As a part of the job description, all nonprofit executives manage the tension between the pursuit of mission and the preservation of organizational and financial viability. This tension exerts pressure on day-to-day operations, and while it sometimes seems that one role dominates the other, in a healthy organization they always must be balanced.

Actually, three key factors interact to sustain health over time. The first two points of this triad are mission and organizational capacity, which are familiar to all. The third is equally important but less well understood: capital structure. I will refer back to this triad later in the article.

Capital structure is sometimes invisible but never absent. There are four principles to remember:

- First, and fundamentally, capital structure exists in even the smallest nonprofits; ignoring it puts an organization at risk.

- Second, capital structure always has an impact on mission and program, and on organizational capacity.

- Third, capital structure is linked directly to a nonprofit’s underlying business, which is distinct from, though clearly related to, its program.

- Fourth, healthy capital structures are difficult to maintain in nonprofits because there often are restrictions on nonprofit assets; this creates a “super-illiquidity,” or lack of financial flexibility, that makes it difficult to keep the “business” aspects of nonprofits functioning well.

What Is Capital Structure?

Capital structure, as described in “Elements of Capital Structure” is the distribution, nature and magnitude of an organization’s assets, liabilities and net assets. Every nonprofit—no matter how small or young— has a capital structure. There are many kinds of capital structure, and there is no such thing as one “correct” kind. It can be simple, with small amounts of cash supplemented by “sweat equity” and enthusiasm, or highly complex, with multiple reserves, investments and assets.

Let’s look at an example: a school. Typical schools have classrooms with desks and chairs, teachers and administrative staff who are paid on a regular basis, computers and other equipment, and varying amounts and kinds of receivables (a school’s receivables might include multi-year pledges in a capital campaign, tuition owed, government funds to reimburse per-pupil expenditures, and certain kinds of grants). Sometimes the school has been financed by a long-term loan (a mortgage or tax-exempt bonds). Sometimes it draws on a line of credit at a bank or a cash reserve to fund payroll before tuition has been received. Some schools have endowments that are invested and produce income to help subsidize operations. Some own vehicles, art or substantial tracts of land.

The combination of these elements translates into the school’s capital structure. And decisions affecting it–how large a building, whether to finance it or not, how many computers, etc.—not only affect organizational capacity and program, but also affect the financial viability of the operation.

Capital Structure Pushes Us Organizationally

Growth and change affect capital structure—more students means more desks, chairs, computers, and teachers, and therefore more space, cash and receivables. Expansion of program requires expansion of capacity, which requires expansion of the balance sheet as a whole, not just one part.

Conversely, changes to capital structure often drive changes in organizations and programs. With large investments, small or young organizations can become larger overnight. This will bring increased levels of organizational complexity, often with greater proportions of fixed assets, as well as implied longevity of the current institutional and programmatic identity. This has a profound effect on the long-term effectiveness and flexibility of the program itself, and it tends to fuel more growth and change (and the need for capacity building).

Let’s build on the example above with an account of how a change in capital structure—in this case the drama of a new building—can affect program and organizational capacity.

Organizations whose leadership anticipates the need for an overall growth of assets to accompany the massive growth in “property, plant and equipment” typically have the greatest success in managing the construction of new buildings. Without such attention, these projects pose major hazards even when the bricks and mortar are all in place. The investment looks great on paper, expanding the organization’s unrestricted net assets. But program success requires that cash be maintained in balance with the new building, or the program will be hurt.

This is intuitively obvious with respect to the need for cash and, generally, unrestricted revenue. It may be less obvious that cash reserves need to be expanded or rebuilt as part of the new capital structure. These expansions, which need to be relatively permanent, might take the form of expanded reserves or credit lines, which will be needed to finance the expanded business cycle (more students means higher receivables, a bigger payroll, more insurance to prepay, and therefore potential cash flow concerns). Or they may take the form of permanent working capital to finance programmatic and administrative needs generated by the growth: more marketing, program development, administration and development staff for the larger enterprise.

Intermittent cash flow problems, inadequate reserves and raided endowments often result from a lack of such planning. In turn, these cash flow problems lead to imbalances that starve discretionary areas of activity such as program innovations, staff benefits or maintenance of buildings.

In fact, no matter how good a fortuitous chunk of capital may look, some projects are simply too big with respect to where the organization is in its development. A dance company’s development director put it this way:

“We needed to expand to accommodate the new works the artistic director was planning. So we decided to create our own performing space. The board was enthused and raised $2 million…but…now we need more operating money to fund production costs and operations. It looks as if the artistic director needs to do nothing but raise money full-time for the next eight months. That knocks out the first part of the season that he’s supposed to choreograph. We realized this last week and we’ve already announced the season with his works.”

