Late last month, Harvard hosted its annual social enterprise conference, held virtually this year due to COVID-19. Organized by graduate students at the university’s business and public policy schools, the official theme was of “resilience and reckoning.” A more accurate description might be “the search for a better capitalism.”

NPQ has covered this conference before. Two years ago, philanthropic critic (and former McKinsey consultant) Anand Giridharadas headlined, telling conference goers that “plutocrats are going to plute” and advising graduate students in attendance to not fall for the false story, as he initially did, that “you can change the world by adding ‘impact’ to the front of whatever word that you are doing.” Yet, as Katerina Manoff noted in NPQ, that talk by Giridharadas was followed by a panel that “cheerfully discussed the technical aspects of asking investors for money.”

This year’s conference, held after a year of COVID-19 and an historic uprising against anti-Black racism, had greater coherence than that gathering of two years ago. Keynote speakers included former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, who after leaving the governor’s office went to work as an impact investing advisor for Bain Capital, and London-based economist Mariana Mazzucato, whose website literally claims she’s “on a mission to save capitalism from itself.”

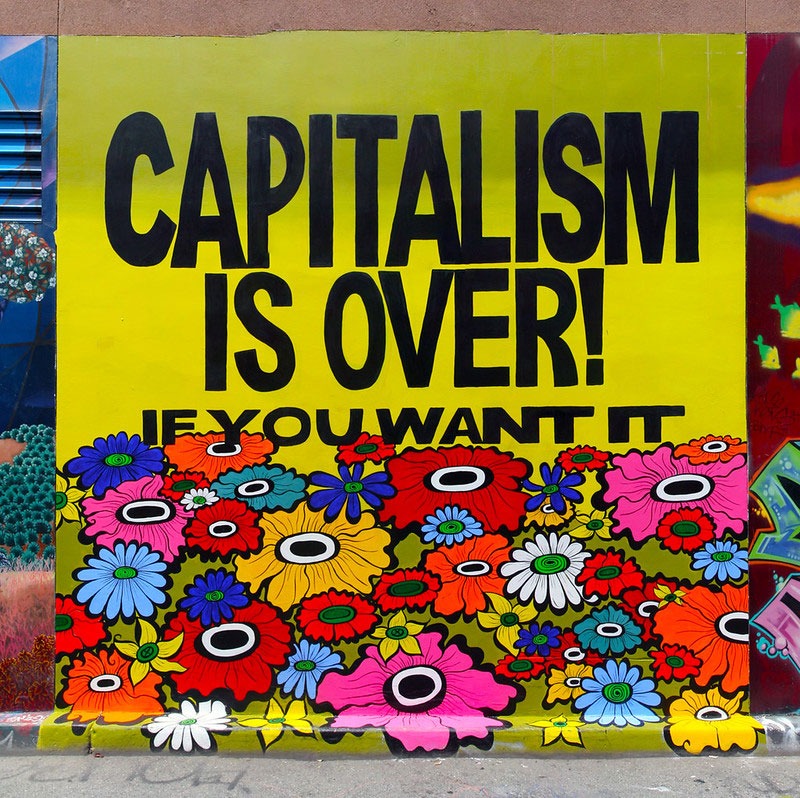

There is, however, still something odd about this search for a better capitalism. Why a better capitalism and not a better economy? You don’t have to adhere to the theories of Karl Marx to recognize that in capitalism the small minority who possess a key limited resource—i.e., capital—leverage that resource to extract greater value for themselves at the expense of the overwhelming majority who lack access to it. And one would have to be pretty oblivious not to notice that who has capital and who doesn’t is not merely (or even primarily) the result of “merit,” and instead is often the product of wealth accumulated via land theft, genocide, enslavement, imperialism, and ongoing racism and patriarchy—to name a few contributing factors.

Arguably, and surely this is the implicit unstated idea of the speakers at the Harvard conference, the best society can do is to ameliorate capitalism’s costs. This concept lies at the heart of what in Canada and Europe is typically called social democracy. And while the term “social democracy” is less common in the United States, the same idea does show up in the US, too—in some versions of a Green New Deal, for example. But even the notion that something better than capitalism might be possible remains largely unthinkable and therefore is only rarely thought.

This unwillingness to consider alternatives leads to some odd discourse. In his keynote remarks, for example, Patrick both said, “It should surprise no one that capitalism is in decline” and “Yet I am still a capitalist.” Patrick added that, “You can’t any longer separate financial value from social and environmental value.” Yet in a world where the net worth of Jeff Bezos has climbed to nearly $198 billion from $113 billion one year ago, even as Amazon employees must pee in bottles to do their jobs, it would seem that, just maybe, you can still separate financial value from social value.

To be fair, Patrick calls for reforms, lifting up employee ownership as one way to reduce inequality. Patrick also supports higher taxes and greater regulation of firms to shift the focus of business from quarterly earnings to long-term creation of value. Still, at the conference, Patrick was hardly the only one to illustrate a deep desire to describe the world as it should be, rather than the world as it is. That said, the conference did open a window on debates at both business and policy schools today regarding the economy—and it is to these debates we now turn.

