In addition to grants, foundations have been increasingly using Program Related Investments, or PRIs, to support nonprofits. PRIs can be a powerful tool to support foundation and nonprofit missions, but they only fit some projects. Understanding their value and uses can be useful for both foundations and nonprofits. For foundations, knowing the ins-and-out is vital to use the tool effectively. For nonprofits, understanding how PRIs work can help your organization assess whether this tool is right for you. For both, it is important to understand when PRIs are good funding sources, what they can be used for, and what good PRI terms look like.

What Is a PRI?

A PRI is a loan, equity investment, or guaranty made by a foundation in pursuit of its mission, rather than to generate income. The recipient can be nonprofit or for-profit, although most PRI recipients are nonprofits. The US Internal Revenue Code treats PRIs similarly to grants. In contrast to ordinary, market-based investments from their endowments, foundations do not expect PRIs to produce market-rate returns.

The concept of PRIs originated in the US Tax Reform Act of 1969. Since then, foundations including Ford, Rockefeller, MacArthur, Packard, and Annie E. Casey have used PRIs creatively to further their charitable missions. More and more foundations across the nation are choosing to use this tool.

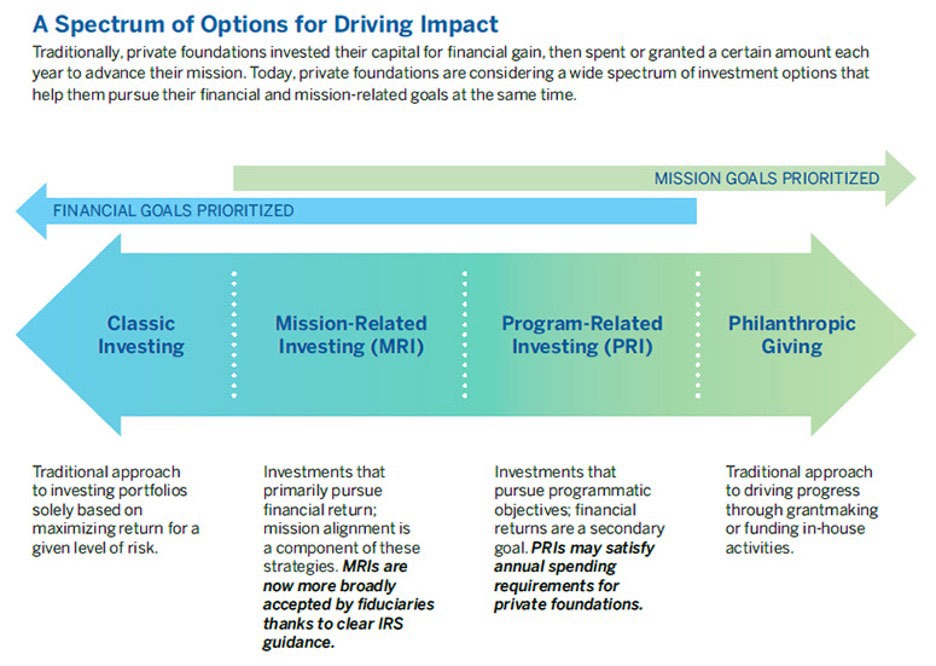

PRIs are conceptually and legally distinct from two other kinds of socially minded investments made by foundations: Mission-Related Investments (MRIs) and Socially Responsible Investments (SRIs). MRIs and SRIs are investments made out of the corpus of the foundation. PRIs, by contrast, come out of a foundation’s grantmaking budget.

The US Internal Revenue Code defines PRIs as investments that meet three criteria:

- The primary purpose is to accomplish one or more of the foundation’s exempt purposes;

- Influencing legislation or taking part in political campaigns on behalf of candidates is not a purpose; and

- Production of income or appreciation of property is not a significant purpose.

PRIs count toward a foundation’s qualifying distributions—the required annual payout of five percent of its endowment.

Who Makes PRIs?

