August 1, 2016; Washington Post

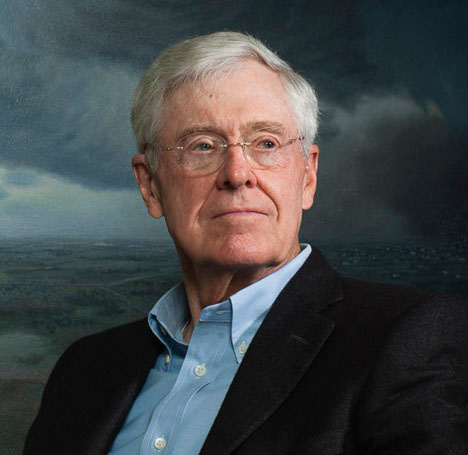

Twice a year, the politically powerful Koch brothers convene a large gathering of conservative mega-donors to target hundreds of millions of dollars into political campaigns. Their focus has been to support candidates and policies that support a small government, almost libertarian philosophy. At this gathering, strategies to oppose and repeal the Affordable Care Act have been developed and funded. From this network, support of Mitt Romney’s effort to defeat Barack Obama’s reelection was developed. Their approach to dealing with poverty has adhered closely to the Reagan-era focus on lowering taxes on the rich so that the poor would be helped through the “trickle-down” effect. Direct action by government to cure societal ills was anathema to the Koch approach. From afar, it seemed that the pain of poverty was not a topic on their agenda.

But this year’s convening, which began only days ago, seemed remarkably different: “As top network officials and supporters met at a sumptuous mountain resort here this weekend, there was one dominant focus: the yawning gap between America’s privileged elite and working class.”

Charles Koch has long been concerned about the threat of the U.S. becoming a “two-tiered” system. For the last year, he’s expressed a desire to find a way for individuals to succeed economically without “gaming the system” while still ending government overspending. Perhaps scared by the successes of the Trump and Sanders campaigns in mobilizing the anger of those who see the economy as structured to make the rich richer, the Koch network appears to be shifting its focus from Washington politics to “intensifying its investments to support communities, schools and the family structure.”

Brian Brenberg, a business and economics professor at The King’s College, gave his perspective on these present challenges:

Unless we address these underlying issues, these underlying threats, candidates, elections—they are only going to become more extreme and more divisive. Because if history has taught us anything, it’s this: When a citizenry feels neglected and ignored, they will line up behind leaders who give voice to their concerns and promise relief for their problems—even when the eventual outcome is likely going to be far, far worse.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Having recognized that economic inequality is a real issue and a threat, will they change the solutions they support? Will they be ready to rethink the role government should play to level the playing field? Or will they take the power of their huge resources and use it to support policies and programs that go further down the policy road they have traditionally advocated?

Reports emerging from their gathering don’t leave much hope that they see the current situation as a failure of their strategy that necessitates a new approach. Charles Koch’s diagnosis of our current situation seems to be that our problems come from not being libertarian enough: “Unless we make progress here in our culture, we are doomed to continue to lurch from one political crisis to another, and we will likely degenerate into socialism or corporatism, as two-tiered societies typically do.”

Without a 180-degree turnaround, the Kochs’ political muscle will be put to work to further reduce government programs that directly help the poor and reduce tax levels. Rather than learning from their experiences, their bet is that the recognition of a real threat from a dissatisfied body politic to their personal well-being will motivate the private sector to do more and be more effective than they historically have been. Perhaps fear will prompt an increase in charitable contributions or more private investment in job-creating activities, that by their way of thinking will help narrow the gap between rich and poor.

That these programs have not proven successful does not seem to be causing any rethinking. Economist Paul Krugman described this phenomenon as he viewed the current thinking of trickle-down economists.

What strikes me is the contrast with the 1970s. Back then, the experience of stagflation led to a dramatic revision of both macroeconomics and policy doctrine. This time, far worse economic events and predictions by freshwater economists far more at odds with experience than the mistakes of Keynesians in the past seem to have produced no concessions whatsoever.

If this describes what we will see from Koch politics, we are facing a well-funded battle over solutions to meet the needs of the poor.—Martin Levine