In his new book Evicted, Matthew Desmond recounts his experience living with and studying low-income families in Milwaukee. Desmond, the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences and co-director of the Justice and Poverty Project at Harvard, spent more than five years in the field. Now, just days since the “official” publication of book, Desmond has been lionized in the press and journals. Jason DeParle, writing in the New York Review of Books, says, “Desmond, a Harvard sociologist, cites plenty of statistics but it’s his ethnographic gift that lends the work such force. He’s one of a rare academic breed: a poverty expert who engages with the poor.”

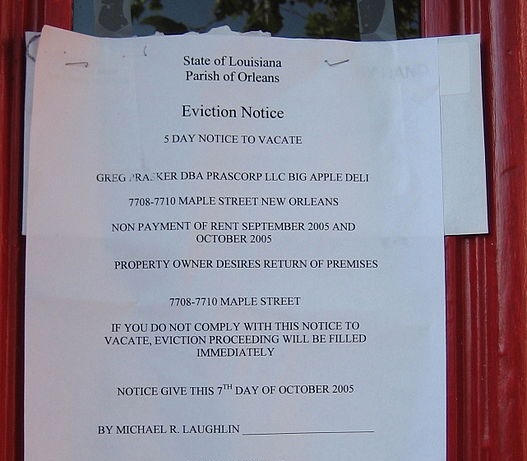

In Desmond’s work, eviction is the central reality in a system of rental housing instability that consumes the lives of the low-income families he studied. Eviction is both a literal loss of a home and a metaphorical separation of families from the economic mainstream of the U.S., a form of secular ostracism. In the first 24 chapters, Desmond describes the intricate dance of landlords, tenants, and civil authorities. He shines a light on practices like contingent eviction/forbearance techniques that keep tenants “in limbo” under the cloud of immediate dispossession. He describes the push and pull of making repairs, keeping rents affordable, and making a profit. Following these woven personal stories, Desmond offers an epilogue, a review of his methodology and an extensive and well-annotated “Notes” section.

In his epilogue, “Home and Hope,” Desmond connects the dots of the narratives: “The home is the center of life. It is a refuge from the grind of work, the pressure of school, and the menace of the streets. We say that at home we can ‘be ourselves.’” Then, he identifies the specific personal and social benefits that are derived from a stable home. Desmond makes the point that for years low-income tenants were able to find and keep stable rental housing for a reasonable 30 percent of income, but that, for the last two decades, rent inflation and wage stagnation has made affordability impossible. Desmond is not so technical in his analysis. He calls the root cause “greed.” In identifying solutions, Desmond calls for making housing stability a national priority and cites the need for a Universal Voucher Program with fair housing protections for voucher holders and expansion of legal representation for tenants in eviction court

In many ways, Desmond’s study is a throw back to a narrative, anecdotal research style based on participant observation. He’s in good company with a host of pioneering documentarians, including Jacob Riis, James Agee and Walker Evans, Michael Harrington and Lee Rainwater. All these writers come from a tradition of social documentation that is action oriented. In “From the Depths,” Robert H. Bremner wrote of the 20th Century Progressives: “Nearly all of these reforms involved limitations on private property rights and extension of public authority into areas previously regarded as the exclusive preserve of individual initiative.” What a shocking contrast to the “free market” reforms proposed by Speaker Paul Ryan in his campaign to remove the shackles of government programs from the poor.

Government is a player; landlords have professionalized

While there is no denying that evictions have skyrocketed in recent decades as incomes have failed to keep pace with rent, eviction is not a new phenomenon. Two other factors for the longer term increase in evictions: the shift from informal/self-help dispossessions to judicial evictions and the “professionalization” of property owners.

Jared N. Day’s book Urban Castles documents the emergence of a politically active real estate/landlord lobby in New York City that emerged in response to organized tenant actions to curb abuses in tenement housing. The evolution towards landlord “professionalism” came in two stages: first as a movement by real estate interests in the 1930s–1950s, and later as a movement by “mom and pop” owners who formed a different interest lobby around the notion of “investor associations.” In fact, Desmond calls attention to the emergence of the investors association in his narrative about “mom and pop” owners, Sherrena and Quentin Tarver. Even more recently, NPQ revealed how California’s Landlord Association teamed up with a local United Way to block rental reform.

As civil authorities took more and more control over the eviction process, landlords adapted to the new systems. With a combination of political influence on judges and legal representation in the courts, the emerging real estate/landlord associations shaped the eviction courts to their needs. In many localities, supported by the same political forces, local government or courts provide educational services to landlords. More recently, jurisdictions are using “nuisance” laws to promote non-judicial dispossession of “undesirable” tenants. Tenants, by contrast, lost their interest in and capacity to have a political influence on the courts and local government. Part of that loss was the institutionalization of the union movement after the 1940s and the cooling of the Civil Rights and Poor People movements of the 1960s.

