Editors’ note: The following mini–case study is part of a series of studies submitted as part of the graduate course “The Nonprofit Sector: Concepts and Theories,” taught by Chao Guo, associate professor of nonprofit management in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. This article was featured in NPQ’s winter 2014 edition, “Births and Deaths in the Nonprofit Sector.” (Click here to read part one, part two, and part three.) It was first published online on March 9, 2015.

Addendum: After the online publication of this article, we were fortunate to be contacted by Musimbi Kanyoro, CEO of the Global Fund for Women, and Claire Winterton, former executive director of the International Museum of Women and current VP of Advocacy and Innovation at the Global Fund. They shared with us their impressions of the key elements that made their merger a success. You can find their thoughts appended to the end of this feature.

This case study looks at the factors that led up to the decision of the International Museum of Women (IMOW) to merge with the Global Fund for Women (GFW) in March of 2014. While we reached out to previous IMOW staff—now at GFW—for a firsthand account of the events that led to the merger, we were unsuccessful and had to rely upon secondary information for evaluating the two organizations’ financial and strategic decision to merge their staffs, boards of directors, and operations under one shared mission.

The International Museum of Women

From 1985 to early 2014, the International Museum of Women operated as a digital museum, curating exhibitions, producing physical installations and events around the world, and developing an educational curriculum, all in aid of inspiring creativity, awareness, and action on vital issues for women. According to IMOW, approximately 70 percent of visitors surveyed reported changes in their opinions about global women’s issues, and up to 60 percent reported taking action toward gender equity as a result of engaging with IMOW’s digital content.1 But in March of 2014, the museum announced it was shutting down operations as an independent entity and merging with the Global Fund for Women, the largest public foundation in the world dedicated to advancing women’s and girls’ rights through an international network of women-led organizations, advisors, and supporters. But if IMOW was so successful in achieving its mission and advancing global gender equity, what events led to its decision to merge?

A Museum without Walls

IMOW was originally founded, in 1985, as the Women’s Heritage Museum, and for over ten years it operated as a “museum without walls,” producing exhibitions and resources for the public. Jeanne McDonnell, the museum’s executive director in 1995, articulated IMOW’s mission in the following statement: “We have been working for ten years in the field of public education in women’s history. We have not limited our subject boundaries geographically because we believe that women’s mutual concerns transcend political boundaries.”2

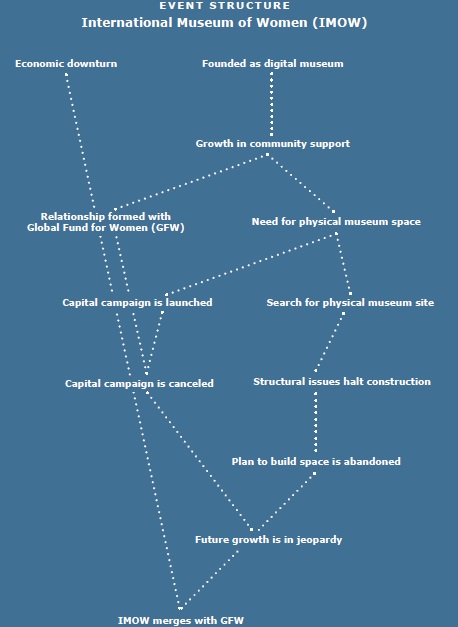

Growing support from the community led the museum’s board of directors to begin plans to create a single-destination women’s museum in San Francisco. In 1994, the museum submitted an application to build a physical space in the Presidio. The plan, which they titled “Shooting for the Stars (A Plan for the Women’s Heritage Museum at Presidio) 1995–2035,” was an ambitious one. The museum envisioned not only building the physical location in the Presidio but also simultaneously building a coalition of similar women’s museums in South America, Africa, China, Japan, and Eastern Europe—along with creating its own television channel, developing a series of educational programs and scholarships, and creating partnerships with other global cultural organizations. However, although its application to lease one of the Presidio buildings was initially approved, political changes derailed all nonprofit efforts to lease space there, and the museum was forced to move in another direction.3 Despite this setback, the board of directors stuck to its decision to look for a physical home for the museum. And, in 1997, the board decided to change the museum’s name from the Women’s Heritage Museum to the International Museum of Women, to reflect the museum’s focus on global women’s issues.

