April 15, 2020; Arizona Horizon and KPNX 12 News

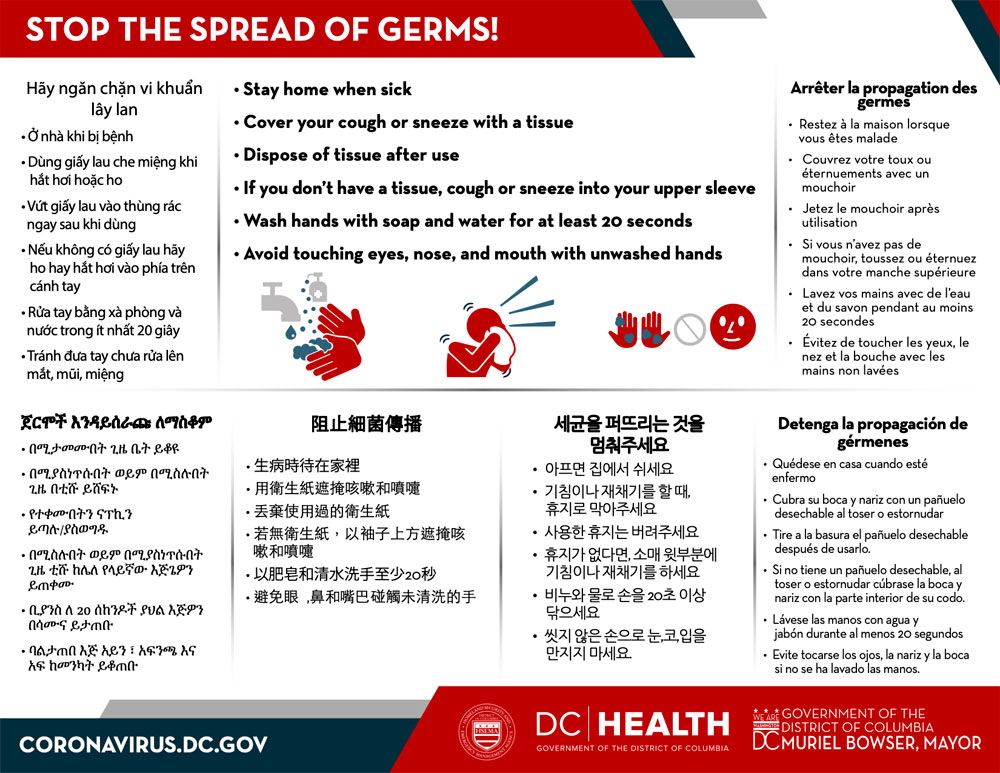

Much of the information about COVID-19 and its spread and suppression arrives via television, online news, and radio—almost always in English or Spanish. So how do refugees, immigrants, and indigenous populations who speak other languages receive the guidance they need to protect themselves during the pandemic?

In Phoenix, Dr. Michael Do of Valleywise Health’s refugee clinic worked with the clinic’s cultural health navigators and the Arizona Refugee Resettlement Program to produce videos about COVID-19 in ten languages including Arabic, Burmese, Kirundi, and Swahili. His motivation was to provide accurate information about the virus in languages that respected the identities and cultures of the clinic’s diverse patient population. Video was chosen to circumvent literacy challenges inherent in handouts and other print materials.

Do, the clinic’s lead pediatrician, told KPNX 12 News that limited access to health information is “compounded even more within our refugee families due to the language barriers, the cultural barriers that they face. Not to mention many of our refugee families have large families with multiple generations, many children, and in a pandemic in which the infection is spread from person-to-person, this poses a larger risk.”

Early data from Kaiser Family Foundation suggests communities of color will face increased health and economic risks from COVID-19. These communities are often hit hardest during health crises of this nature; a report from Texas Health Institute on the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic found that “disparities in morbidity, hospitalization, and mortality were driven by socio-cultural and economic factors which lead to increased H1N1 exposure, greater H1N1 susceptibility, and delayed H1N1 treatment among racial and ethnic minorities.” The report also mentions how language barriers and cultural preferences in communications likely limited the understanding and implementation of physical distancing recommendations at the time.

It’s no surprise, then, that refugee, immigrant, and indigenous communities are especially susceptible to widespread contraction of COVID-19. That’s why Do’s native-language video project, along with similar translation and communication efforts from Harvard Medical School in Boston and the Natividad Foundation and Natividad Medical Center in Salinas, California, are so crucial to both slowing the coronavirus and protecting the health and well-being of these groups.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Vox notes that local health clinics are often seen as trusted sources by the communities they serve and that physicians are using inspired tactics to share information about the pandemic. The Academy of Medical and Public Health Services is using WeChat, an app popular with Chinese immigrants, to translate government responses into Mandarin in New York City. In Cleveland, Dr. Assim AlAbdulKader calls patients who’ve tested positive for COVID-19 to explain the nuances of quarantine and isolation in Arabic.

“I’m trying to support and empower them to take ownership of health but also to be firm, because we know that isolating and quarantining aren’t options, they are important,” AlAbdulKader said when explaining how he balances Western approaches to medicine with the health expectations of Middle Eastern and Asian populations.

Beyond language and cultural barriers, there are additional obstacles. NPQ has reported on the Trump administration’s harmful public charge rule, undocumented immigrants’ lack of resources and glaring omission from the CARES Act, and the exploitation of farmworkers, many undocumented, now deemed essential by the government. These realities are not helping impede the virus’ spread.

Refugee, immigrant, and indigenous communities’ limited access to reliable health information, reinforced by racist and/or nativist policy, are additional cogs in a machine designed to reinforce inequitable systems. But physicians like Do and AlAbdulKader are doing what they can to help their patients with respect to deeply significant cultural identities, practices, and languages. It’s another excellent example of the community-based supports NPQ had been documenting throughout the pandemic—from mutual aid mask making to creative self-expression during isolation—and a heartening reminder that we can often depend on each other when systems fail.

Speaking with Arizona Horizon, Do says, “So many of our families are thankful—and I’ve heard this message over and over—they’re thankful because they haven’t had access to materials in their languages, things that they could understand.”

He continued, “To have such videos showcasing members of the respective refugee communities…has been a really great effort and really well received by the communities at large.”—Drew Adams