The image here is the well-known drawing from The Little Prince where a boa constrictor has swallowed an elephant and ends up looking like a man’s hat.

An inappropriate capital structure often elevates fixed costs, freezes resources and pushes program growth beyond what is healthy to maintain quality. In the example above, the point is not that buildings are bad, but that planners of these projects must understand the bigger picture—and the need for growth of the whole balance sheet and operations, including, most importantly, the program—to fully realize the great potential of a good capital project.

While not all effects of an unplanned change in the balance sheet are as dramatic as these, the result of inadequate and unbalanced capitalization is a systematic under-investment in your enterprise as a whole, which over time will undermine organizational capacity and achievement of the mission.

Core Business Differs from Program

The notion that “programs” differ from “businesses” is not widely understood in the sector. Nonprofits, reasonably enough, are typically grouped, evaluated and funded based on their programs—such as social services, arts, education, health, etc.—because program and mission are primary.

Funders, however, don’t give mission or program; they give money, which is converted into program accomplishments via operations. Their grants necessarily have business implications (sometimes unanticipated) that shape capital structure and ultimately, programs.

Organizations that have common overall goals in one field of practice may choose diverse program tactics and therefore diverse business strategies. For example, several organizations may share the mission of “protecting the health of low-income children.” One program goes door to door to deliver immunizations; another establishes a walk-in family health clinic; a third creates preventive public health curricula and advertising to educate parents and children; and yet another advocates for expanded health care funding by government. While they claim the same ultimate goal—and might even be funded by the same foundations or government agencies—their underlying “core” businesses are quite diverse. Each implies a different capital structure.

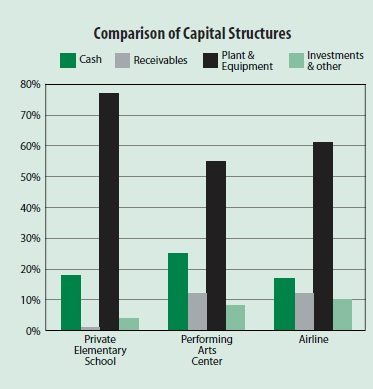

Conversely, organizations can have varying missions but very similar core businesses: an arts organization, a school and an airline, for example. Even though they have widely divergent missions, they have in common the business of filling seats. That fact drives their core business and is required to create the revenue that is earned by fulfilling their missions. Ticket sales or tuition essentially buy the right to sit in a seat.

While it is highly relevant to mission that the theater is presenting the finest repertory theater in the world or that the airline eventually will fly its seats to Paris (with you in them sipping champagne and nibbling pate), or that the school has the best chess team in town, these are all, from the core-business point of view, simply means to get people to sit in the seats and pay money.

What is relevant to capital structure, at the business operation level, is that these three organizations always need to figure out how to buy or rent those seats, to pay for them, keep them relatively comfortable, expand them, contract them, charge more for them, and sell more of them. In addition, they have to adequately pay and support great artists, pilots, teachers and other related program people to fulfill their missions.

Notice how similar the asset side of their balance sheets looks in the “Comparison of Capital Structure” graph. Their characteristic patterns of assets exist whether the pilot or artistic director is good or bad, whether the board consists of geniuses or ninnies, whether the executive director has gone to nonprofit management training or not, and whether people show up to sit in the seats. And if this graph changes, they have probably changed their core business.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Restricted Assets

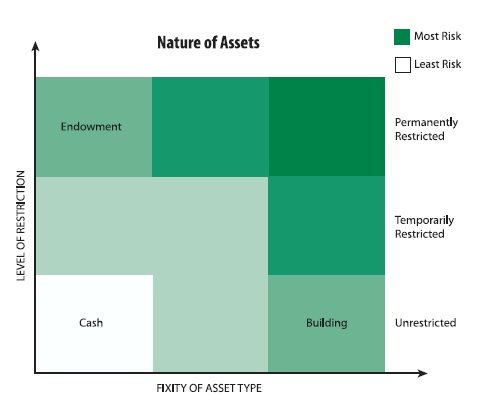

In both the nonprofit and the for-profit worlds, assets consist of familiar balance sheet items: plant and equipment, receivables, cash, etc. In both worlds, assets have varying degrees of liquidity or illiquidity inherent to the nature of the asset. In the business world cash is highly liquid; receivables are less so, with their liquidity dependent on how quickly they are collected and become cash. Buildings, which require sale to realize cash, are even less liquid.

