This article is being co-published by NPQ and Shelterforce, the longtime community development publication of the National Housing Institute.

How is value created in the economy? Clearly, there are many factors; the allocation of financial capital is one, but value creation also involves testing new business ideas (arguably, the true meaning of the term “entrepreneurship”), a skilled labor force (which speaks to the importance of education, workforce development, and training), the presence of other firms (suppliers and the like), a means to deliver goods and services to customers (which speaks to the value of infrastructure such as transportation, broadband, power, water, sanitation, and so on), access to land, the proximity of major universities (it’s no accident that Silicon Valley is near Stanford), and internal controls (the visible hand of management, in the late Alfred Chandler’s famed analysis).

In some cases, tax breaks can help build economic value. For instance, with research and development, the tax break serves as a kind of public matching capital for private investment, even if the public typically receives no return except through later tax revenues. Similarly, tax breaks can encourage the reallocation of capital to new industries that have broad benefits (e.g., renewable energy). But using tax breaks simply to entice a large firm to locate in one city or state over another doesn’t really do anything to create new economic value.

And yet today we have an entire industry which delivers what are euphemistically called “economic development incentives.” In California, for example, the Fresno County Economic Development Corporation notes that they will “customize an incentive calculation to provide clients with an accurate monetary amount they can potentially receive if their companies take advantage of the programs available.” I chose Fresno, but I could have chosen almost any US city. The strangeness of this practice is hidden by its ubiquity. Here you have a quasi-governmental body—it should be noted that, often, as in Fresno, these bodies are, formally speaking, incorporated as nonprofits—advising taxpayers how to pay less for public services.

A report from the nonprofit Brookings Institution notes that cost estimates of economic incentives range from $45 billion to $90 billion a year, depending on the definition. A New York Times estimate from 2012, for instance, settled on the figure of $80 billion.

Presumably the larger numbers may include business-specific infrastructure expenses, while the small number refers more narrowly to direct tax abatements. While the benefits of infrastructure expenditures, depending on what they are, may extend beyond the business in question, the direct tax breaks are a near total loss. Public services, of course, are affected.

Because recent advocacy has succeeded in achieving a change in government accounting standards that led many cities and states to disclose the total costs of the tax abatements they provided last year for the very first time, we now are gaining a better sense of just how much these abatements take away from education and other public services. For example, a December 2018 study from the nonprofit advocacy group Good Jobs First based on newly released government tax abatement expenditure data that focused on public schools found that as a result of direct corporate tax abatements:

- School districts in just 10 states—South Carolina, New York, Louisiana, Ohio, Oregon, Michigan, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Georgia—collectively lost nearly $1.6 billion;

- Three of the five most-affected school districts are in Louisiana parishes. Together, they were shortchanged more than $158 million—more than $2,500 for each enrolled student;

- Two hundred and forty-eight (248) school districts in 22 states each lost more than $1 million in revenue; and,

- If abatements were curtailed and the resulting tax revenues were reinvested to hire additional teachers (at each state’s average teacher salary rate), the ten most-affected states could hire a total of 27,798 more teachers. South Carolina alone could hire more than 6,300 teachers.

Of course, proponents might claim these incentives drive future tax revenues. But research provides, at best, limited support for this proposition. A 2018 study by Timothy Bartik, senior economist at the Upjohn Institute, found that, “only 10–15 percent of the new jobs companies create in incentive-offering cities and states can really be credited to the incentives they offer.”

Peter Fisher, a retired professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Iowa and research director at the Iowa Policy Project, noted years ago that, “State and local taxes on businesses (corporate income taxes, sales taxes, local property taxes) represent only about 1.8 percent of total business costs on average for all states.” Fisher arrived at this figure by analyzing aggregated business deductions as listed on Internal Revenue Service corporate income tax forms.

Where do the other 98.2 percent of costs lie? The answer is obvious—in the everyday costs of doing business. As Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good Jobs First, points out, the main factors behind business location decisions are “business basics such as labor, occupancy, and other business inputs.”

