November 27, 2017; CityLab

“Cities are right to pour their energy into homegrown businesses,” advises David Zipper, who served as director of business development for Washington, D.C. from 2009 to 2013 and now is a fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

Zipper is no wild-eyed local economy enthusiast. Indeed, he warns cities against issuing high-risk “large contracts to local startups for untested or inferior products.” But, as Zipper outlines in CityLab, cities adopting a “grow-your-own” orientation to economic development can draw on a wide number of lower risk economic development tools that they have at their disposal.

As Zipper writes,

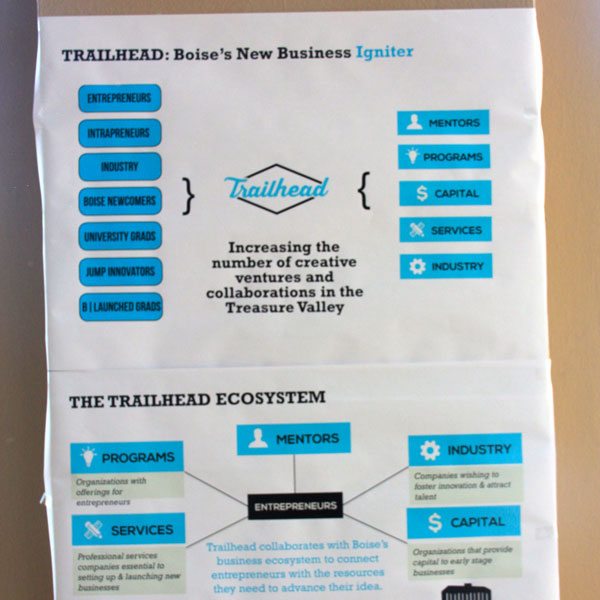

There are plenty of ways for city leaders to support startup-fueled economic development without dipping into public coffers. An easy process for business licensing and registration can nudge prospective entrepreneurs to take the plunge (and make life a little easier for existing businesses, too). Creating a startup advocate position within city hall—as Seattle has done—can give founders a useful “front door” when they have questions about setting up shop or navigating city government. Cities can also provide funding and support to create a startup hub that brings together students, entrepreneurs, investors, and corporations—much as Boise did when Trailhead launched in 2015. Each of these techniques can improve the urban environment for startups and make it easier for new ventures to launch and scale.

The nonprofit Trailhead acts both as a hub and accelerator for local small businesses. It presently has about 375 individual members and supports more than 60 member companies. Similar organizations can be found in other cities. For example, in Richmond, Virginia, a city-business partnership known as RVA Works acts in a similar fashion.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

City officials can also use the bully pulpit to good effect. For instance, Zipper writes,

A mayor could visit a startup’s office or tweet about their product. A testimonial from a city official can be a powerful lift to an entrepreneur building a brand and show legitimacy to prospective customers. A mayor could also deploy her network to help a local startup, providing connections to city businesses that could become customers or partners. And if she really believes in a startup’s new product, a mayor could offer a chance to test it through an unpaid city pilot. Some startups may ask for a token payment to show they can close a deal, and that’s OK, too.

The nonprofit Institute for Local Self-Reliance, which has been advocating for locally based economic development for over 40 years, earlier this year produced a report that outlined eight city-based policy strategies that can form part of a comprehensive homegrown economic development strategy. In addition to setting up a small business office (like the startup office Zipper cites in Seattle), these policies include designing retail to favor local businesses (such as using zoning to ensure smaller spaces are available for local businesses to rent, potential set-asides for local businesses in larger retail developments, and limitations on the density of so-called formula or chain stores); rules that facilitate the adaptive reuse of old buildings, as Phoenix has done; expanding access to capital through loan funds; giving slight bid preferences to local business, as Cleveland, Ohio, has done; and shifting economic incentive dollars to support local business, as NPQ covered earlier this fall in Asheville, North Carolina.

“To summarize,” Zipper writes, “if you’re a city official ready to adopt a grow-your-own economic development strategy, make it easier for prospective entrepreneurs to take the plunge and celebrate them when they do. Simplify business regulations, tweet about successful startups, offer to do a city agency pilot, and introduce entrepreneurs to resources in the community.”

“And while you’re at it,” Zipper adds, “pat yourself on the back for doing something more productive than climbing aboard the HQ2 bandwagon.”—Steve Dubb