In the nonprofit world, however, both assets and income can be restricted by donors. This creates a situation where their essential nature is altered or emphasized. Cash can become non-fungible, or hard to move around and use–essentially illiquid. Substantial cash net assets, such as permanently restricted endowments, are in this category. This state of illiquidity also applies to increased receivables, yielding cash that can be used only for a certain purpose, and to a building, particularly one whose use or sale is restricted. This “super-illiquidity” is depicted on the “Nature of Assets” chart.

In “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Coleridge wrote, “Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink.” This states the problem of illiquidity well. We can restate it thus: “Assets, assets everywhere, and we can’t make our payroll this week.”

Donor restrictions on either assets or income, coupled with the nature of the asset, create risk and expense because they are more likely to create demands on capacity and program beyond what the donor originally envisioned and what may have been planned for by the nonprofit.

For instance, most nonprofits have some experience with restricted grants and contracts creating expenses that they do not fully cover. Often such restricted grants may be for new or expanded programs, and they rarely provide for the totality of additional staffing and operational costs that accompany program growth. Equally rarely do they provide for the attendant expansion to the balance sheet in the form of cash reserve, additional plant and equipment, and the like. (See Elizabeth K. Keating, Nonprofit Quarterly, Spring 2003)

Growth through temporarily and permanently restricted revenue and assets, as well as through the expansion of assets that are illiquid simply by their nature (buildings or computers, for instance), creates greater organizational risk because it drives increased demand for the unrestricted income that is needed to add to program and organizational capacity.

The Paradox of the Poor Little Rich Organization

The notion that money and investment create expenses when donated is counterintuitive for most people, and the idea that an endowment challenge grant could be destabilizing is especially so. Let’s look at how a $1 million contribution to an endowment for a theater company does both.

Let’s say a certain Mrs. Glitterbosom makes a $1 million cash contribution to create a permanently restricted endowment for the HelioTroupe Theater Company with the stipulation that the recipient must raise a similar amount to match it. She restricts the gift to new program development in a particular area—say, for the production of “living theater”1 (in which she is somewhat of an expert). The HelioTroupe Theater has excellent programs, is lean but well managed and pretty well capitalized. It has annual revenue of $1 million—60 percent of which is earned, mainly between October and March—and a cash reserve of $200,000, which is used to fund pre-production costs for shows. It employs 12 people, eight of whom work roughly full-time on program and production and the other four of whom raise money and run the support operation. This addition has the added value of extending their mission of presenting artistically path-breaking, socially relevant material.

Who would turn away $1 million to support something their organization is committed to? No one in their right mind! But there are real potential threats to HelioTroupe’s capital structure in this situation. An endowment, like a capital building project, imbalances the capital structure and puts pressure on the other two points of the nonprofit management triad—mission and capacity.

How does this happen?

Matching the $1 million endowment creates an immediate demand for fundraising efforts—and of course the match will also be restricted. This requires a draw on unrestricted cash (to pay for increased fundraising capacity) while diminishing its future availability, since fundraising will focus on restricted cash for endowment. The program restrictions will create other pressures. Artistic staff will be expected to develop new works and present them, which will require draws on the existing cash reserve (now used to front about $600,000 in revenues from shows). If the calendar of shows is expanded, the cash reserve will need to be permanently expanded as well to cover cash flow, receivables and the like. This requires more fundraising and management capacity. Moreover, the new shows are more likely to be risky with respect to revenue, so the wise course would be to ensure that the cash reserve can be replenished if necessary.

But won’t the Glitterbosom Endowment for Living Theater produce revenue in the form of interest income to defray some of these costs? The immediate projected income of about $50,000 (an estimated 5 percent realized return, which is optimistic in these times and probably too much to ensure growth of the endowment itself) will allow the organization to expand by about one-half a fully supported person. This amount is arguably inadequate for the development of new programs and to also pay for the increased program and administrative toil that will accompany the creation and rollout of new works, and it definitely is inadequate to fund the ongoing cost of increasing and maintaining reserves, beefing up fundraising and adding supporting administration. Even the eventual $100,000 in “new money” from interest on the matched endowment will be restricted to new works, requiring more unrestricted cash rather than filling the need for it.

The point is not that endowments are a bad idea, nor that the challenge grant described here is an opportunity to be avoided. The point is that this endowment created a significant change in capital structure that neither management nor the donor took into account. And any change to one point in the triad–even the addition of thrillingly large amounts of capital in the form of endowment—requires adjustments in the remaining two.

