fair and feasible.

Even this commitment proved to be a barrier for many, and during the summer 2010 season, the deposit was reduced to an amount equal to one week’s share. For the 2011 season the deposit has been eliminated; Shareholders now pay only one week in advance. In response to Shareholder recommendations, CHRF also allows share members to give only a week’s notice to put their shares on hold while away, to change from a partial to a full share or from a full to a partial share, and to rejoin after leaving. Shareholders who do not use their funds are given a refund. Some Shareholders are able to pay through after-tax paycheck deductions managed by their employer.

Shareholders have a set number of produce items delivered each week for the twenty-three-week growing season. The amount and variety of produce each Shareholder receives weekly on what is being harvested at any point in the growing season. Partial shares have included seven to nine types of fruits and vegetables in a quantity sufficient for a household of three to four people. Based on feedback from Shareholders who participated in the 2010 season, the per-week prices for the 2011 season were set at $20 for a large share, $12 for a medium share, and $5 for a sampler share that consists of three to five items. All forms of payments, including EBT, are accepted. A limited number of shares subsidized by 50 percent are available for all strategic partner sites that wish to offer them. Deliveries are made at the premises of the strategic partners, staffed by CHRF.

Potential share members had doubts about joining the Farm Share and sought answers to a series of questions and concerns about how to manage their own risks of participating. Questions included: “What is this Farm Share?” “What produce am I really going to get?” “How good will the quality be?” “Would it be sufficient to feed my family?” “Would I really be refunded if I dropped out, or would I be penalized?” For low-income residents who must manage a great deal of uncertainty and risk in their lives, part of facilitating the management of their risks entailed engaging them in the design process, in which they would codevelop the rules of the Farm Share, and, in effect, cocreate value.

Doing so required transparency and shared governance. All information, including written and online material, is produced in Spanish and English. Bilingual surveys are conducted on culturally specific food preferences, individuals are queried weekly about their satisfaction, and weekly meetings of coordinators offer another chance to assess customer satisfaction. CHRF shares how costs of goods and expectations for profits are calculated with coordinators and Shareholders. The Farm Share e-mail newsletter, You Spoke, We Listened, responds to questions.

CHRF also approaches the goal of shared governance by focusing on equity ownership. While the members of a traditional CSA model are, in effect, co-owners of the summer produce, for CHRF co-ownership of the business contributes to sovereignty. One goal of CHRF is for Shareholders to become equity holders who participate fully in decision making about what produce is grown and how it is grown and distributed. However, the exact mechanism for shared ownership has not yet been determined. Two possibilities include creating a cooperative structure and using program-related investment (PRI), through which the nonprofit strategic partners, or even CHRF, finance the purchase of shares for the community residents. The current Shareholders have indicated that they are willing to wait several years to develop a creative solution to two issues: the question of shared ownership that will address the nature of community benefits, and how profits could be used in a collective manner to meet the community’s needs for health and well-being that goes beyond the availability of fresh produce and the long-term preservation of farmland.

Impacts on Shareholders

Anecdotal information from individual members suggests a high degree of satisfaction with the program and the produce. In the words of one member, “Whereas in the supermarket it will cost you more and your vegetables wouldn’t last as long, what’s good about the farm share is you get fresh vegetables constantly every week.” Members also mention trying new types of vegetables: “What’s special about the Farm Share is that you get to try every different vegetable that grows all through the season.” Anecdotal information from members interviewed suggests that they may be increasing their consumption of fruits and vegetables. In the words of one member, “I actually lost eight pounds since I’ve been eating more vegetables and using the farm share vegetables[. . . .] Within two months of eating with vegetables and eating healthy I’ve really knocked out my diabetes, I’m off the medication right now. We have more vegetables in our diets during the week than we’ve ever had before.”

Like the participants in microfinancing programs, there has been peer pressure among the Shareholders to remain involved in the Farm Share. To date, fewer than 10 percent of those who signed up and paid for one week in advance ceased participation before the end of the twenty-three-week season. Preliminary data indicate that the average participation rate was eighteen weeks, including those who joined in mid-season. To the members, governance is an important aspect of the Farm Share, as is the prospect of co-ownership. One member noted: “The real connection that we have to the farm right now is that we will own part of the share.”

