The world changes too much for anyone who is invested in social change work to imagine that this work is linear and predictable. Opportunities come and go, whether caused by a pandemic or political shifts. This much most social movement leaders and activists intuitively understand.

But what can be done with this realization? How might movement groups better prepare for moments of opportunity? We want to explore how we can create the changes we want to see by responding to the changes that are outside our control.

A Missed Opportunity

It may seem an obvious point, in theory, that social movement leaders and activists need to plan for the unexpected. But this is harder in practice. One of us (Dave) learned this lesson early in his career, at a moment when he and his colleagues had failed to plan for an opportunity.

Back in the mid-2000s, before the likes of George Santos or Donald Trump normalized daily political scandals, there was another name that had become synonymous with Washington corruption: Jack Abramoff. He was at the center of a scandal involving bribery, kickbacks, money laundering, and expensive gifts for members of Congress, including golfing trips to Scotland.

Abramoff ended up pleading guilty to a range of charges. So did Representative Bob Ney (R) of Ohio and a handful of congressional aides. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R) of Texas also resigned and was convicted of money laundering.

It may seem an obvious point, in theory, that social movement leaders and activists need to plan for the unexpected. But this is harder in practice.

At the time, Dave worked for an organization focused on government accountability and reform. They often struggled to get public attention on Congressional corruption. The Abramoff scandal suddenly changed that: the investigations brought details of dirty influence peddling to the front page. If your mission was to curb corruption, it was a prime moment to do something bold.

Dave’s organization held a meeting. They started talking about how to build pressure on Congress. Could they engage activists to call their representatives? Get partner organizations that usually focus on issues like environmental protection or healthcare to take up a process issue like lobbying reform? Convince local media outlets to look at state-level aspects of the story? These were important questions, but halfway through the meeting, Dave realized they hadn’t answered the most important question: what was their goal? They could mobilize public pressure, but to do what?

He learned quickly that they didn’t have a campaign goal yet. Even worse: they didn’t have a policy platform on the issue. If a journalist had called their office for a comment, they could clearly state why Abramoff’s actions were bad and how they represented systemic corruption in Washington. But they didn’t have clarity on how Congress or anyone else could fix that system.

They were trying to plot a route without a destination in mind. In a fast-moving political moment, they could have advanced groundbreaking legislation. Instead, they first had to collect themselves and decide what they wanted to achieve. If they’d had a goal ready, they might have also had draft legislation ready. But they had none of that.

In responding to scandals—as in comedy, in cooking, and in stock trading—sometimes the most important ingredient is timing.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Opportunity Windows and Overton Windows

The Abramoff scandal highlights something that may seem obvious, but that often isn’t made explicit: opportunities for change shift over time. There are moments when new things become possible. If you’re not ready, then you’re going to miss it. If there’s no opening right now, sometimes the best approach is to prepare for the next one.

Many social change efforts don’t explicitly acknowledge these dynamics. After all, it sounds passive. It sounds like saying your strategy is to wait, and that there’s nothing you can do until outside circumstances, beyond your control, line up. Of course, funders often do not want to hear this. Instead, many leaders talk about their work as if it’s meant to create results during a specific period of time. Some of the best efforts play both games: using ordinary moments to advance as they can, while quietly laying the groundwork for the extraordinary moments.

All three of us (Flor, Sol, and Dave) have experienced these moments at different points in our careers. A few years ago, we came together to research them through a series of case studies. We framed these moments as “windows of opportunity” (there are also a few related academic concepts, namely “critical junctures” and “punctuated equilibrium”). We found that activists, government officials, and others we interviewed intuitively understood these moments even if they didn’t have a terminology around them. Many quickly adapted our framing to speak of “micro-windows” within larger “macro-windows” and understood that an open window eventually closes.

It’s worth distinguishing “windows of opportunity” from another phrase that’s become popular in US political discussions in recent years: the Overton window. While the concepts are related, they’re different types of windows.

An Overton window is the range of policy positions that are politically feasible at a moment in time. Picture a spectrum: advancing a policy is easier when it’s close to the center, while anything outside the window on either end is too risky for a politician to support and successfully campaign on. Movements of all kinds aim to shift Overton windows in different ways. Common approaches include staking out extreme positions to pull the window toward your preferred policies; caricaturing an opposing position as being too extreme (that is, outside the window); and highlighting the failures of the status quo to expand voters’ willingness to look for new solutions.

If Overton windows are conceptual spaces, then windows of opportunity are moments in time when those spaces are most malleable. So naturally, another approach to shifting an Overton window is to open a window of opportunity: by creating a sense of crisis or winning a surprise election victory, for example, you can shake up expectations and turn new possibilities into new realities. However, that’s easier said than done. Much more commonly, opportunities are created by circumstances outside anyone’s direct control, like when the Abramoff scandal opened new possibilities for Congressional ethics reform.

