These times are unusual, and not just because of COVID-19. What distinguishes this time from others is that we are truly seeing the culmination of an entire system that is at odds with the people it should have been designed to serve. What remains unknown is whether this will be the moment to usher in a 21st-century civil rights movement or a new civil war.

What will make the difference in these two starkly different visions of the future?

The past four years should be a wakeup call for everyone in this country. Donald Trump did not just happen; he is the product of over 400 years of white supremacy and decades of deepening investment and organizing by the far right. Whether he’s reelected or not, there is a long road ahead for America. Our courts are stacked, our civil liberties stripped, our institutions racist to their core, and our political institutions corrupted by corporate rule. This is not a nightmare we will just suddenly wake from. After three-and-a-half grueling years, what’s the strategy? Outnumber them? Outvote them?

Those of us who strive for social justice must step into the breach, deeply reflect upon and analyze how the right has been out organizing us, apply a critical lens to our own movement, and think outside the traditional box of organizing. If our goal is to actually make real and lasting change, we need to meet people where they are and not apply litmus tests that force us into an us-versus-them binary.

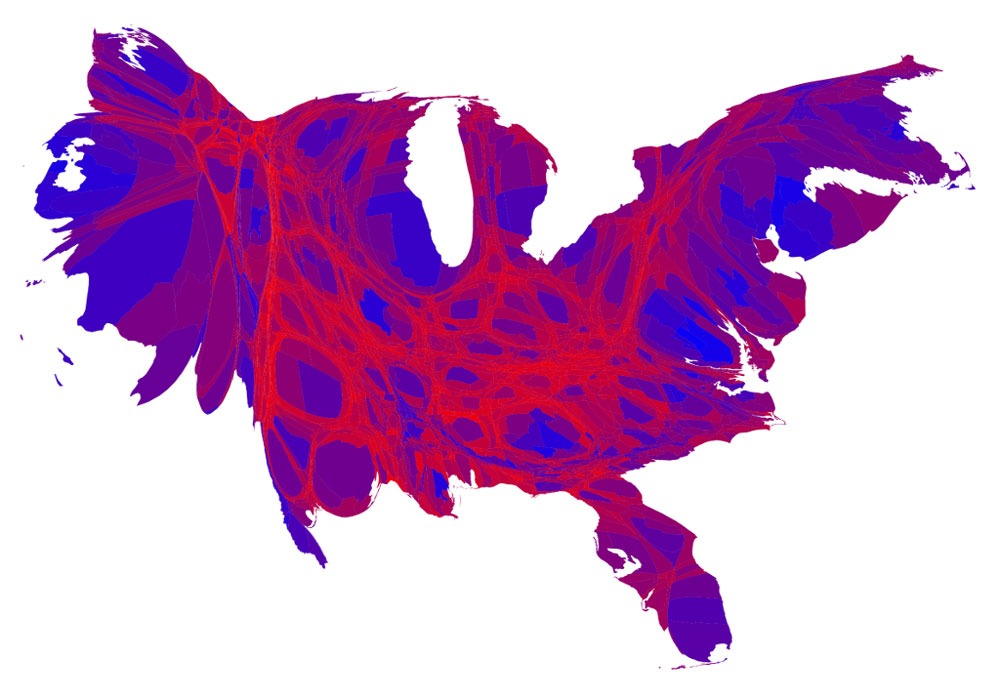

This is not a fight that will be won inside the Washington, DC beltway. Rather, it is one that will be determined by reinvestment in social justice organizing in rural places, on the ground, and in local communities across the country. And what this requires is really talking to people in rural communities about their lives.

When those kinds of investments are made in rural places, the effect is profound. From the Deep South to places like where I live, in Idaho, having deep conversations with people and meeting them where they are has become one of the most powerful strategies for interrupting escalating White Nationalism and accelerationist hate groups. By talking about shared issues and values outside the boundaries of political affiliations and offering an analysis rooted in compassion, advocates for a racially inclusive America can build the kind of infrastructure needed to unite rural, suburban, and urban communities in a shared struggle.

It is not acceptable to stand by while others see this as an opportunity to exploit the pain people are feeling to further divide and polarize us. Philanthropy, nonprofits, and movement activists have to rethink our organizing strategy and use every opportunity in our midst not to restore, but remake and re-envision what a healthy democracy can look like and deliver. To organize in this moment requires remembering that success is only lasting when no one is left behind. Our freedoms are bound together. This crisis has revealed the deep cracks and the places where we must go and grow.

The impermanence of our democracy is in plain view, but how the country arrived at this moment is more obscured. Organizers have been sounding the alarm about progressive divestment in rural America since the Great Recession and even beforehand. That void was quickly filled by alt-right and extremist hate groups, who intensified their efforts in rural areas across the country. The events of 9/11 and the subsequent targeting of Muslim populations provided an opening that over time allowed extremist groups to gain power and funding to revamp their organizing efforts.

By exploiting the economic struggle and personal pain of the poor and working class, hate groups are offering people an analysis that not only offers the cause of their problems but also the antidote, albeit one steeped in bigotry and fear. Beyond organizing communities, they have groomed candidates to run for office and successfully elected local and state leaders to represent their interests and advance some of the most draconian legislation ever introduced.