The farmers interviewed indicated that they were pleased with the ability to increase their market and help low-income customers eat healthy, fresh produce. The relationship appears to be mutual and value adding for both the producers and the consumers. In the words of one farmer:

Working with Corbin Hill Road Farm is a wonderful thing because it allows us to broaden our customer base. When Corbin Hill doesn’t have enough of a particular vegetable, we may have that overflow, and here on the farm we grow over ninety different varieties of vegetables, so we have quite an array—but the fact that we could send good nutritious food down to the Bronx [. . .] what an unbelievable opportunity for us.

The relationship between the farmers and consumers has grown beyond a mere financial connection. One farmer noted:

It’s more of a relationship opportunity for us[. . . .] Here I was, born and raised in this valley, and I have all this wonderful produce available to me every day of the season. And I think sometimes my neighbors and myself included happen to take that for granted. Being able to send produce to an area where some people, maybe even my same age, have never seen something as fresh and wonderful as we can raise here [. . .] and to hear the feedback that we get from those people when they receive their shares, that’s the biggest reward for me.

Being part of the Farm Share project has also encouraged the farmers in Schoharie County to explore new, value-added crops. According to one farmer:

[CHRF] offers a unique opportunity for us to explore new crops to grow. When we learn more about communities that we’re helping to feed, it will allow us to grow new and exciting crops that may also be well received in areas closer to home for us here, expanding our local markets as well.

The farmers recognize the importance of the NGO partners in the Bronx, too. One farmer noted: “This model [. . .] is really dependent on the people that are spending so much time down in the Bronx, on the ground, getting people interested.”

The farmers in Schoharie communicate weekly with CHRF’s produce manager to discuss what produce is abundant that week and what the Shareholders may like. As one farmer described the interaction:

She may ask, “What’s new or what’s interesting?” “What do you maybe need help with moving?” And I will give her a rundown of suggestions, and she will see what fits into their budget and what she feels their shareholders may be excited about.

Discussion and Conclusions

This article discusses the concept of a hybrid food value chain, and uses that framework to examine the role of nonprofit partners in adding value and fostering transparency within a food supply chain. The Corbin Hill Farm Share functions as a hybrid food value chain, and in so doing has the potential to open up new markets for a cluster of small to medium-size farms within the New York City metropolitan area, while simultaneously supplying low-income residents of the South Bronx with fresh, locally grown produce, and ultimately fostering food sovereignty.

As the case study illustrates, the robust network of nonprofit partners that transformed a simple supply chain into a hybrid value chain was essential to getting CHRF up and running by engaging shareholders and providing critical support services, which ranged from facilitating the payments of certain shareholders to providing a physical storefront for distributing produce. One factor that enables the hybrid value chain to work is that all the nonprofit partners selected for this project have missions that include improving the community’s health and nutritional status, and educational programs to engage members of the community in discussions about health. CHRF carefully chose partners that were working in these areas so that the organizations would not only take a strong interest in the project but also be able to link their educational efforts to Farm Share—so that learning about and practicing healthy eating were mutually reinforcing.

Relatively little time had to be spent formalizing the network of NGO strategic partners: each organization was familiar with the other groups and had opportunities to meet; they shared a common understanding of the problems facing the South Bronx communities; and there was little debate about CHRF’s goals and objectives. CHRF has treated the NGOs as equals, allowing each organization to individually design programs as it sees fit. This policy has also been applied to the individual Shareholders, who helped to shape Farm Share to meet their unique needs and constraints. And without a strong hybrid network of NGOs, there would be little financial incentive for the farmers in Schoharie County to seek out an individual organization within the South Bronx, and attempt the time-consuming and difficult process of building trust and forging a business relationship that might be insufficiently broad to yield an economic return.

