This article is the fourth in a series of personal essays that NPQ, in partnership with Tony Pickett of the Grounded Solutions Network and Marcus Littles of Frontline Solutions, is publishing in the coming weeks. Titled Black Male Leadership: Nonprofit Voices, Truth, and Power, the objective of this series is to lift up Black male voices to highlight the challenges facing Black male leaders in the nonprofit sector, as well as the sector as a whole, amid ongoing anti-Black violence and the disparate racial impact of COVID-19. You can read prior entries here, here, and here.

There is nothing scarier to white supremacy than a Black man (or, for that matter, a Black woman) in power. This is not a theory. Black CEOs make up only one percent of the Fortune 500. In Atlanta, nonprofits led by Black men received only seven percent of COVID-19 Relief funding, but the Black population of the city is more than 51 percent and we’ve had Black mayors for more than 45 years!

Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) have produced generations of Black male leaders who have contributed to the progress of the country and the world. Since the Civil Rights movement, of course, many Black men have risen up out of white-dominated institutions too, although HBCUs continue to make a disproportionate contribution to Black male leadership.

The leadership offered by Black men continues to expand. But the contribution of Black male leaders—that real, fearless leadership—in many ways is seen as more of a threat to the status quo than a contribution to the betterment of society. We see the ramifications of this threat in the assassination of our leaders both literally and figuratively, and in the disproportionate number of Black men incarcerated, gunned down by police, and marginalized in corporate America, among nonprofits, and in philanthropy.

According to Bridgespan’s report, Racial Equity and Philanthropy: Disparities in Funding for Leaders of Color Leave Impact on the Table, 92 percent of foundation presidents and 83 percent of full-time staff members are white, while the majority of the work of foundations and philanthropy is built and funded off of the pain of Black people. Similar data have been found in the nonprofit sector as well, as reports from both the Building Movement Project and BoardSource illustrate.

Black suffering is so often fuel to the nonprofit sector, but our intellect rarely guides it, let alone benefits from that sector. It’s the same old story. Black labor builds America, but Black labor profits very little.

I never got into the nonprofit arena to get rich. I was called to this work after tiring of seeing others profit from my work, and after witnessing far too much Black suffering. I started the Partnership for Southern Equity over a decade ago to cultivate an environment where our team has the ability to bring their full selves to our work while lifting up the communities that we love so dearly.

And that’s what I want for any Black man stepping into this work—a chance to be fully who you are, so you can show up with character and authenticity and can do what you were called to do. While my intentions are good, I’ve learned over the past 10 years that it takes more than just vision to realize this dream. It takes hard work, dedication, humility, courage, and faith. As a Black man, you need all of that when you take a stand for what’s right, especially in light of COVID-19 and the multiple uprisings across this nation against systemic racism.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Many months into the pandemic, a month after the injustice handed down in the Breonna Taylor case, and weeks after a new federal government attack on critical race theory training was launched, now is the time for the vision that I and others like me share to become a reality and engage Black men throughout the nonprofit sector. This is the time where our intellect is honored just as much or more than our labor. This is the time to shape a new way forward that is inclusive and honors Black women so they too are not seen as revenue generators or communications tokens for nonprofits.

This is also the time for old Black male leadership to not be intimidated by young leadership. Since the beginning of slavery, Black men have faced an insidious complex—the magic Negro—being the “onlyest” one that white people and the Powers That Be turn to. This complex has worked its way into how nonprofits, foundations, and philanthropy are designed, when you only see two or three Black men in an organization at a time. While some have used those positions to help, historically many in those positions have oppressed the rise of young Black male leadership by sticking around too long. I get it, you’ve arrived, but what about those who are coming after you? Young leaders are building on the work of the senior leaders who have come before them. They are not coming in to make senior leaders irrelevant. That’s the lie that white supremacy has sold us for hundreds of years. It is time for legacy Black male leaders to shift their thinking from the fear of irrelevancy to becoming the harbingers of collaboration and healing.

