August 14, 2016; Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “myAJC”

When trying to solve difficult problems, one would think knowledge and facts would be important to politicians, policymakers, and funders. When it comes to the ongoing national effort to strengthen public education, though, it seems knowledge is much less important than political philosophy. And nowhere is that so evident as when we consider the impact of poverty on the lives of children and families.

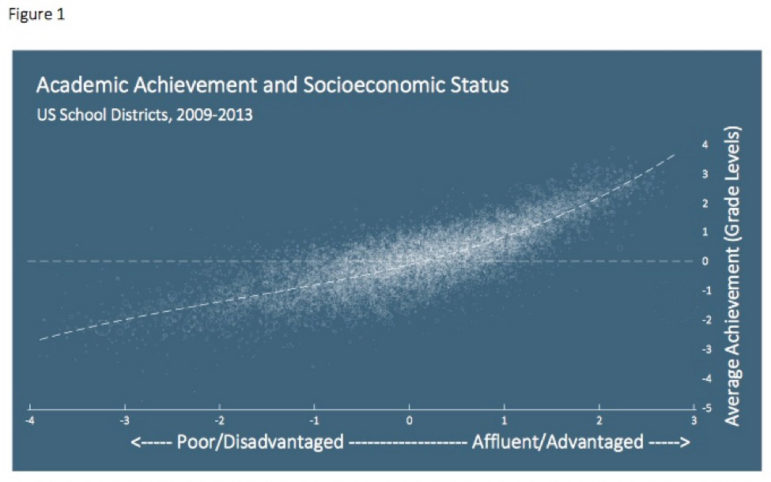

There is no question that poor children are falling behind their more affluent peers. A recent study published by Sean F. Reardon of Stanford University again confirmed that poverty and educational performance are strongly connected. He found a “very strong, relationship between district socioeconomic status and average academic achievement.”

Students in many of the most advantaged school districts have test scores that are more than four grade levels above those of students in the most disadvantaged districts. The socioeconomic context of a school district is a very powerful predictor of students’ academic performance.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

To make this picture even starker, we are learning the difference between poverty and poverty. We now know that children who experience more extreme and persistent poverty do worse than peers whose exposure to poverty is more short term. Susan Dynarksi and Katherine Michelmore, University of Michigan, have studied these differences.

Those who first become poor by the time they enter kindergarten are least likely to escape poverty compared to their counterparts who become poor in later grades. They likely face a whole host of other issues such as unstable housing, family instability, and parental job loss. They also score significantly lower on standardized tests than both their counterparts who were never poor as well as their peers who were transitorily poor throughout grade school. Previous research linking test scores to adult outcomes suggests that these children are also less likely to attend college and earn lower wages in adulthood, which could have important implications for the intergenerational transmission of poverty and income inequality for years to come.

Despite billions of dollars of investment in “school reform,” the achievement gap is about 40 percent greater now than it was 25 years ago. Yet the solutions we are implementing and those being debated still focus almost universally on what will occur in classrooms and school buildings, factors that may influence less than half of a student’s success. In the words of researcher Dan Goldhaber, “The vast majority (about 60 percent) of the differences in student test scores are explained by individual and family background characteristics.” We focus on teachers and teacher unions, on testing, on the Common Core, and on disciplinary policies and ignore a much larger issue: poverty. Schools can and should get better; teachers can and should get better. We should be learning from schools where poor children are beating these odds and seeing if there are strategies that ought to be replicated.

But we cannot ignore poverty. Underlying much of the push to reform public education is the belief that the force of an open educational market place will drive struggling students to schools that will teach them better and drive failing schools to up their game and provide a better educational offering. But evidence suggests that that poor children face obstacles that keep them from learning as well as their more affluent peers despite the best efforts of the schools. Are we, in advocating for market-based solutions, just blaming the victims of a broader societal problem?—Martin Levine