Paths to Reform, Two Views

The Harvard conference contained a number of panels that looked at impact investing and community finance, with a focus of how to drive more capital into BIPOC communities. On one panel, Donna Gambrell, head of Appalachian Community Capital and a former head of the federal Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund, lifted up the importance of CDFIs as “financial first responders.” The nation’s 1,200 CDFIs, Gambrell explains, provide lending and business advisory services and, as NPQ covered last year, “stepped into the breach” when federal programs like the Paycheck Protection Program excluded many BIPOC-owned businesses. Last December, the CARES 2 bill provided $12 billion for CDFIs to support recovery, many times their typical $250 million annual allocation. “Here,” Gambrell observes, “is an opportunity to make sure that funding goes to CDFIs that look like the communities that they serve.”

At a lunch panel that also focused on shifting capital, Morgan Simon, a founding partner of the Candide Group, noted some of the vast disparities that exist. “In traditional venture investing,” Simon points out, “less than 10 percent of the capital goes to people of color and women.” Her firm, Candide, by contrast, invests 75 percent of its capital in women- and BIPOC-owned firms. Simon has also been a strong advocate of eliminating private prisons, attracting a harassment lawsuit (ultimately dismissed by a judge last November) filed by private prison firm CoreCivic.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

At the same time, Simon recognizes that shifting financial capital is only one of what she outlined as “four parts” to system change. In addition to finance, there is, Simon indicates, also a political element, a cultural element, and a spiritual element. “We have to be conscious of when we use which tool,” she adds. Philanthropy, for example, Morgan contends, can be most effective by funding movement groups so that they can advance policy change through advocacy and organizing.

In terms of broader shifts, Simon notes that the present cultural primacy of finance leads to odd results. Right now, she observes, investments that prioritize mission over financial return, such as program-related investments, are treated as carve-out exemptions to financial norms. But maybe mission-based foundations should need to ask for exemptions if they wish to violate mission norms. As Simon puts it, “If I’m an environmental foundation, shouldn’t I need an exemption to invest in fossil fuels?”

Government and Business: A Changing Relationship

Two speakers—Chris Jurgens, director of the Reimaging Capitalism program at Omidyar Network and who was part of a panel on the future of capitalism, and keynote speaker Mazzucato—both focused their remarks on changing the relationship between government and business. Jurgens, for his part, contends that, “The role of government and regulation needs to be reframed. Not just fixing market failures and curbing excesses, but the fundamental role of government in shaping markets.” Jurgens lifts up the well-being index being promoted by New Zealand as an alternative to gross domestic product as an example of what he envisions. More broadly, Jurgens calls for what has often been labeled as corporatism. “In Europe, business and government and labor are adversarial but they are at the table,” Jurgens observes. “We’ve lost that set of muscles in the United Kingdom and the United States.”

Mazzucato, in conversation with Harvard economist Dani Rodrik, advocates more far-reaching changes in the state’s role. In Mazzucato’s view, “The COVID moment is a time to rethink outside of the box.” Within economics, Mazzucato observes, the public sector is typically viewed as “putting patches in the system.” These include such items as public goods (e.g., libraries), addressing externalities (e.g., pollution regulation), information failure (e.g., standard setting), and regulation of imperfect competition (e.g., antitrust). In short, government or the state in this view acts to address “market failures” but otherwise stays out. Mazzucato, by contrast, contends that the state must become the “co-creator” of markets.

Mazzucato identifies four other myths that she wishes to challenge. Among these are that only business creates value, that government should be run by business efficiency standards, that government saves money by outsourcing analytical work to consultants, and that governments should not “pick winners and losers.” The economy, notes Mazzucato, “has not just a rate of growth, but a direction,” and it is the government’s role to choose that direction, which will, necessarily, favor some firms and harm others. For example, a Green New Deal will benefit solar and wind energy producers and harm fossil fuel companies.

Mazzucato calls for organizing government initiative around “missions,” using the Apollo space program as an example. But to extend the Apollo metaphor a little further, rockets can blow up, so a society that took that approach to governing would need to have a higher tolerance for failure than is common today. “Governments should be able to mess up along the way,” she notes.

During President Barack Obama’s administration, the US Department of Energy lent $30 billion to 30 “green” startups. Everyone remembers the failure of Solyndra. Fewer recall that another of those 30 firms was a small startup named Tesla. Foolishly, Mazzucato observes, the Obama administration not only failed to communicate what it was doing but failed to “socialize the rewards.” Tesla stock could have more than paid for Solyndra’s failure. As Mazzucato explains, when government invests in businesses, taking “equity stakes or shares makes a lot of sense.”

Better Capitalism or Better Economy?

In reflecting on the conference, clear themes rise to the top: the need to shift capital to BIPOC communities, a call for new business regulatory frameworks, and the need to reconceptualize the role of the state. There were also some deeper themes that were conspicuous in their absence, such as reparations or the possibility that we might need to move beyond capitalism, not simply improve it.

At NPQ, we have addressed economic system change before and have even highlighted specific proposals. Expanding the bounds of discussion in this way does carry some risk of losing connection with immediate on-the-ground needs, but it can also open space to new thinking that can generate more effective answers to myriad social challenges.

It is helpful, fundamentally, to ask the right question. Preserving capitalism—no matter how much “better” than today—is not the goal. Building an economy that generates wealth, distributes that economic bounty fairly, and sustains the planet is. Perhaps an improved capitalism can deliver on those economic goals, but maybe not. One thing, at least, seems clear: the sooner we ask the right questions, the more likely we are to develop the solutions we need.