When John Winthrop and the Puritans arrived in Boston in 1630, they set out to build a fort to protect themselves from the natives, the Spanish, and the idiosyncrasies of the very land for which they had risked their lives. To commend the event, Winthrop wrote and delivered a rousing call to action, to build a “city upon a hill” that would shine its light of benevolence on all within sight. From this modest fort, a paternal empire of efficiency and benevolence would spring.

While it may be a stretch to draw too many parallels between modern-day information technology (IT) departments and a group whose idea of document security was a wax seal, there’s actually some commonality.

Like the Puritans, IT arrived late to the scene and well after an average organization’s other inhabitants had carved out a niche in an already crowded org chart. Where John Winthrop sought to bring civility to the wilds of New England from his fort, most IT departments are structured to bring order to the chaos wrought by unruly staff, clients, and stakeholders. From their forts, they hope to shine the light of efficiency and order on the rest of the organization.

Most important: to grow, the Puritans had to embrace populations of immigrants with their own ideas about what it would mean to build that “city upon a hill.” Similarly, IT departments now face an influx of needs to which they must be receptive if they’re going to help their organizations become more efficient and more effective.

As new technologies such as cloud computing, shared infrastructure, and collaboration enter the workplace, IT departments must be prepared to adjust. While historically IT has largely enabled operational efficiency, today’s IT workers should focus more on strategic goals, such as enabling organizational mission. While some IT workers have resisted these changes in the name of organizational security and control, the shift has already begun to take hold. As these changes continue to permeate the workplace, IT can best secure a place for itself by embracing its new role as strategic enabler, not by resisting the change.

When IT departments first arrived, they were agents of efficiency. We networked computers so that files could be shared, set up servers to store and back up data, and learned how to perform that most revolutionary of time savers: a mail merger. Efficiency was the hallmark of a good IT program, but efficiency rarely goes hand in hand with flexibility.

Efficiency requires standardized processes and common systems. That’s why so much of IT work involves documenting how things get done and then choosing hardware and software that support those processes. It’s why your IT department will support the BlackBerry but not the iPhone, or all Macs but no PCs. Standards make organizations more efficient;? exceptions slow us down. Over the years, IT staffers have been trained to despise exceptions, those scourges of efficiency, and cherish their systems. They are defenders of rationality and time well spent.

Over the past five years or so, however, a flood of digital immigrants has arrived on our shores. Computers have gotten smaller, and the Internet has become more pervasive. Technology is no longer confined to our offices. And as nonprofit staffers have become more tech-savvy themselves, they’ve pushed IT to move technology out of the fort and into the field: the marketing department, the fundraising department.

Here’s how Peter Campbell—the IT director at Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law firm in Oakland, California—sums things up in “The ROI of Flexibility”:

Without standardization, automation, group policies that control what can and can’t be done on a PC, and some protection from malicious web sites, any company with 15 to 20 desktops or more is really unmanageable. The question is, why do so many companies take this ability to manage by controlling functionality to extremes?1

What’s the role of technology and the IT department when tech can’t be confined to the fort and your staff, clients, and stakeholders are knocking at the gates?

Today’s technology has to serve a dual role: to maintain efficiency while also building effectiveness. Ed Happ, now the CIO at the International Red Cross, saw this coming early in his days at Save the Children. Happ watched field staff members create their own technology solutions to meet the needs of their communities regardless of the systems IT had put in place. His IT staffers, meanwhile, were so focused on the efficiencies they could control that they didn’t have the bandwidth to support that innovation in the field.

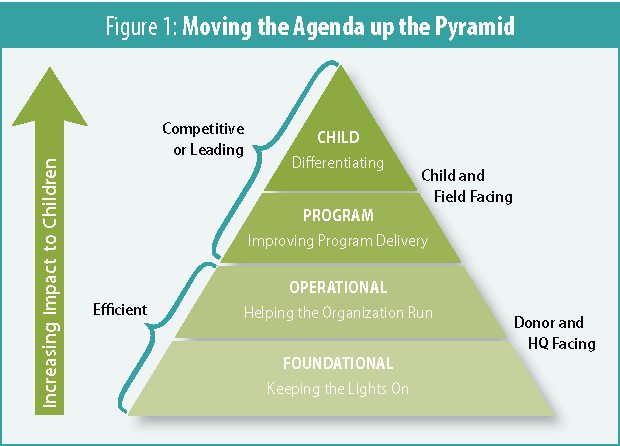

Save the Children is not the only organization that has faced this dilemma. As Happ surveyed his peers and colleagues, he realized that he could represent the IT function at every organization, large and small, as a pyramid (see figure 1, at right).

In Happ’s pyramid, the more IT resources—time, money, and staff—spent in any of the four areas, the larger its representation. Time and again, Happ discovered that organizations spend most of their IT resources on efficiency builders at the bottom of the pyramid: e-mail management, server maintenance, and help desk–related tasks. But for Happ, maintaining efficiency should not trump serving children;? and when it does, there’s a problem. He came to believe his role was to use technology—and the IT department—to serve the mission of Save the Children.

It’s a goal we can all agree with, right? As mission-driven organizations, we do various gymnastics to ensure that as many donor dollars as possible go toward our causes. In this way of thinking, the IT department is a money sink, a fort necessary to maintain security and keep order, but not a resource that helps move organizations toward their overarching goals.

But with a shift in the role of IT, this perspective becomes less true. There are tremendous opportunities for nonprofits to shift IT away from keeping the lights on and toward technology that actually serves mission. If we redefine what the IT fort looks like, we can make this happen. So where do we start?