The leadership among the farmers in Schoharie County—a closely interconnected community characterized by third- to sixth-generation farmers who are often linked through family ties—provides significant social capital that extends from the township to the county and state level. Their choice to work together on this project was the result of the initiative of a couple of the farmers within the county who were successful at encouraging others to work with CHRF. The Farm Share model may in the future offer participating farmers the ability to expand their production to serve even larger markets. There are more than one million residents living in neighborhoods in the South Bronx and Harlem, poorly served by food retail establishments—a very large potential market. And there are many nonprofit organizations in these neighborhoods that could serve as strategic partners.26

Because CHRF is a recent startup, it faces numerous financial and logistical challenges. As it strives to break even, it must maintain a delicate balance between keeping prices affordable to the community it is serving and—to be financially sustainable—reaching a scale of three thousand Shareholders within a reasonably short period. CHRF also faces the risk of being among the first social ventures in a newly defined space. The business model assumes that CHRF will attract social investors who understand the nature of the “slow money” challenge and will risk investing in this venture over a longer period of time.27 CHRF has thus far received round-two loans and equity to launch its expansion. Those who have participated have taken a long-term perspective that is associated with such food ventures, and have been willing to accept a low return on their investment. Personal guarantees have had to be provided for all loans. The strategy of seeking patient investors represents for CHRF a more stable approach over the long run than seeking to build a venture dependent on grants from foundations or the government, but it remains a challenge nonetheless.

Another major financial issue will be managing CHRF’s costs. Produce purchases make up some 65 percent of the cost of goods, and can be controlled through efficiencies in packing and using reusable packaging. The same cannot be said for transportation costs, which now make up 19 percent of the cost of goods of each share, and will rise if fuel prices continue to escalate. Controlling transportation costs, along with the added expenses of establishing and maintaining refrigeration, represent formidable challenges that CHRF will need to address in the coming years.

CHRF also faces complexities that require the design of systems that will accommodate the flexibility it seeks in responding to Shareholder needs. To remain nimble while scaling up to 1,500 Shareholders in the second year and then to 3,000 in the third year, CHRF expects to maximize its use of technology for its internal management, and has outsourced its registration of Shareholders to Farmigo, an organization that serves CSAs. It is also in the process of outsourcing its trucking operation to a firm that can respond to and accommodate CHRF’s projected growth. CHRF’s staffing has been able to remain lean, since it provides a tool kit to its strategic partners who do the organizing and recruitment of Shareholders.

CHRF’s long-term profitability depends on the ongoing coordination of hybrid networks of producers, nonprofit intermediaries, and Shareholders—a constant challenge for a business that aims to provide high-quality food at a low cost, while attempting to ensure fairness to everyone in the value chain. If CHRF succeeds, the hybrid food value chain may be an important strategy for increasing the participation of low-income citizens in the food system, expanding economic empowerment, fostering stewardship, and providing new markets for the small and mid-size farm sector.

Notes

- C. K. Prahalad, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profit (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing, 2004).

- Herrington J. Bryce, “Nonprofits as Social Capital and Agents in the Public Policy Process: Toward a New Paradigm,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 35, no. 2 (2006): 311–18, nvs.sagepub.com/content/35/2/311.short.

- John Weiser et al., Untapped: Creating Value in Underserved Markets (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2006), 23.

- Erik Simanis and Stuart Hart, “Innovation from the Inside Out,” MIT Sloan Management Review 50, no. 4 (2009): 77–86, sloanreview.mit.edu/article innovation-from-the-inside-out/.

- Valeria Budinich, Kimberly Manno Reott, and Stephanie Schmidt, “Hybrid Value Chains: Social Innovations and the Development of the Small Farmer Irrigation Market in Mexico,” in Business Solutions for the Global Poor: Creating Social and Economic Value, V. Kasturi Rangan et al., eds. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007), 279–88; Ezequiel Reficco and Patricia Márquez, “Inclusive Networks for Building BOP Markets,” Business & Society, published electronically March 2009, bas.sagepub.com/content/51/3/512.abstract.

- Reficco and Márquez, “Inclusive Networks for Building BOP Markets.”

- G. W. Stevenson and Rich Pirog, “Values-Based Supply Chains: Strategies for Agrifood Enterprises of the Middle,” in Food and the Mid-Level Farm: Renewing an Agriculture of the Middle, Thomas A. Lyson, Stevenson, and Rick Welsh, eds. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008).