Another development to which Desmond makes passing reference is the expansion of the landlord support industry. With the development of the information economy, data brokers have made it easier than ever for even the smallest landlords to know everything about everyone. Where once a local “blacklist” kept renters out of quality housing, now, like at “Cheers,” everybody knows your name…and where you lived and worked, and if you did time. Last month, Bloomberg News featured a story about businesses that provide eviction services to landlords using an automated protocol and custom documents and forms. The article makes this defense for automating the practice: “The first court filing is often just a bargaining tactic: In Baltimore, eviction cases are more likely to be settled than heard by a judge; fewer than five percent lead to the removal of a tenant.” Using the court as a collection agency is the goal.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A critical, yet easy to overlook part of Desmond’s analysis is the role of civil authorities in the eviction industry:

It is the government that legitimizes and defends landlords’ right to charge as much as they want; that subsidized the construction of high-end apartments, bidding up rents and leaving the poor with even fewer options; that pays landlords when a family cannot, through onetime or ongoing housing assistance; that forcibly removes a family at the landlords’ request by dispatching armed law enforcement officers; and that records and publicizes evictions, as a service to landlords and debt collection agencies.

The reason this insight is critical is that reform efforts do not need to focus on changing either landlord or tenant behaviors, but civil laws and procedures. Once trapped in the unsubsidized private housing market, the households described in Desmond’s study are condemned to the intricate dance of landlord, tenant, and civil authorities, where the deck is stacked against success. Desmond says, “Families forced out of their homes are pushed into undesirable parts of the city, moving from poor neighborhoods into even poorer ones; from crime-filled areas into more dangerous ones.”

Where from here?

There’s some reason to believe that Desmond’s book could catalyze an eviction reform movement. The key, as in the reform efforts of the Progressive Era of the 20th Century, is his recognition of the social costs of rental instability. Desmond and others have noted, among the social impacts,

- Stress-related diseases, including depression, suicide and interpersonal violence;

- Environmental diseases like asthma, lead poisoning, and mold-related infections;

- Low school achievement and employment opportunity;

- Neighborhood deterioration and the cost of code enforcement and blight removal; and

- Health and social service costs for housing the homeless, home search services, relocation, remedial schooling and social and criminal justice enforcement.

To these personal and social costs, one might add the 2004–2007 housing bubble, which was fueled in part by tenants seeking to escape the instability of rental housing. Many households fell for unaffordable homeownership schemes with the hope of escape from an inherently unstable system, only to be faced with foreclosure, broken credit, and a return to the same system when the bubble burst.

Here’s where Desmond’s analysis of potential solutions falls a little short. His recommendations for a universal voucher program are Sanders-esque in its scope, even though I recommended this myself in NPQ some months ago. Luckily, there are some ways to start down the path of reforming the eviction and rebalancing the scales of justice between landlords and tenants that don’t require big new federal programs. Desmond’s other recommendation is to provide legal representation to everyone in eviction court. This simple and relatively inexpensive initiative could rebalance the scales of justice. As Desmond notes, “Due process has been replaced by mere process: pushing cases through. Tenant lawyers would change that.” Right now, the Right to Counsel Coalition of NYC is fighting to expand upon the pilot projects mentioned in Desmond’s book.

Court reform could be as simple as a change in procedures to encourage pre-filing or per-judgment mediation between tenants and landlords. Similarly, a provision in state law to implement “pay to stay” protections for tenants would permit more time to redeem a late payment situation. Pennsylvania has such provisions and has not become a haven for “rent-beats.” Right now, citizens in Baltimore are headed for the state capital to demand legislation to reform the Baltimore Rent Court (advisory: auto-play audio), which was once a bastion of reform but became captured by the real estate and landlord interests and has become a publicly funded collection agency for these property interests.

Another cost-free provision that would dramatically change the balance of power between landlords and tenants would be the extension of “just cause” terminations to all rental agreements. Again, this is a well-tested idea, since “just cause” is a component of leases in federally assisted housing, Low Income Tax Credit Housing, and in cities with rent control ordinances. The idea behind “just cause” protection is that a tenant can only be evicted because the tenant violated the rental agreement. In other words, as long as the tenant pays rent and lives by the rules, she or he can stay in the home. Citizens in Oakland and Boston are mounting active “just cause” campaigns right now.

The really nice thing about a social impact approach to court reform is that advocates can pull in two interest groups that are currently not part of the housing reform movement: health and social providers and middle class tenants who are one paycheck away from being dispossessed. For health and social service providers the attraction of rental stability is obvious: Stable homes reduce health and social impacts of the current system. For middle-class tenants, the prospect of not losing a home because of an auto accident, unexpected layoff, or medical bill could make this an attractive movement to support. In fact, with the growing number of middle-class renters who have some history of political participation (voting, calling, writing and funding), they could become a potent force for change that benefits all tenants.

For the moment there are two missing ingredients to eviction reform: public awareness and local leadership. Desmond’s book could start filling the public awareness gap. He’s everywhere with his message of the need for change. Local leadership is trickier. Housing advocates are so accustomed to talking to each other that they have lost the knack of talking to real decision-makers, most of whom have no recent experience of being renters and who depend on financial support from the property-based industries. Still, when the winds of change are blowing…it’s time to open all the windows.