January 15, 2019; Fast Company

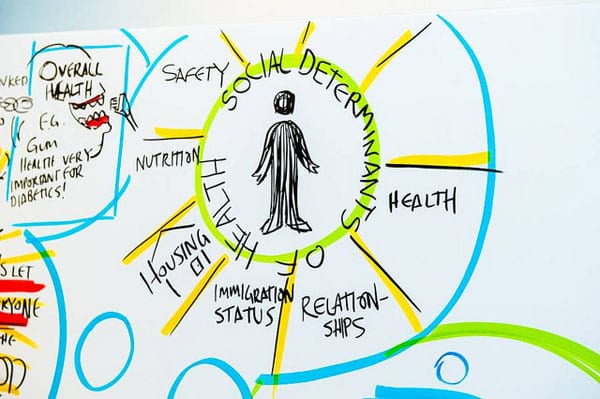

As NPQ has widely covered, evidence has been mounting for some time now that most of the factors that determine whether you’re healthy or not are social in nature, not clinical. These so-called social determinants of health, whether economic, environmental, or behavioral, influence at least 80 percent—by some measures, 90 percent—of health outcomes. At the level of rhetoric, at least, much of the healthcare world has embraced this outlook. At the level of practice, however, progress has been more uneven.

As Gary Young, director of the Center for Health Policy and Healthcare Research at Northeastern University, has observed, “the business model is still one that requires hospitals to fill beds, even if filling beds does little to achieve better health outcomes.”

Slowly, however, healthcare practice is catching up with the science, with a growing number of health systems investing in community loan funds or housing because these investments ultimately keep people healthier—often more so than miracle cures or other alternatives. For instance, last spring, NPQ profiled a Toledo hospital (ProMedica) that partnered with Local Initiatives Support Corp. (LISC) to create a $45 million fund ($25 million in loans and $20 million in grants) to support neighborhood-based economic development. Last fall, NPQ also profiled a hospital in Columbus, Ohio (Nationwide Children’s) that has participated in a decade-long partnership that has invested $22 million in affordable housing to date.

Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest nonprofit integrated healthcare system—with 12.2 million insured members, 39 hospitals, $72.7 billion in annual revenues, and an estimated 217,000 employees—has adopted both of these approaches by setting up a loan fund that focuses on affordable housing. The creation of its $200 million community loan fund, known as the Thriving Communities Fund, was launched last May. This week, it announced its first investments out of that fund. As Adele Peters notes in Fast Company, these investments are:

- The creation, in partnership with the nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners, of a new joint equity fund called the Housing for Health Fund, with a focus on the nonprofit’s hometown of Oakland, California. That fund has committed $5.2 million to help a local nonprofit, the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation, purchase a building in East Oakland.

- The formation of a nationwide loan fund, in which Kaiser and Enterprise are each committing $50 million.

Additionally, Kaiser made a specific commitment to house more than 500 people in Oakland who are over 50, homeless, and have at least one chronic health condition. As Peters explains, “Kaiser worked with a community partner to identify individuals who are particularly vulnerable, and is currently working with community and government partners on the specifics of the plan.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“We have been learning over the years that homelessness and inadequate housing are major health issues,” Bechara Choucair, a physician and chief community health officer for Kaiser Permanente, tells Peters. “We know that safe and stable housing is a key determinant for both physical and mental health. And really, without a place to live, it’s pretty much impossible for a person to take care of their basic health needs.”

The housing crisis, Peters notes, is particularly acute in Kaiser’s home city of Oakland, where rents jumped 51 percent between 2012 and 2017. Between 2015 and 2017, homelessness in the city grew 25 percent. Homelessness in the surrounding county of Alameda has jumped 39 percent.

“If you take an area like California, you have the dilemma right in front of us: On one hand, you have extreme wealth, expensive homes, etc., and on the other hand you have homelessness,” notes Bernard Tyson, Kaiser’s CEO.

Of course, $200 million, although certainly significant, is still a relatively small number for a company with over $70 billion in annual revenues. The hope is that Kaiser can build on its initial investment over time. Kaiser, because of its strong presence, especially in California, is well positioned to test the model, since many people who it serves through its housing investments may well be Kaiser-insured members. This means Kaiser may be able to track how much their health improves. If Kaiser patients stay healthier in their new homes, Kaiser may be able to recoup some—maybe even all—of its investment in reduced insurance payouts.

Tyson tells Peters that as Kaiser becomes more adept at housing, it hopes to apply the lessons it learns nationally. “We have a great opportunity to connect those dots of lessons learned across our markets, across the country,” Tyson says. “There are many other organizations that can do the same thing. And so, if we can offer ideas about how to do that, working with others, then we can serve a bigger purpose as well.”—Steve Dubb

Correction: This article has been altered to reflect updated and corrected information from Kaiser regarding its investments.