Editors’ note: This article is from the fall 2022 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “The Face of Climate Change.”

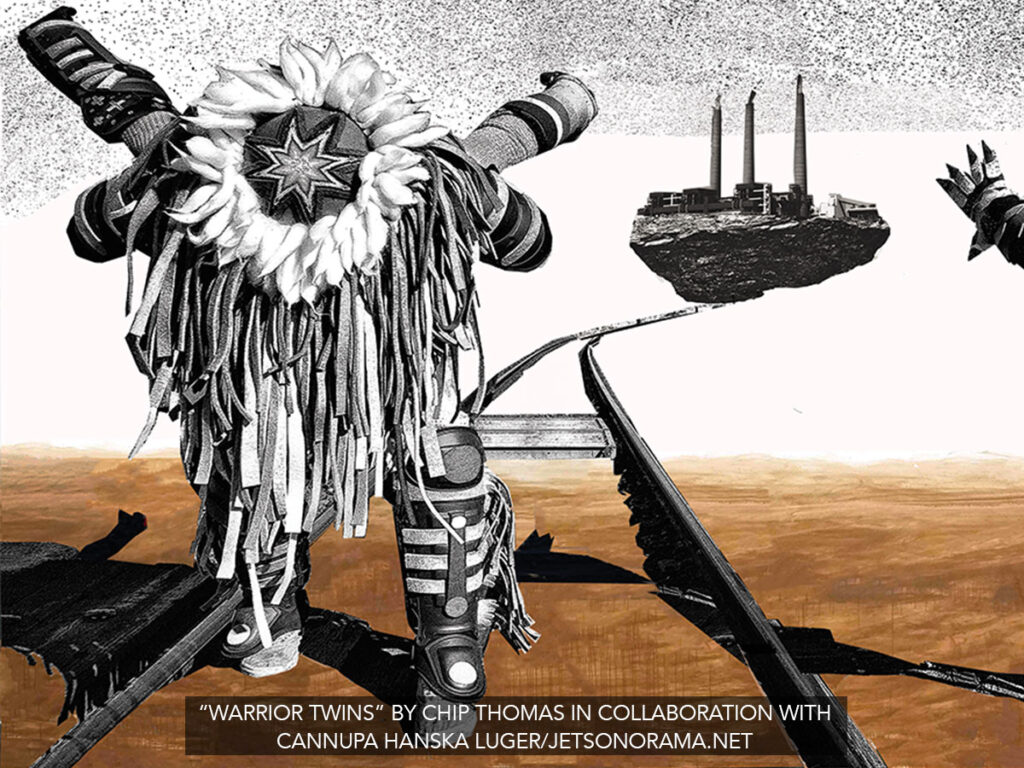

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

In my community, cycles are fundamental to understanding our world. Everything happens in cycles. From the growth of people, animals, and community, to the weather—cycles help define our relationships with all that surrounds us. Even the accumulation of knowledge happens in cycles.

Because of this understanding, four basic tenets of life are: (1) always be mindful of the fact that we are part of many cycles happening all around us at any given time; (2) everything living will return to repeat the cycle from which it started; (3) the end is just as important as the beginning; and (4) the middle of the cycle is always difficult to recognize, unless one is paying close attention. So, when climate change is described as an ending or apocalyptic human event—as it so often is, particularly in news and articles—I have to pause and return to my most basic teachings, and articulate the dramatic environmental and social changes in my lifetime as parts of a process that has neither a beginning nor an end but rather comprises events and markers of a recognizable cycle. The question then is, What is the cycle we are meant to recognize?

Climate change is as much a political marker as it is an environmental and social crisis. News stories daily announce a warming planet experiencing ongoing droughts, floods, wildfires, and endangerment or outright extinction of critical species of animals and plants. In the midst of this, corporations continue to make record profits, food prices rise, and in so many ways the world continues to operate in a “business as usual” way, albeit at a higher and higher cost that is unbearable for many. For some communities, the cost–benefit analysis of climate change is inherently distorted to begin with, while other communities bear the burden of climate change disproportionately—and have done so since its inception.

In a write-up of the International Panel on Climate Change’s most recent report, historian Harriet Mercer declares, “Connecting climate change to [. . .] acts of colonisation involves recognising that historic injustices are not consigned to history: their legacies are alive in the present.”1 Indeed, suppression of fire management and controlled burns, which is most readily used as an example of colonial disruption of Indigenous practices that are much needed presently, is but one of many other examples of colonial models that have led to environmental harms and climate crisis—first, and most critically, the removal of entire communities from their lands, either for colonial expansion or forced labor. This creates a process of devaluing, for the communities with the closest relationship to land know, understand, cultivate, and protect the value of the land on which they live and depend.

We can reteach ourselves to see and understand how to change long-standing detrimental behaviors, habits, and institutions that have altered our human ability to respond to injustice, damaged our sense of responsibility to one another and our environments, and blinded us to the paths of coexistence with our planet and each other.