Following the Presidio project, the museum developed a $120 million campaign to build a 100,000-square-foot museum on Pier 39, in San Francisco, with a targeted opening date of 2008. The museum continued simultaneously to develop its global program, holding thirteen major exhibits focusing on such topics as women and political participation, global motherhood, and women’s role in the global economy.

In 2005, after the museum had invested nearly $1 million in site evaluation and raised cash and pledges of $7.5 million, site inspectors uncovered significant structural problems with the pier that would cost an additional $20 million to correct.4 The additional costs were too exorbitant, and the museum canceled its plans to build a physical museum and refocused on the original mission of running a “museum without walls.”

Partnership with the Global Fund for Women

That same year, IMOW began a relationship with GFW that would prove to be very fruitful for both organizations. With funding from a GFW grant, IMOW was able to produce a large-scale virtual exhibition, Imagining Ourselves: A Global Generation of Women. The exhibition included an intersection of film, photography, music, poetry, and personal essay—all responding to the question, “What defines your generation of women?”5 GFW promoted the exhibit to its stakeholders, allowing IMOW to tap into a much larger network and increase global exposure to the virtual exhibit. The result of their collaboration is an ongoing, interactive, multilingual exhibit that has thus far received over sixteen million visitors, and more than one million people representing 230 different countries have participated in producing content—personal stories dealing with war and peace, cultural conflict, motherhood, identity, and other experiences important to women globally.

The exhibit received worldwide attention and, in 2007, led to IMOW’s winning the Anita Borg Social Impact Award, which recognizes the accomplishments of women leading in technological innovation. As the institute expressed it at the time, “[IMOW] amplifies the voices of women worldwide through history, the arts and cultural programs and exhibits that educate, create dialogue, build community and inspire action. With its unique focus on cultural change, the Museum advances the human right to gender equity worldwide.”6 The success of the exhibition demonstrated to both entities the global impact that could be effected through strong partnership, and reinforced IMOW’s belief that a virtual museum was a relevant model for advancing its mission and engaging a global audience.

Financials

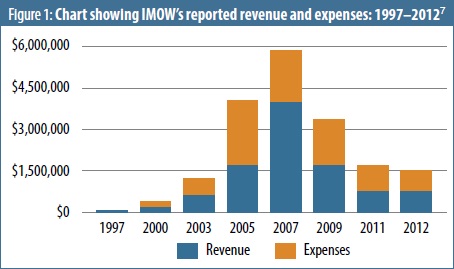

Just one year after the success of their exhibition and winning the Anita Borg Social Impact Award, however, IMOW’s financials began a downward spiral. A review of the museum’s Form 990s over the seventeen-year period of its filings, illustrated below (figure 1), tells the whole story.

While the museum was established as a 501(c)(3) in 1985, 1997 was the first year it was required to file a Form 990 with the IRS, at which time it reported zero expenses and a modest annual revenue of $31,890. By 2001, total revenue was at $641,658—a nearly 2,000 percent increase. Between 2003 and 2005, there was a large leap in expenses due to the undertaking of the capital campaign. Total expenses in 2005, the year IMOW announced the end of the campaign, came in at over $2.3 million, while total revenue was just under $1.6 million—a net loss of approximately $770,000.8 Between 2005 and 2011, expenses went down and revenue increased; and in 2007—the peak of its growth—IMOW brought in nearly $4 million in annual revenue, ending that fiscal year with a net gain of $2,116,579. The following year, however, revenue plummeted to $889,262, and the museum ended fiscal year 2008 with a net loss of more than $2 million. By 2013, the final year IMOW filed, it reported a total revenue of just $655,462—a dramatic decrease from just five years prior.

What was behind this downward spiral?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

During the capital campaign, IMOW had “staffed up” and brought on a vice president of development, further adding to its overhead expenses. This employee was given a comparatively outsized annual salary of $155,000 (as a comparison, the vice president of education management and the vice president of marketing were paid $55,000 each, annually). Furthermore, the executive director’s compensation rose from $22,000 to $177,000 during this period, significantly adding to IMOW’s increase in total expenses.9

As the money from the capital campaign began to disappear, IMOW’s overall financial situation plummeted further. While IMOW’s official explanation was that the needed repairs to the pier had caused the project’s demise,10 a look into IMOW’s records by San José State University indicates that the campaign “ultimately failed due to lack of funding and the economic downturn.”11 By 2008, IMOW was operating at a total net loss of more than $2 million. Of its expenses, $2,030,486 was paid toward program services, while it received a mere $856,141 in contributions. Furthermore, in 2008, the museum’s CEO was paid $208,981, and two other employees, the vice president of development and the vice president of programs, were each paid $120,000.12 While not outlandish figures for a large international organization, it is problematic for the salaries of staff to rise while an organization is operating at an extreme loss.