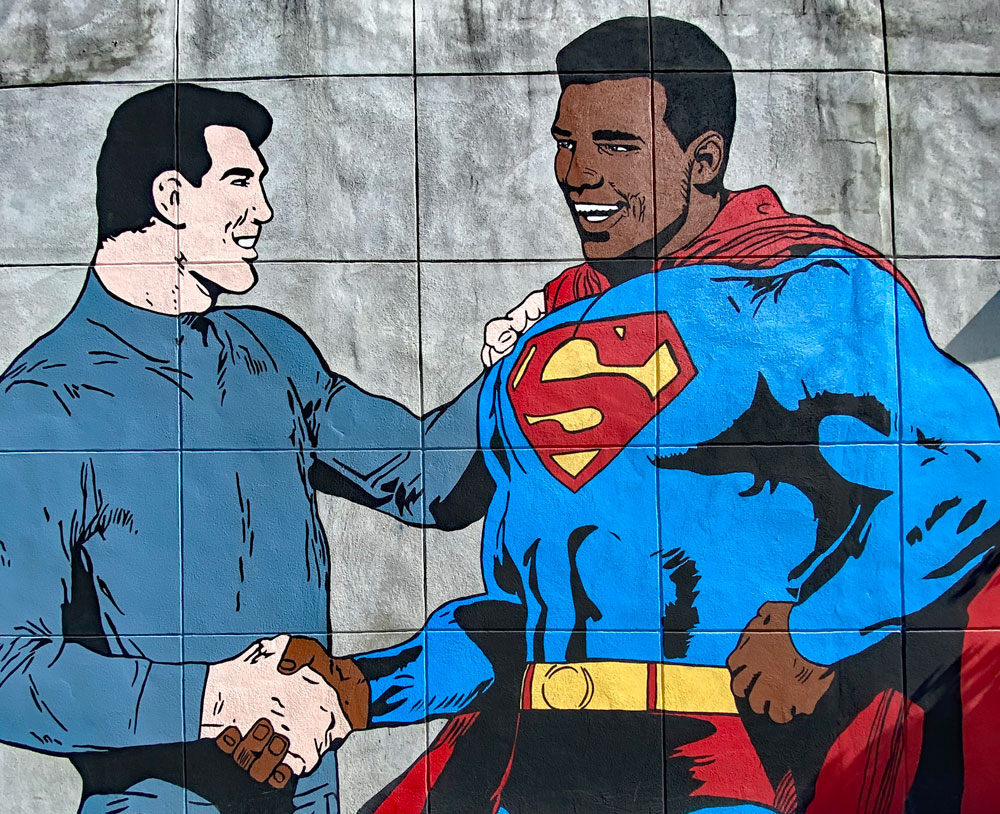

If our leaders of old have taught us anything, it’s the need to take care of ourselves in this work. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Dr. Joseph E. Lowery, and Congressman John Lewis were looked at as superhuman because they were not allowed to be human. They carried the burden of leadership, especially in their physical bodies, and while Dr. Lowery and Congressman Lewis held on until this summer, we lost Dr. King and so many others before their time. The recent passing of our friend and colleague, Cecil Corbin-Mark of WE ACT for Environmental Justice, at the young age of 51 was a particular shock. The reality is that Black men in the nonprofit world are dealing with the effects of this time the same way our Civil Rights forebearers did—by trying to be superhuman. But this time is different. Perhaps better said, it is incumbent on all people of good will to ensure that this time is different.

COVID-19 and the uprisings have created an opportunity, even amidst the considerable suffering. We know that the novel coronavirus has taken a disproportionate toll on Black Americans. The best available estimate finds, as of October 13th, a mortality rate of 108.4 people per 100,000, twice the mortality rate suffered by white Americans.

And yet, even amid the pandemic and its devastating health and economic consequences that have affected so many families, Black men must take time to heal. This long-term, generational work is not easy and requires stamina, but it also requires the ability for Black men to fail forward, love people, and not be expected to do superhuman things with a minimal amount of support. This work requires Black men to embrace a different kind of leadership—to free ourselves from the shackles that have held us back, but with full knowledge of the broad shoulders that we stand on. It also requires a system that allows Black men to be human beings and not just pawns to advance a mission.

Finally, while I can sit here and shake a finger at the system, there are also some steps we as Black men in nonprofits can take to realize a better world for ourselves:

- Take the time to work on your character, instead of how much money you can raise or how eloquently you can state the issue. Live the sermons, rather than just giving them; we don’t have time for leaders who can be felled by a lack of humility.

- Amplify and elevate Black women in leadership. In order for Black men to be whole, we have to work for Black women to be whole too, because we must support each other to move forward as a community.

- Stand for honesty, integrity, and your humanity. Don’t be afraid to lose a job or funding for telling the truth and for being bold in forcing the environment that you work in to allow yourself to be human.

- Take care of yourself. Practice taking care of your body, mind, and spirit.

The journey ahead is not a simple one. But one thing we know for sure: Leadership is not about heroism, but rather doing the work—it is about following as well as leading, feeling as well as thinking, listening as well as talking.

In short, we can no longer tolerate the continuation of a fatalistic narrative that a Black leader has to be a martyr in order to be venerated by society.