Recently, Amazon’s second headquarters or “HQ2” free-for-all put on prominent display some of the absurdities of the economic development incentive game. A total of 238 communities responded to an eight-page, request-for-proposals document that managed to use the word “incentive” 21 times. At times, the extremes to which public officials went to promote their bids became laughable. As NPQ observed, “Yes, the mayor of Washington, DC, really did engage in a faux conversation with Amazon’s voice recognition software Alexa in an effort to cajole the company into selecting her city for its second headquarters. Tucson…sent a 21-foot-tall saguaro cactus on a flatbed truck to Amazon in Seattle.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

When Amazon cut its list of 238 cities to 20, LeRoy pretty much nailed it when identifying the actual drivers of Amazon’s investment decision. As LeRoy put it, “In this case, as in any large corporate headquarters siting, the key variable is the executive talent pool. For any company contemplating hiring 50,000 executives, the presence of other companies’ headquarters staff, along with strong university graduate programs in fields such as engineering, finance, law, and marketing will be the most important issue.” But, LeRoy added, the fact that the location decision would have relatively little to do with incentives does not mean that Amazon would refuse the incentives its already (confidentially) selected community might offer. After all, it’s profit, so, why not?

Of course, Amazon ultimately selected New York City and Washington, DC as dual second-headquarters cities, then pulled out of New York when community groups were, shall we say, less than enthusiastic to have “won” the location sweepstakes. And if you think economic incentives were decisive, then you have to ask why Amazon turned down $9.7 billion from Pittsburgh in favor of less than $2 billion from northern Virginia. Also, even Pittsburgh, at $9.7 billion was not the high bidder, as Dallas-Fort Worth international airport reportedly offered an astonishing $22.7 billion for Amazon to locate nearby. But Amazon, of course, turned this down.

Amazon, by the way, is hardly the worst offender. Provided Amazon actually produces the promised 25,000 jobs in northern Virginia, its incentive haul, even including infrastructure spent on its behalf, will amount to less than $100,000 per job. Given that the less sexy strategy of converting small businesses with retiring business owners into employee-owned companies has been shown to retain jobs at a cost of under $1,000 a job, this is not a bargain, but it is still well below the average “mega-deal” price tag of $658,000 per job.

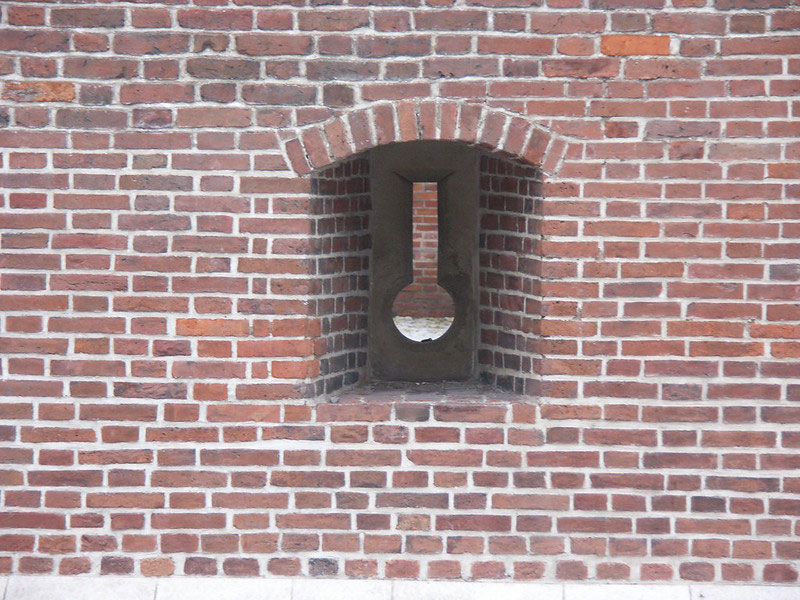

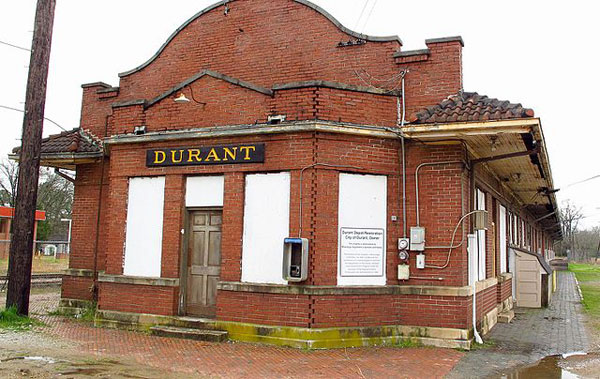

How did we get here? Two decades ago, Donald Barlett and James Steele wrote in Time about Durant, Mississippi, back in the Depression year of 1936. “The idea,” they explained, “was simple enough: lure businesses from the North with offers of cheap and abundant nonunion labor, low-priced land, minimal taxes and, for the first time, state-sponsored, tax-exempt industrial-revenue bonds. In other words, a coordinated effort to raid other states for their corporations.”