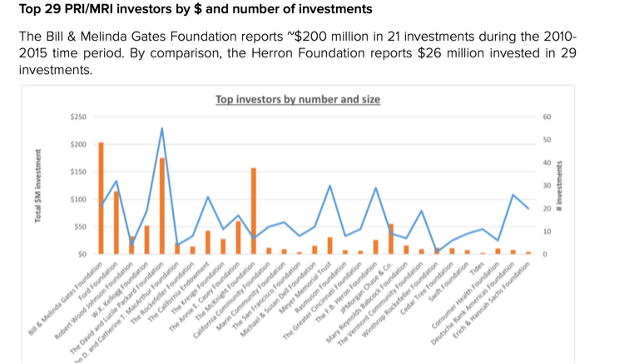

The philanthropic sector is increasingly understanding how PRIs can be used. Some larger foundations have entire departments with large investment portfolios that are dedicated to PRIs. Smaller foundations may have invested in one or two PRIs, either by themselves or in partnership with a larger foundation. The chart below shows some of the top U.S. foundations that use PRIs as a form of investment.

Case Studies

PRIs can seem intimidating to both the recipient and the investor if neither have participated before in a PRI arrangement. It is important that the project be a good fit for this source of capital. Below are two examples of projects that have used PRIs to leverage their impact.

Providing Low-Interest Loan Capital: Rural Women-Led Business Fund

First Southwest Community Fund (FSWCF) is a nonprofit based in Southwest Colorado that provides equitable access to capital for small businesses, startups, and nonprofits. PRIs are an excellent capital source for nonprofit loan funds, as there is a clear source of repayment. First Southwest Community Fund used a combination of PRIs and grant capital to fund their Rural Women-Led Business Fund. This fund is designed to create access to funding for women-led/identifying entrepreneurs and small businesses in rural Colorado, with a focus on serving women of color, through loans, education, and technical assistance. One foundation participating in the Rural Woman-Led Business Fund is providing a $500,000 PRI at a one percent interest rate for a 10-year term (for the loan fund) and a $250,000 grant for programming. Another foundation is providing a $300,000 PRI at no interest for a five-year term and a $100,000 grant for programming. By combining these capital sources, FSWCF is able to provide a low-interest loan fund of $800,000 that offers loans up to $75,000 to women-led businesses in rural Colorado. Loans are provided to businesses at an interest rate between one and three percent—far lower than most bank loans. The PRI structure means that FSWCF can both repay the PRI and cover administrative costs while developing a loan loss reserve. In addition to these PRI loans, grant dollars are used for educational programming and to invest in pipeline development through accelerator programs, mentorship, and high school programming.

Denver Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Fund

The Urban Land Conservancy, Enterprise Community Partners, the Denver Office of Strategic Partnerships, and several other investors partnered to establish the first affordable housing TOD acquisition fund in the country.

The purpose of the Denver TOD Fund is to support the creation and preservation of over 1,000 affordable housing units through strategic property acquisition in current and future transit corridors where the city’s light rail system is being built. The Fund answers a basic real estate conundrum: when the economy is bad, property values are low and ripe for purchase, but access to capital is poor and affordable housing developers are scarce. These economic down times provide the opportune moment to invest in real estate around proposed transit stations in order to capitalize on lower property values and preserve affordable housing before the city’s light rail system is fully operational.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The partnership of government, quasi-governmental organizations, banks, nonprofits, and foundations, combined with the use of PRIs, grants, equity investment, and traditional loans are critical components of the Denver TOD Fund.

Enterprise Community Partners assembled the initial $15 million in capital that allowed the Fund to begin operations in 2010. The City and County of Denver is the largest single investor, providing $2.5 million in first loss investment. ULC committed the initial $1.5 million equity to the Fund and leads the real estate acquisition, management, and disposition of assets for the Fund. The Rose Community Foundation made the first PRI to the TOD Fund for a Colorado-based foundation. Several other foundations later put in PRIs as the Fund expanded. Since then, the Denver TOD Fund has been seen as a model throughout the country.

