August 17, 2020; The Economist and FiveThirtyEight

Back in late June, 500 political and civil world leaders and organizations signed a letter, “A Call to Defend Democracy,” alerting us that the coronavirus pandemic was being utilized by legitimate and illegitimate governments to undermine and threaten democracy:

Authoritarian regimes, not surprisingly, are using the crisis to silence critics and tighten their political grip. But even some democratically elected governments are fighting the pandemic by amassing emergency powers that restrict human rights and enhance state surveillance without regard to legal constraints, parliamentary oversight, or timeframes for the restoration of constitutional order. Parliaments are being sidelined, journalists are being arrested and harassed, minorities are being scapegoated, and the most vulnerable sectors of the population face alarming new dangers as the economic lockdowns ravage the very fabric of societies everywhere.

Today, one of the leading institutions making that call, the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, is keeping track of how elections around the world are being postponed under the justification of COVID-19. As of August 25, 2020, the Foundation recorded postponements in 65 countries and eight territories.

In Bolivia, for example, national elections have been postponed twice. The interim unelected president, Jeanine Áñez, used the pandemic to push elections from May to September, and then again to October 18. Advocates organized strikes and street blockades for weeks to protest both this decision and ongoing abuses from an illegitimate government that replaced Evo Morales after a coup in November 2019. An estimated 500,000 people occupied the streets of El Alto alone.

A self-described right-wing Christian, Áñez took power with a bible in her hand, despite the fact that Congress was not fully in session and Morales’s party MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo) had boycotted the affair. Her government has used the pandemic to persecute and jail the opposition and suppress freedom of speech, according to Amnesty International, by labeling the opposition as “terrorists” and “radical socialists” and anyone on news and social media critical of the administration as “destabilization and disinformation movements.”

Áñez’s administration declared a curfew and state of emergency at the onset of the pandemic and has sought to use her interim term to undo everything that Morales’s government enacted as Bolivia’s first indigenous president.

“Her response to the virus is politically relevant only because of her controversial decision to run in the election, months after she promised she would not. Polls indicate that Áñez has no shot of winning,” writes Assistant Professor Gabriel Hetland for the New York Times.

Bolivia is but one example that feels so distant to our reality and yet, so familiar.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

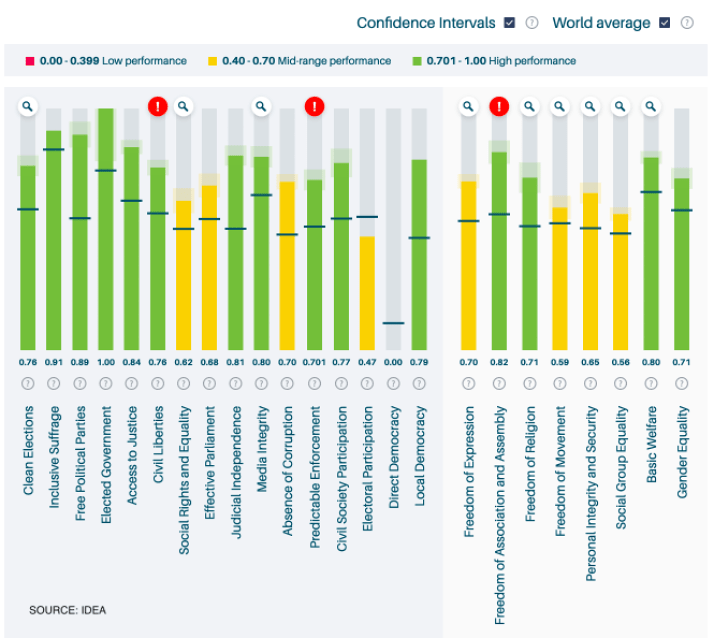

The Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, a think tank based in Sweden, runs “democracy indices” for every country. It has issued several alerts on the US based on a state of emergency declared back in March 20, with no end date. It also included Trump’s tweet in July floating the idea of postponing November’s presidential election, repeated disingenuous claims that mail-in voting will promote fraud, as well as manipulation of COVID-19 information for political means, as clear signs of a “non-impartial administration” and foreseeable human rights violations. Indicators on US civil liberties, freedom of assembly, and direct democracy also received low marks.

In “Call to Defend Democracy,” experts outline immediate steps to defend democracy, such as inclusive participation and dialogue, and issue warnings that the pandemic provides a perfect breeding ground for undemocratic encroachment:

Democracy does not guarantee competent leadership and effective governance. While democracies predominate among the countries that have acted most effectively to contain the virus, other democracies have functioned poorly in responding to the pandemic and have paid a very high price in human life and economic security. Democracies that perform poorly further weaken society and create openings for authoritarians.

[…]

The current pandemic represents a formidable global challenge to democracy. Authoritarians around the world see the COVID-19 crisis as a new political battleground in their fight to stigmatize democracy as feeble and reverse its dramatic gains of the past few decades. Democracy is under threat, and people who care about it must summon the will, the discipline, and the solidarity to defend it. At stake are the freedom, health, and dignity of people everywhere.

If you see any parallels with the current state of democracy in the United States, it’s because they are all there. Authoritarian governments, unfortunately, have much in common, and it always begins with the erosion of democratic institutions, information manipulation, and the misuse and abuse of federal powers.

Although a suspension of the US presidential elections is very unlikely, we should be just as worried if the executive were to suspend or contest, for example, state elections or voting results. Fortunately, if anything, primary elections during the pandemic across the US have been so far indicators that democracy advocates and leaders are indeed thinking ahead and attempting to guarantee safe and secure voting. In Wisconsin, for example, 75 percent of voters cast absentee ballots in April despite voting barriers. Indeed, all efforts to protect democracy will be crucial before and after November’s election.—Sofia Jarrin-Thomas