The Quandary of Nonprofit Growth

In the business sector, profits are used to fund working capital and other growth needs. During growth or startup, businesses budget for unprofitable years, sometimes several of them, and have tools to plan for and fund these deficits. With these planned deficits, the business is investing to build the market and infrastructure it needs to succeed. Among nonprofits, profit margins are frequently thin, discouraged or simply prohibited. Both government contracting rules and nonprofit culture discourage the development of operating surpluses (If you have a surplus, why should we give you a grant?) or induce nonprofits to hide them.

The truth is, not only is it difficult to afford the management improvements that must accompany growth, it is difficult even to afford the ongoing improvements necessary to maintain effective and efficient operations without growth. As a result, management (as opposed to program) is frequently staffed too thinly and under-supported in relationship to program. Financial systems often are rudimentary, and while small and medium-sized agencies have staff with sophisticated, specialized program expertise, they frequently lack the increasingly specialized fundraising, planning and financial management skills that become crucial during growth. The irony is that a technique meant to control costs and focus efforts on mission actually undermines efficiency and harms program.

There are many such trap doors associated with the largely unrecognized issue of capital structure. For instance, programs meant to build capacity in nonprofits very often don’t address the need for attention to capitalization, ultimately limiting what they can accomplish in terms of promoting sustainable organizational health. Organizational depth and sophistication require capital planning and organizational slack. This means we should encourage in the organizations we care about occasional periods of time when capacity exceeds what is required simply to operate current programs. Without such foresight, even the most promising nonprofits are sentenced to the purgatory of marginal improvements, usually after a lag time during which inadequacies are glaringly apparent.

Putting Capitalization on the Agenda

The reasons for the neglect of capitalization run deep in nonprofit culture. Managers, employees and funders share the belief that energy, willpower, stamina, and enthusiasm can overcome all obstacles, and that where it does not, some sort of personal failing is to blame. The idea that an inappropriate capital structure can subvert an organization’s ability to meet its objectives can seem overly deterministic, even fatalistic. In the face of adversity, the temptation is to say, “We must work harder,” rather than to look at the balance sheet–where money is or is not allocated—for systemic reasons for failure.

But what works for small organizations rarely works for larger, more complicated institutions, and vice versa. In other words, “sweat equity,” and an organizational culture (and capacity) driven mainly by stamina or enthusiasm, does not scale well. A major mental health organization doesn’t use amateurs to treat severe mental illness. Conversely, a small group of enthusiastic graduates who want to experiment with new approaches to teaching through theater may do best with the least “infrastructure.” Neither is better, but each model implies differing capital structures and capacity requirements, and each has a different array of programmatic choices. Capital structure, then, changes as organizations go through various stages of development and growth.

Capitalization as a concept is not typically a part of the current nonprofit lexicon—nor that of funders. Although, as was stated at the beginning of this article, all nonprofits have a capital structure, the lack of a rational approach to it is a largely unnamed and therefore quietly powerful problem. Because capital structure is not an explicit part of practice, people don’t even know it’s missing.

Reversing the nonprofit sector’s neglect of capital structure requires both a broad-brush advocacy and education campaign and the changed habits of individual nonprofits and funders. The leadership of organizations must begin identifying their core businesses—how they get and spend money to accomplish their missions. From there they can make capital structure an explicit part of strategic planning. Boards, consultants and nonprofit managers can then turn their attention to questions such as: What does our capital structure look like, and what should it look like? What priorities does it imply or demand? Is it appropriate for our purpose and plans? How will growth affect it? Will it improve or go out of balance as a result?

Funders can be a powerful force in improving things, because their grants have such a major impact on capitalization. By confining their funding to the marginal costs of programs that are relevant to the pursuit of their own missions, funders may unintentionally contribute to the systemic under-capitalization of the sector–controlling rather than developing it, and encouraging the growth of programs without providing for the commensurate growth in capacity. The attached guide, “Capital-Savvy Principles for Grantmakers,” may be instructive in reversing this trend.

Endnote

- For the uninitiated, living theater, as a genre, mixes art and politics in productions that are highly engaging and confrontational with audience members.

Clara Miller is president of Nonprofit Finance Fund, a community development financial institution that is a leading source of financing and advice for nonprofits nationwide. As principal author of this work, she drew on work undertaken by AEA Consulting, with additional contributions from Norah McVeigh of NFF.