Consider how the COVID-19 pandemic changed expectations across multiple issue areas. Many organizations faced hard choices, but many also saw new opportunities. The medical response created new space for organizations advancing Medicare for All, the economic shutdowns moved direct support to workers into the spotlight, and school shutdowns sparked new conversations about the challenges facing caregivers. Operationally, remote/hybrid work led some organizations to distribute their teams geographically. It also forced overdue conversations on how people collaborate and how they’re included or excluded.

All these changes have involved or led to shifts in Overton windows, even if they haven’t (yet) led to durable changes in policies or practices. That’s the crux of how these two different types of windows relate: windows of opportunity create temporary space for shifting Overton windows; those shifts can be translated into real change—if the moment of opportunity is seized.

Cyclical Versus Linear Time

The COVID-19 disruptions were unique. But there will be others. Therefore, it may not always be helpful to think about a single window of opportunity, but rather an opportunity cycle. In our research, we outlined a model that starts with a status quo period, during which the possibilities are less fluid; this is disrupted by a triggering event, leading to an open window of opportunity; the window eventually closes as the status quo returns, until the next triggering event.

This requires movement leaders to think, plan, and act in cycles. People do this naturally in some contexts: the cycles of day and night, the change of seasons, lunar cycles, tidal cycles, menstrual cycles. However, in professional settings, cyclical thinking is less common. The pressure is to frame change efforts in linear terms. It is common to talk of “progress” as moving forward. The arc of the moral universe, in the famous Martin Luther King quote, bends toward justice.

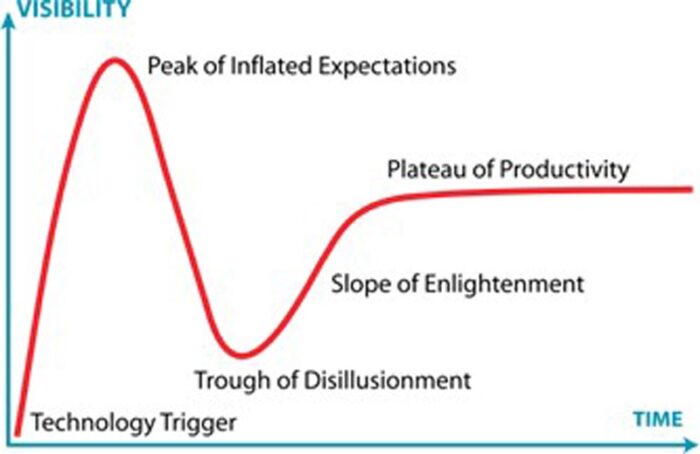

There are some frameworks that describe change in terms of cycles. One popularized by the research firm Gartner is the technology hype cycle. It charts how a new technology moves from early development, to generating inflated expectations for how “world changing” it might be, before then crashing down in the “trough of disillusionment” as we realize its limitations and drawbacks, and then finally finding its way to the “plateau of productivity.” Each year, Gartner releases an update to the diagram, moving emerging technologies along the path.

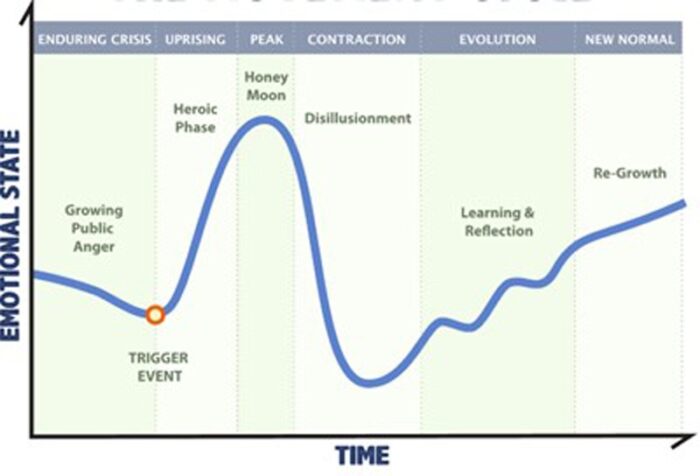

The Movement Cycle, created by the Movement Netlab, follows a similar shape. It charts “emotional state” over time, as an enduring crisis hits a trigger event, leading to an uprising and heroic phase, followed by disillusionment, and eventually learning, reflection, and regrowth. We see this cycle with social movements like the Movement for Black Lives: Black lives are under near-constant threat of state violence, but it’s specific events like the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 or the murder of George Floyd in 2020 that set off wider protests.

Both cyclical graphs are pictured below:

Figure 1: Gartner’s Technology Hype Cycle

Figure 2: Movement Netlab’s Movement Cycle

Ultimately, cyclical and linear time are complements. Yes, time marches forward, but it zigs and zags. Yet the path isn’t random. Certain shapes and patterns recur. There’s an ebb and flow in the openness to change (or lack thereof).

Given that opportunities come and go, organizers can work throughout the cycle and build on moments to create change. The question isn’t whether there will be another opportunity, but rather how we can best prepare for it.

Building Ideas and Relationships Before the Next Opening

Leaders can prepare, first, by setting up ideas of how to shift an Overton window before an opportunity opens. When a crisis hits or the context rapidly shifts, a new idea can add to the anxiety. But a familiar idea, even if it wasn’t accepted before, can be comforting. Milton Friedman called these “ideas that are lying around.” Friedman said his aim was “to keep [ideas] alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.”