The Denver TOD Fund was capitalized at $15 million but has now grown to $24 million in total loan capital. This revolving loan fund makes capital available to purchase and hold sites for up to five years along current and future rail and high-frequency bus corridors in metro Denver. The $24-million fund leverages over $500 million in local economic activity, supporting construction and permanent job generation in many low-income neighborhoods. The Fund also directly benefits low-income households that on average spend 60 percent of their gross income on housing and transportation. By controlling these expenses and providing access to quality, environmentally sustainable housing, the TOD Fund makes it possible for families to build wealth and access employment and educational opportunities. It also provides employers with access to an expanded workforce.

Nonprofit Considerations for Taking on PRI Debt

PRIs can be of great benefit for many nonprofits, but they are still fairly new to many, and it’s crucial to understand how they work. Some questions a nonprofit should consider when approaching a foundation for a PRI are:

Is your project/organization a good fit for a PRI? Two key matters to consider here are your ability to repay the PRI and how you intend the use the money. Regarding the latter, a PRI most often makes sense when a project requires a high level of up-front capital, such as affordable housing, business start-up, farming, and other large capital projects. Revolving loan funds are also often a good fit for the PRI model.

Do the terms meet your need? Foundations often dictate the term length based on their PRI policy, but it’s important to take into consideration how you plan to use the PRI. If the PRI term is not long enough for you to be able to repay it, it is not a good idea to take on this form of capital.

Who gives PRIs in your local area? Let’s say that your nonprofit is interested in getting a PRI low-interest loan. How do you find a foundation willing to provide one? One key step is to ask your current foundation supporters if they provide PRIs. If not, you can research whether other local foundations provide PRIs or if your project might fit national foundation priorities. You can also sometimes leverage foundations that already provide PRIs to help other foundations consider using this tool.

Assuming you find a wiling PRI provider, other factors to consider include the following:

- Interest rate: Normally, PRI interest rates fall between zero and three percent. Sometimes, the rate varies depending on the level of impact achieved.

- Repayment schedule: These can vary. Some PRIs require monthly payments. Others allow the nonprofit to make payments on a quarterly or annual basis.

- Covenants: Different foundations may require different covenants as part of the PRI terms. Some foundations may require that your project has income that generates a specified debt service coverage ratio, for instance.

- Reporting requirements: Like grants, PRIs require foundation reports, so it is important that the nonprofit knows what these reporting rules are.

- Due diligence: Foundations vary on how much information they require to make a PRI. Some foundations may contract with a consultant to perform a deep dive into the project or organization. At a minimum, you will likely be expected to provide two-to-three years of financial statements.

- Legal documents: This can be challenging for smaller nonprofits, or nonprofits that are not familiar with loan documents. It is advisable to consult with a lawyer or consultant to help you review the PRI documents. Sometimes foundations may help with this. Generally, you can expect that the following legal documents will be required: a) letter of intent, b) PRI loan agreement, c) promissory note.

Making the PRI Case to a Foundation

PRI investments are driven by impact. However, unlike a grant, they have a risk rating, as the goal is for foundations to at least get their investment back, hopefully with some interest. Key things to consider when making a case to a foundation for a PRI include:

- Impact: Here, it’s important to show how the PRI will help your nonprofit achieve its goals and why achieving those goals matters.

- Risk: Yes, PRIs are supposed to be risk capital. But foundations—surprise!—are often conservative, so showing a track record of success and strong community partnerships can allay risk concerns.

- Capacity: A foundation will want to know who is on your team and how you will track both social impact and loan repayment.

- Partnership: Taking on a PRI is a partnership—perhaps more so than a grant which can sometimes be a one-time transaction. If the foundation is aligned with your values and mission, it is more likely the PRI-funded project will be successful.

To PRI or Not to PRI?

PRIs are not for everyone. But when you have a project that requires large, up-front capital input, PRIs can be a useful option. They may also allow you to seek funding from a source that might otherwise not be accessible. These days, many foundations are looking to grow their pipeline of PRI investments. Understanding PRIs may help you achieve your organization’s goals.