By 2010, clear structural changes had been put into effect: the CEO was replaced, and there were major reductions in salaries and paid positions. By 2012, IMOW’s total revenue was just $757,920, and expenses were $714,929. The new executive director was given an annual salary of $117,000, and there was only one other paid position.13 It is clear from these numbers that, even though IMOW was staying afloat, it did not have the assets or staff to make the global impact it desired.

The Merger

Meanwhile, in contrast to IMOW’s shrinking numbers, GFW was—and remains—a true powerhouse in women’s rights advocacy: its 2012 revenue was over $18 million with expenses just under $15 million.14 GFW invests nearly $9 million each year in women-led organizations.15 Its efforts have helped to form women’s rights organizations, launch Women’s Funds, and provide more than $100 million dollars in grants to over 4,600 organizations in 175 countries.16 GFW’s extensive community and strong financial stability were a clear lifeline to the struggling IMOW, and IMOW’s commendable skills in digital storytelling promised to help accelerate GFW’s communications efforts. IMOW and GFW saw the opportunity to double their impact, reach new audiences, and get closer to achieving their shared vision: “a just, equitable, and sustainable world in which women and girls have resources, voice, choice, and opportunities to realize their human rights”17—and in March 2014, the two organizations merged under GFW’s name.

IMOW has only released positive publicity regarding the merger, but it necessitated considerable sacrifice. Not only did IMOW as a legal entity disappear, it also gave up its independence and ability to control its decisions and future. GFW’s CEO and president, Musimbi Kanyoro, continues to serve as CEO, while IMOW’s president became vice president of advocacy and innovation. In addition, due to GFW’s much larger size, the boards of each organization did not merge equally—GFW’s board took on just two members of IMOW’s board.18

IMOW’s merger with GFW was a selfless and strategic move to achieve its stated goals. Simply put, by combining forces with GFW, IMOW could be most effective.

Moving Forward

According to the Stanford Social Innovation Review, nonprofit mergers and acquisitions have dramatically increased over recent years:19 “Merged nonprofits can roll together annual audits, combine insurance programs, and consolidate staffs and boards. But they are also bigger and more complex and require more and better management—a cost that often exceeds the savings from combined operations.”20 It has been just nine months since IMOW and GFW merged, and it appears that the merger was a successful move that relieved IMOW of its financial struggles and helped to further both organizations’ global impact. Still, it will be interesting to see whether this merger allows IMOW to continue its mission within the GFW infrastructure, or if IMOW will struggle with the loss of its own unique identity and sense of autonomy.

Notes

- “About [the International Museum of Women],” International Museum of Women, accessed October 30, 2014, www.imow.org/about/.

- Ibid.

- Rachel Miller, Danelle Moon, and Anke Voss, “Seventy- Five Years of International Women’s Collecting: Legacies, Successes, Obstacles, and New Directions,” American Archivist 74, no. 506 (2011): 18, www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/AAOSv074-Session506.pdf.

- Sarah Duxbury, “Women’s Museum Pulls the Plug on $120M Pier Plan,” San Francisco Business Times, April 21, 2005, www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/stories/2005/04/25/story3.html?page=all.

- “What Defines Your Generation of Women?,” Imagining Ourselves: A Global Generation of Women, International Museum of Women, accessed November 9, 2014, imaginingourselves.imow.org/pb/Home.aspx.

- “Paula Goldman: 2007 Social Impact ABIE Award Winner,” Anita Borg Institute, accessed November 9, 2014, anitaborg.org/uncategorized/paula-goldman/.

- Adapted by the authors from “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” International Museum of Women, 1997–2012.