Cloud computing is a technology term that’s been flying around a lot lately, but it’s more than just a catchphrase. It’s a chance for nonprofits, especially smaller organizations, to access world-class IT products and services without needing world-class IT expertise.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While many different definitions of cloud computing exist, it’s a pretty simple concept: software and information that used to reside on your computer’s hard drive are instead delivered, on demand, over the Internet. We most often experience the cloud through applications such as Google Apps, Microsoft Office 365, and Salesforce.com.

Cloud-based software offers several benefits for nonprofits:

- In a cloud model, pricing can better align with nonprofit budgets. Monthly costs per user are easy to budget for and manage, as opposed to traditional software purchases that require a large up-front payment.

- You access the same software as everyone else. When a cloud provider makes a major system improvement, everyone on the system receives the upgrade, not just the big organizations, so everyone wins.

- The cloud is accessible anywhere. Staff that travel or those who work from home or in the field can access software from any browser, even on their phones, saving time and resources—and providing the opportunity to innovate.

- In a cloud model, there’s no infrastructure to manage, nothing to install and keep updated. You don’t need to keep data on a server in the closet that you have to maintain yourself.

That last point is the key: if they don’t spend time installing updates or managing servers, your IT staffers are free to do more important work, such as figuring out how to conduct that annual survey on handheld devices instead of paper, or using mapping software to better understand where your clients come from. As Melissa Zimmerman, an executive assistant at the Arc of the Virginia Peninsula, shares how her organization has moved its e-mail application to the cloud:

The actual transition was labor-intensive, but we’ve spent virtually no staff time updating/?maintaining our e-mail.?.?.?. Moving to the cloud has improved our entire e-mail system because it is now administered by experts, and it has freed up staff time to do what really matters: furthering our mission.

So why isn’t everyone rushing to the cloud? Because of the fort. IT teams are trained to control everything, but cloud services can’t be controlled by an organization’s internal IT staff. IT can’t see or access the machine on which these programs reside, and that is unsettling to some IT departments. As Doug Chamberlin—a programmer, analyst, and database architect at Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program—notes, data security has become a major point of contention. “How can you say you have improved security of your data by storing it at some unknown site and letting a third party’s staff care for it?” he says. “I’m just waiting for a major breach to be traced back to a disgruntled employee of a cloud provider.”

This criticism of the cloud may be true. But for most nonprofits—those with budgets under $250,000 a year and only a handful of staff—Earthjustice’s Campbell suggests that the opposite may be true of cloud security:

About 80 percent of the people I speak with come from that perspective. They value security over entrepreneurship. But it’s a simple equation, especially for smaller nonprofits. Salesforce.com has a slew of security experts guarding your data. You have your IT person, if you’re lucky. You need to look at your own security. If you don’t have strong password requirements and strong firewalls, you can’t beat most cloud providers. You have to evaluate the vendor, but chances are that for most understaffed organizations, a solid cloud provider will be safer.

The cloud is one way for nonprofits to ditch the forts and start building towns outside their walls for their digital immigrants. Nonprofits have also built capacity and focused on mission through technology-based collaboration.

In the nonprofit sector, the term collaboration has reached saturation. Donors ask for it, funders demand it. In 2009, a Collaboration Prize was awarded.2 But we all know achieving collaboration is much more difficult than simply talking about it. In the realm of technology, however, this truism may be the exception to that rule.

Many technology needs are specific to each individual nonprofit. Generally speaking, however, e-mail is e-mail and phone systems are phone systems. Why not collaborate to share technology-based services with like-minded organizations?

Jan Berry, the CEO of MACC Alliance of Connected Communities, a consortium of community organizations, has done more than ponder this question. Over the past five years, MACC Alliance has provided back-office technology to its membership of community-based human-service agencies. IT provides services that nonprofits have traditionally outsourced and shared—such as human resources, facilities management, and finance—but it also provides IT and data management services.

Berry is quick to acknowledge that even as we call for greater efficiency in nonprofits, it’s important to acknowledge their real differences. “One of the interesting things about the efficiency conversation is the assumption that nonprofit businesses are highly similar, but they are not,” she says. Still, even with diverse needs and business processes, nonprofits can share key services such as e-mail and document and data management. Launched with just four organizations, the Alliance carefully crafted services that would meet the diverse needs of the members. Now, it has 15 participating nonprofits.

“Not every one of our members participates,” Berry says. “Some want control of IT in their own building. For some, they’re not of a size where the cost works out for them. Our services are designed for a $2 million to a $4 million operation.”

But for several participating members, the payoff extends far beyond efficiency and cost savings. Several member organizations share a client-services database, despite the fact that they provide entirely different kinds of services. Ten organizations collaborated to find a system that would meet most of their needs and customized the rest. Though the data is stored centrally, each has access to a customized interface, and each agency’s records are protected.

Buying into a software installation and customizations collectively is a great way to save money. What’s most interesting, however, is that in the process of developing and using the database, the groups have begun to craft data-sharing agreements. They have collaborated to develop common theories of change and data tools so that they can report apples-to-apples data to funders and their stakeholders. That’s the sort of change that can benefit the entire sector.

Over the past decade, IT departments have looked an awful lot like that first Boston fort, but digital immigrants have increasingly set up their tents outside the fort walls. Most of these technology workers and consumers hold more computing power in the palm of their hands than our geek forefathers could contain in a single building half a century ago. They have learned to conjugate brand-new verbs like “google” and “tweet.” They want to work at home, on the road, and at 3:00 a.m.

Too many IT departments still act like it’s the fort that matters, unable to accommodate the demands of the crowd outside. As usual, the technology part is simple;? the challenges lie with the human architects. We need to encourage and invest in IT leaders who will protect our organizations, without sacrificing our ability to do what our sector does best: respond, adapt, and create change.

Copyright 2010. All rights reserved by the Nonprofit Information Networking Association, Boston, MA. Volume 17, Issue 4. Subscribe | buy issue | reprints.