- Stevenson et al., “Warrior, Builder, and Weaver Work: Strategies for Changing the Food System,” in Remaking the North American Food System: Strategies for Sustainability, C. Clare Hinrichs and Lyson, eds. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 33–64.

- Richard L. Farnsworth et al., “Community Supported Agriculture: Filling a Niche Market,” Journal of Food Distribution Research 27, no. 1 (1996): 90–98, ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/27792/1/27010090.pdf; K. Brandon Lang, “The Changing Face of Community-Supported Agriculture,” Culture & Agriculture 32, no. 1 (2010): 17–26, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1556-486X.2010.01032.x/abstract.

- Katherine L. Adam, Community Supported Agriculture (Butte, MT: National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service, National Center for Appropriate Technology, 2006); “Community Supported Agriculture,” LocalHarvest, www.localharvest.org/csa.

- Julie Guthman, Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); Elizabeth Henderson and Robyn Van En, Sharing the Harvest: A Guide to Community Supported Agriculture (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishers, 1999); Steven M. Schnell, “Food with a Farmer’s Face: Community-Supported Agriculture in the United States,” Geographical Review 97, no. 4 (2007): 550–64, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2007.tb00412.x/abstract.

- Patricia Allen, “Realizing Justice in Local Food Systems,” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3, no. 2 (2010): 295–308, cjres.oxfordjournals.org/content/3/2/295.abstract.

- Guthman, Amy W. Morris, and Allen, “Squaring Farm Security and Food Security in Two Types of Alternative Food Institutions,” Rural Sociology 71, no. 4 (2006): 662–84, caff.orghttps://nonprofitquarterly.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Rural-Soc-food-farm-security.pdf.

- Robert Feagan and Amanda Henderson, “Devon Acres CSA: Local Struggles in a Global Food System,” Agriculture and Human Values 26, no. 3 (2009): 203–17, www.cemus.uu.se/dokument/ke-distans%202009/CSA.pdf; Lang, “The Changing Face of Community-Supported Agriculture”; Steve Martinez et al., Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues, Economic Research Report 97 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2010); Schnell, “Food with a Farmer’s Face.”

- Trauger Groh and Steven McFadden, Farms of Tomorrow Revisited: Community Supported Farms—Farm Supported Communities (Kimberton, PA: The Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association, 1997).

- Timothy Woods et al., 2009 Survey of Community Supported Agriculture Producers, Agricultural Economics Extension Series 2009–11 (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service, 2009), www.uky.edu/Ag/CCD/csareport.pdf

- Lang, “The Changing Face of Community-Supported Agriculture.”

- Neva Hassanein, “Locating Food Democracy: Theoretical and Practical Ingredients, Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 3, no. 2 (2008): 286–308, www.tandfonline.com/doi /full/10.1080/19320240802244215.

- Schnell, “Food with a Farmer’s Face”; Woods et al., 2009 Survey of Community Supported Agriculture Producers.

- See corbinhillfoodproject.com/#f-share.

- Corbin Hill Road Farm capitalizes “Shareholder” as a stylistic choice to distinguish its members from conventional equity shareholders.

- www.farmcrediteast.com/.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, “Health Outcomes Ranking: County Snapshot 2010: Bronx (BR),” County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, accessed February 4, 2011, www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/new-york/2010/bronx/county/outcomes/overall/snapshot/by-rank.

- Food Hardship: A Closer Look at Hunger: Data for the Nation, States, 100 MSAs, and Every Congressional District (Washington, DC: Food Research and Action Center, 2010), frac.org/newsitehttps://nonprofitquarterly.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/food_hardship_report_2010.pdf.

- “Going to Market: New York City’s Neighborhood Grocery Store and Supermarket Shortage,” citywide study dated April 21, 2008, New York City Department of City Planning, www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/supermarket/index.shtml.

- See The New York City Nonprofits Project, “Finding #1: New York City’s Nonprofit Universe Is Large and Dynamic,” New York City’s Nonprofit Sector (New York: The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 2002), www.nycnonprofits.org/exec_summary/h1.html.

- Cf. Woody Tasch, Inquiries into the Nature of Slow Money: Investing as if Food, Farms, and Fertility Mattered (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishers, 2010).