The process of removing the people from the land means that the value, history, and relationships embedded in that human–land relationship are not only not communicated but completely disregarded. A new value can be assigned; however, the new value will be severed from the history, knowledge, and people—the very aspects of land value most desperately needed in order to understand climate cycles and human (and nonhuman) survival through these cycles. Also, once people have been forcibly removed from their lands a first time, subsequent removals become much easier; the behaviors, justifications, institutional permissions to remove entire groups of people from their land desensitizes society to loss in the name of “progress” and even “conservation.” The climate crisis, really, is waves of one loss after another.

Yet windows into change and opportunities to explore new models exist—especially when the communities can tell their own stories. It is in the experience of these communities that we recognize the need for climate justice—not just in recognition of the communities that are often ignored or minimized but also because it is in the stories and lessons of climate injustice that we can recognize the cycles, particularly the most destructive ones, that are accepted as a “norm.” We can reteach ourselves to see and understand how to change long-standing detrimental behaviors, habits, and institutions that have altered our human ability to respond to injustice, damaged our sense of responsibility to one another and our environments, and blinded us to the paths of coexistence with our planet and each other. We begin by listening to and offering voice to people and communities who have stories that are outside of that norm, outside of the typical newsreels that continually reinforce the detrimental cycles.

Dr. Dan Wildcat, a Yuchi member of the Muskogee Creek Nation and professor and director of the American Indian Studies program at the Haskell Indian Nations University, says, “When we speak of climate change, we also need to speak of cultural change.” Indigenous people’s stories are the embodiment of that cultural change. Recently, a friend shared with me a photo of a cross-section of a Redwood Tree recently fallen from old age near the Sequoia National Forest. He pointed out that the tree’s color began to change 500-plus years or so ago, around the time of European contact in that specific area, going from a deep red in pre-contact times to white post-contact. The almost instant color difference marked a dramatic shift in the tree’s environment, in our environment—and understanding what happened in that shift is critical information about the destructive cycles that began with European contact and critical information about how to change.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But, how do we “hear” the story? It is through the stories of the people who live and interact daily with that tree that gives access to the story of that tree. The Sequoia National Forest is now under the tutelage of the National Forest Service, but prior to that, Mono (Monache), Wuchumni, Tübatulabal, Paiute, and Western Shoshone occupied and stewarded the land, most likely when the tree still held its deep red color. The people’s removal from their homelands is a critical part of the story that is often ignored, minimized, or justified as a natural progression of agricultural civilization. But, is it? The change in color seems to tell a whole different story. The story of Indigenous peoples offers critical information to our present cycle formation, and we are all sorely disadvantaged when the Indigenous story is missing—as it has been for far too long in our American story. It’s time to change that.

This series captures some of the stories of Indigenous people and communities in their own words. These “cycle” stories offer insight, knowledge, and understanding through stories of climate change from the perspectives of people, animal, and plant relatives. The authors come from Indigenous communities spanning North America from the southwest to Alaska, and Peru. These insightful, witty, and deeply thoughtful people work daily with their communities, plant communities, and animal communities—and bear witness to the changes in their own landscapes and practices. But most important, they bear witness to the response of their communities to these changes.

A common thread weaves through all these stories: They are often not told or not heard. This is not the case because Indigenous people haven’t told their stories, but because the world has created a history where most Indigenous stories go unheard. While there are many reasons why such a dynamic has embedded itself in our American and other “western” institutions, there are many more reasons why that dynamic needs to be undone. Indigenous stories are fundamental to the cycle of climate, environment, and our human ability to adapt and prepare for the most trying parts of the cycle.

When we listen to Indigenous stories, we begin to recognize the beginnings of damaging behaviors that have led us into extractive processes that are rarely ever questioned: land accumulation at the expense of entire communities; replacement of slow growing plant relatives because there is no market for non-commodity crops; diversion of water from natural landscapes to only money-generating enterprises; deprivation of entire ecosystems of sustenance; devaluation of countless human and nonhuman communities for extraction of more valued resources; and replacing Indigenous knowledge systems for western ones, because it’s a marker of “civilization.” These behaviors and the institutions that support their continued practice have degraded our planet to a point of crisis.

Changing long-standing institutions and behaviors requires both individual and collective action. It means reforming the story of the present and who we, as a society, are. We can start with listening to the stories of those who are typically excluded in our national narratives—the Indigenous people who continue to live, thrive, witness, and care for the lands, communities, and nonhuman relatives who remain despite it all.

This series only touches on the vast Indigenous knowledge of the environment and how climate change is part of the knowledge, it is my hope that readers will become curious enough to learn more—and, more important, will begin to recognize the patterns of cycles that we continue to contribute to and desperately need to change. Indeed, each one of us can, instead, find ways to contribute to cycles that sustain us all.

Notes

- Harriet Mercer, “Colonialism: why leading climate scientists have finally acknowledged its link with climate change,” April 22, 2022, The Conversation, theconversation.com/colonialism-why-leading-climate-scientists-have-finally-acknowledged-its-link-with-climate-change-181642.2. Articulated during an informal gathering at which the author was present.

- Articulated during an informal gathering at which the author was present.