- “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” International Museum of Women, 1997–2012, accessed November 1, 2014, www.guidestar.org/organizations/77-0072401/international-museum-women.aspx#forms-docs. See also www.guidestar.org/organizations/77-007240/international-museum-women.aspx#forms-docsg.

- “Paula Goldman: 2007 Social Impact ABIE Award Winner,” Anita Borg Institute.

- Duxbury, “Women’s Museum Pulls the Plug on $120M Pier Plan.”

- San José State University, Guide to the Women’s Heritage Museum/International Museum of Women Records, MSS-2010-02-1818 (San José, CA: San José State University Library Special Collections & Archives, 2010), 3.

- “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” International Museum of Women, 1997–2012.

- Ibid.

- “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” Global Fund for Women, 2012, accessed November 1, www.guidestar.org/organizations/77-0155782/global-fund-women.aspx#forms-docs.

- “Financial Highlights,” Global Fund for Women, accessed November 1, 2014, www.globalfundforwomen.org/who-we-are/financial-highlights.

- “25 Years of Impact,” Global Fund for Women, accessed November 1, 2014, www.globalfund forwomen.org/impact.

- “Merger FAQ,” Global Fund for Women, accessed October 30, 2014, www.globalfundforwomen.org/merger-faq.

- “Our Merger with Global Fund for Women,” International Museum of Women, accessed October 30, 2014, www.imow.org/about/merger.

- David La Piana, “Merging Wisely,” Stanford Social Innovation Review 8, no. 2 (Spring 2010).

- Ibid.

Global Fund for Women on the Strategic Drivers of the Historic Merger of Two Women’s Organizations

As the leaders of the two merging organizations, International Museum of Women (IMOW) and Global Fund for Women, we wanted to take the chance to respond and to highlight the strategic drivers, values, and practices that we believe are making our year-old merger a success. Nonprofit mergers are rarer than they should be, and we hope to encourage new conversations and ideas about this route.

There are several key factors that we believe have given our merger a promising start:

- Focus on strategic value. We knew that for a merger to be sustainable, the strategic value must be there. Our Boards’ joint vision was an organization that could bring together stronger voices (advocacy) and stronger resources (grant-making) for the world’s women. IMOW brought creative, multimedia, and digital storytelling expertise that had won recent funding and accolades from organizations ranging from Google and Wells Fargo to the U.S. State Department and the National Endowment of the Arts. Global Fund for Women had a 25-year history of grantmaking and a deep global network. We knew that joined together, this powerful combination could elicit exponentially higher returns for women’s human rights.

- Careful research and due diligence. We engaged in deep analysis and research that validated our hypothesis that the merger was a fit from both a mission and a fundraising perspective. We also spoke, explored, and negotiated for nearly two years before finalizing the merger—first together, and then with wider and more formal constellations of the staff and Board.

- Engagement from the Founders. As well as engagement from both Boards, we recognized we needed to harness the support and passion of both organizations’ founders. Elizabeth Colton, the founder of IMOW, was a visionary proponent of the merger, and her support was catalytic in engaging other supporters. Ann Firth Murray, a founder of the Global Fund, likewise got behind the plan and was the first to congratulate the combined staffs in our merger celebration in March 2014.

- Strong strategic involvement for IMOW People. We were conscious that IMOW’s staff and Board members needed visibility and strategic involvement—alongside Musimbi Kanyoro as the Global Fund for Women’s CEO—in order to bring the vision of the merger to reality. Roxane Divol, IMOW’s Board Chair, is now the Chair of Global Fund for Women’s Board Strategic Planning Committee and overseeing our new strategic plan that will launch later this year. Clare Winterton, IMOW’s former Executive Director, is now VP for Advocacy and Innovation. Immediately after the merger, she led a project with nonprofit consultants FSG to refine the organization’s identity and focus and she is playing a lead role in steering a rebranding of the organization.

- Finally, focus on the gain and not the “sacrifice.” In a merger, there is a lot of change. Everyone loses something and everyone gains something. When you are passionate about the mission—and nothing makes us more passionate than ensuring equality for every woman and girl around the world—the gain is bigger than the loss.

We know the world’s women need an organization that can champion them with a loud voice, with secure funding, and with credibility, influence, and reach. Our merger gets us closer to that goal.

Musimbi Kanyoro, CEO, Global Fund for Women

Clare Winterton, VP Advocacy & Innovation, Global Fund for Women