Barlett and Steele go on to write that:

The town of Durant (pop. 2,500), a farming community with more sidewalks than paved streets, was offering to issue $25,000 in industrial-revenue bonds to buy land and erect a 15,000-square-foot building, which it would lease to Real Silk for 25 years for all of $5 a year. In addition, Durant would waive five years of county taxes on the building and property taxes on the machinery. On top of that, the city would provide insurance, set up a training school and even erect housing for workers. In a front-page editorial that sounds eerily familiar, the Durant News crowed that the project was a great deal for the town. In a special election, the town’s voters approved the bond issue, 330 to 19. The people of Durant were in the hosiery business.

As for the rest of the story…well, by the mid-1950s, “Before the first bond was due to be paid off, Real Silk shut all its factories, including Durant, sold off the equipment, and became an investment company.” Barlett and Steele added that in terms economic development—you know, the reason for the incentives—Mississippi ranked last among US states in per capita income in 1936. And, in 1998, after six decades of economic development incentives, it still ranked last. Alas, the same remains true as of 2017, according to Federal Reserve data.

Today, it appears that Mississippi might, finally, be focusing more on business fundamentals. Recently, NPQ covered growing community-based economic development efforts in the state. Also, earlier this year, the state moved in impressive fashion to invest in broadband. Of course, as the Amazon scrum illustrates, economic development incentives are pretty universal these days—prominent in economic development departments of cities, counties, and states—whether wealthy or poor. Policy could help rein these practices in. Last month, Good Jobs First outlined some options. Among these are:

- State ceasefire pacts to stop paying corporations to relocate short term distances across state lines (such as from Kansas City, Kansas to Kansas City, Missouri and back again).

- Subsidy caps which could be, “per project, per job, per program, and/or per company” or even as a percentage of a government’s tax base.

- Advance notice so the public can weigh in on deal costs and benefits.

Good Jobs First also advocates rules at the federal level, akin to those that the European Union (EU) has employed for years. In the EU, Regional Aid Guidelines cap “aid intensity” (the amount of subsidy divided by the amount of private capital investment made). As Thomas Cafcas and LeRoy explain, this effectively limits the use of economic development incentives so as to “allow larger [economic incentive] packages only in poorer areas.”

Then again, while policy that puts the brakes on “beggar thy neighbor” strategies would help a lot, even absent such policies, economic development agencies could choose to shift their focus from business attraction to policies that are true to their name of economic development—that is, to develop their local economies by investing in homegrown assets and employers. This is the path recommended by Bartik, by Richard Florida of the University of Toronto, as well as by Joseph Parillo and Sifan Liu, writing for Brookings.

Increasingly, communities are taking this message to heart. For example, in 2017, Buncombe County (county seat Asheville) in North Carolina, “voted to remove $1.5 million from the county’s $5 million economic development incentive pool to finance a small business loan program and expand preschool education.” This year, in Plattsburgh, New York, the Adirondack North Country Association (ANCA), launched the North Country Center for Businesses in Transition to stabilize local small business by supporting business succession, as part of a larger strategic approach based on “self-reliance for goods and services through locally owned” businesses. This year too, in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a local school board made national news when it turned down a tax abatement request from ExxonMobil. And in New Jersey, the state is currently conducting a review of its economic incentive programs.

In short, a shift in practice may be emerging—and the recent activism against the Amazon tax incentive deals in New York City, Arlington, and Nashville provides at least cautious reason for optimism. That said, the current system of economic development incentives and tax abatements was not built in a day. While economic development may be starting to focus more on building the assets of the local community, there is still a long way to go.