The alienation of people from their government was no accident. The two-party system makes it easy to divide the country up into ideological camps. The lack of investment in political education helps create a voting public with very few tools to critically assess policies and their implications. All you have to do is choose your camp, and “your representatives” will do that work for you. Alignment with a political party has little to do with the policies they espouse and much more to do with the political identity they choose, or their parents or grandparents chose. While barely recognizable today, the Republican Party still enjoys the paternal authority over its members.

The architecture has long been in place to entrench a white nationalist agenda in practice and policy at every institutional level. The advent of Trump’s election exposed years of investment. Every subsequent day of this administration has revealed the degree of power that has been seized and now threatens the future of our democracy.

It wasn’t as if the plan and its implementation were happening out of view. It was painfully obvious how it was unfolding. While the progressive movement was in a constant defensive fight, the right has been hard at work grooming, funding, and electing governors, state lawmakers, and congressional members. It didn’t matter if the bills presented surpassed the boundaries of rational thought and governance; that wasn’t the point. It didn’t matter if legislation that was passed at the state level was constitutional or not; the endgame was a court system and a Supreme Court of their making that would ultimately determine the success of these efforts.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Under Trump, 200 conservative judges have been appointed, including two appointments to the Supreme Court. With the escalation and rise of hate groups, their architects and leaders now occupy some of the most important positions in government, courts, and institutions. This will remain a great threat to our democracy, one that will remain long after the election of 2020.

Pushed in part by philanthropic divestment following the Great Recession, the social justice movement has increasingly shifted focus to urban centers, lobbying and persuading lawmakers from states with a high density of people who could pressure them to take action. The immediate impact superseded the long-term systemic organizing that could unite urban, suburban, and rural communities around a shared set of issues and values, offer a different political and social analysis, and build power for the long-term. And the stage was set for a coordinated and deliberate effort by the far right to seize control of rural states.

The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) became a leading mechanism for the Koch brothers to manufacture model legislation, groom state legislators, and introduce a myriad of bills across the country that would roll back civil liberties and introduce authoritarian forms of state and local control. Targeting red states, often with a trifecta government in place (i.e., both houses of the state government and the governorship), bill after bill was introduced and passed, while Democrats and progressive organizations poured all their energy into defeating them.

Whether successful or not, the effect was that these policies reflecting the world order view of people like the Koch brothers started to become normalized in the hearts and minds of their base. Bewildered progressives and Democrats scrambled to produce language that would move their agenda forward, vetting, and testing—trying to figure out how to organize and mobilize a base of opposition.

It is also not inconsequential that the political system and the subsequent organizing efforts of the left have been operating within a dialectic of good vs. bad, right vs. wrong, identity vs. identity. Nothing could be more advantageous to the extremist right-wing mobilization than to continue down that path. Yet it seems social justice groups are often unable or unwilling to apply the same scrutiny to our own movement that would allow us to grow, expand, and become more relevant. If that seems harsh, it is intended to be. It is also not entirely the fault of the left movements who, out-funded, became beholden to philanthropy—a relationship that until recently has been toxic and directed the work of organizations to a piecemeal, siloed model that stretched their board members a bit but was never intended to create systemic, institutional change that would be threatening.

In order to remain viable, organizations needed to meet the metrics and deliver the results determined by the very people who have been the beneficiaries of a system of inequality. Both in the midst of changing demographics and board compositions, the crisis of the pandemic may provide a new opportunity for a 21st-century civil rights movement.

Philanthropy itself must be considered because one can find different foundations on very opposite sides of the same coin. While fewer foundations exist on the right, they have concentrated their wealth to advance a shared agenda that uses policy as a tactic rather than a strategy, while the nuance of philanthropic funding on the left is spread across an untold number of causes, and projects often aimed at specific policy wins that deconcentrate the impact.

Since 2008, the right has long been investing and funding leadership development for youth organizations in a way that far outpaces more liberal foundations. As of 2008, the ratio was two-to-one. By 2014, it was three-to-one. Too many so-called progressive foundations forgot—or perhaps never understood—that investing in people is what drives the work.

Fortunately, some of these more liberal foundations are starting to make the shift to trust-based philanthropy that honors the time and investment of people who have been giving of their time and labor in their own communities to make change and moving to a system that invests in leadership development and the operating expenses that are needed to carry out the work at hand amidst the barriers. Recently, 40 organizations made a pledge to engage with grantee partners to generate thoughtful and immediate responses that will serve affected communities.

It is a welcome shift in culture. Whether the pledge will be fully embraced to meet the challenge will depend on changing the culture of philanthropy, one that makes the transition from tactics, compliance, and regulation to one that makes the kind of long-term investment that is rooted in real partnership and builds upon the experience, skill, and forward-thinking of those dedicated to change and those leading it.

As economic depression looms, we cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of 2008. The philanthropic sector cannot afford to divest from progressive organizing in the places where hate lives, thrives, and is driving our national politics and the future of our nation. To change the trajectory and organize people around a race-conscious, working-class agenda, organizing in rural communities must be a priority. Never again should philanthropy, movement leaders, and nonprofits cede power to the far right by defunding the social justice efforts in the places we now understand are critical to our collective liberation.