The question isn’t whether there will be another opportunity, but rather how we can best prepare for it.

As a libertarian economist, the ideas Friedman liked to see lying around don’t align with our own. But he was right about the value of being ready. Some of these ideas might come out of think tanks or academia, but artists and culture producers are also potent sources. By expanding imaginations during the regular moments, new ideas can be ready to shift the mainstream when the opportunity presents itself.

Movement activists refer to this as “keeping the spark alive” until it can get the air it needs. In 2022, a month after the school shooting in Uvalde, Congress passed a set of policies that survivors and advocates had been demanding for years. The bill enhanced background checks, closed the “boyfriend loophole” for domestic abusers, funded state-level “red flag” laws, and more—an underwhelming response to an unspeakable tragedy, yet still the most expansive gun control legislation passed in three decades.

What works for societal-level change also works within organizations. For example, if a nonprofit already had ongoing diversity and inclusion work in place before the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, then it was much more likely to advance that work in the new climate than if it started from scratch that summer.

Another way to prepare for openings is to build networks and relationships. Together, a network of trusted partners can share information, make sense of a dynamic situation, and seize opportunities. Building those relationships after a window opens is hard. Once things are moving quickly, you call whoever you already know and have less time to build deep trust with new partners.

We also prepare for future openings with the stories we tell about past ones. For example, frequent scandals risk creating a public perception that politicians are all irredeemably corrupt. Not only is this sometimes the unintended result of campaigners’ chosen framing, but it’s also a story often told by antigovernment libertarians like Friedman. Aspiring authoritarians leverage this narrative too, as Trump did when he claimed, “I alone can fix it.”

Windows of opportunity are contested moments, with not only potential upsides but also high risks of negative outcomes. To counter other agendas being advanced in those moments, we can plan our narratives and framing before an opportunity comes: on corruption, recent research from the US, Brazil, and North Macedonia suggests emphasizing structural responses or “guardrails” rather than punishment of individual corrupt actors.

Preparing for the next window means building ideas, relationships, and narratives that might not yield immediate outcomes. These practices are often part of field-building and ecosystem strategies, but they aren’t as common as they should be.

All too often, organizational plans are developed that suggest a linear path . . . this makes planning easier but is strategically damaging.

Cyclical Thinking for Organizations

Changing practices requires confronting the structural constraints on nonprofits and other movement groups. Often organizational plans have no connection to opportunity cycles: instead, organizations focus on annual planning and budgeting, or multiyear cycles of grantmaking or strategy. These rhythms create organizational efficiencies at the cost of context fit.

Some of the savviest activists weave both types of cycles together, but they tend to be the exception. All too often, organizational plans are developed that suggest a linear path to impact after a given number of years. Program evaluations and strategic reviews are scheduled several years down the line, at the end of an organizational cycle. All of this makes planning easier but is strategically damaging.

How can internal organizational cycles be better aligned with external opportunity cycles? Some foundations have introduced “rapid response” grantmaking mechanisms, but that’s still a reactive approach. It also relies on a budgetary autonomy that their grantees lack. Multiyear general operating support can provide space for organizations to plan for the next opening, but there’s no guarantee that they will. Encouraging that thinking requires additional changes.

One important step is to incorporate strategy and planning practices that consider how the context might change. Methods like scenario planning can help organizations expand the questions they ask about the future, from “What are we trying to achieve?” to include “How might our context evolve or rapidly change?” and even “How can we be ready for those changes?” Applied political economy analysis can help probe changes that might occur following an opening by highlighting unstable political alignments or potential allies (part of what are sometimes called “political opportunity structures”). These questions can and should be explored with allies to build a better understanding of what’s changing and strengthen the relationships that will be needed when an opportunity comes.

Finally, these questions should be revisited often. Cycles of learning and adaptation need to run faster than the typical five-year strategy process. It’s fine to set vision and identify a long-term strategy horizon. A long horizon is important to build from one cycle of opportunities to the next. Major investments in research, physical infrastructure, or even relational infrastructure (like building new sectors of work or networks of actors) could take a decade, so planning requires a similar horizon.

However, it’s important not to confuse the strategy horizon with the strategy cycle. A strategy can have a five- or even ten-year horizon, but the cycle of revisiting it should be much shorter. How often you revisit the strategy depends on the volatility of your context.

When you do those reflections—whether you call them “strategy reviews” or “refreshes” or something else—you can also push back the horizon. So, if a group’s 2023-2028 strategy gets reviewed in 2025, push the end date back and make it a 2025-2030 strategy, rather than adhere to the standard practice of waiting until 2028 to set a new strategy for 2028-2033. The only good reason for this practice is the illusion that world cycles can reflect organizational cycles. In reality, it should be the other way around.

In short, change is too rapid for anyone to imagine that movement work can be linear and predictable. Of course, planning is important. But if planning is more flexible and considers how opportunities might shift, then nonprofits and movement organizations can better prepare for moments of opportunity when they arise.