Editors’ note: This article is from NPQ‘s winter 2022 issue, “New Narratives for Health.” In this conversation between Cyndi Suarez, NPQ’s president and editor in chief, and Kaytura Felix, Distinguished Scholar, Department of Health Policy and Management, at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health—and founder of the podcast Griotte’s Beat: Speaking Truth, Finding Justice—the two leaders discuss medical racism, health justice, and what it really means for a system to support people’s health.

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

Cyndi Suarez: Thank you so much for taking the time to have this conversation with me, Kaytura. There is a lot that I want to dig into about your work, starting with something you said in an address at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Interdisciplinary Research Leaders fellows’ event. You said that you chose to become a doctor as a child growing up in Dominica and seeing inequities there. And I’m wondering if you can take me back to that time and paint a picture of what that little girl experienced and how it started you on your professional trajectory.

Kaytura Felix: That little girl saw a lot. And she saw a lot in a place where the mantra was that children should just be seen and not heard, right? My mother was a teacher; she taught in rural areas, and during the week we lived in a small hamlet in the mountains of Dominica—mother, father, three kids, and a housekeeper, who traveled with us. And I remember my father dropping us off at a clinic because my brother had some kind of skin infection on his ear. We walked into the building, and there was a bunch of doctors’ offices there, and she picked up the phone in the hallway outside the doctor’s office and said, “Dr. McIntyre, I’m here.” She then put down the phone, and we walked right in. The interaction took maybe five minutes. The doctor looked at my brother, wrote a prescription, and handed it to my mother, and we walked out. And when we were outside the building, she realized that she hadn’t paid him. So, we went back in and she called him again. And after a brief moment, she walked back into the office, trailed by her three children. There was an exchange of money—it was probably about fifteen dollars. I knew it was a lot of money. When we walked out, I noticed that there was a bunch of people waiting to be seen. They were poor, they were Black, and they were from the rural villages. They looked dusty and tired. It was between eight and nine a.m., and they had probably woken up at three o’clock in the morning to get to the doctor’s office, because the roads were bad. They would have had to drive long hours to get into the town. Even then, I understood that they were low down on the hierarchy within Dominica. So, after that transaction, I said, “Mammie, what happened there? Did you pay the doctor?” She said, “Yes.” “How much?” I asked, and confirmed the price. And I said to her, “Mammie, that’s a lot of money. How are those people, those poor people in there, going to afford to pay that kind of money?” And she was silent. And I said to her, “Mammie, when I grow up, I’m going to become a doctor. I’m going to become a doctor and provide free care.”

CS: And how old were you?

KF: Eight. And I kept the spirit of that stance. I went to medical school. And what has always been important to me is what happens to those on the margins. I was a financial aid student in medical school. I got grants, I got some scholarships. And you had to write thank you notes to your benefactors about the things you cared about. What I cared about was poverty, poor people, and those on the margins—those with less material resources. And that has guided my work. It guided me when I was an undergrad, and in medical school. It has also guided the choices that I’ve made—going into general internal medicine and then into research. I practiced briefly, but I realized that taking care of patient after patient wasn’t where the action was for me. I never practiced in Dominica. I immigrated to the United States in the mid-1980s, living on the East Coast. My undergrad years consisted of two years at Hillsborough Community College and then two additional years at the University of Florida. And then I went to [Weill] Medical College, Cornell University, in New York City—and I did a residency at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. Then I did more studying at the Johns Hopkins schools of medicine and public health. But when I saw patients in Washington Heights, in New York City, Black and Brown people would come in about their blood pressure—they were worried about the

violence in their communities, they were worried about their grandchildren in jail. It was the violence in the streets, it was the family problems they were having, that consumed them. These are the things people brought to their healthcare providers. And there was no time for that. It was in and out. So, what I’ve been really concerned with is working upstream—just going as far upstream as I can so as to go deeply into the system and see what affects people. I mean, every part is important, but that’s the part that I most care about. Upstream is where small, just actions can have big impacts on many people.

CS: You’ve been a leader in this work for a long time, probably even before people were really talking about health justice in quite this way. It seems like you were seeing this landscape before it became what it is now: a field that people study in health justice. I noticed that you have held different roles within the Health Resources and Services Administration, and were an HRSA senior advisor and a director of the Office of Quality and Data. As a senior advisor, you launched the Community Health Applied Research Network—which I’ve read is “the first patient-centered outcomes research program for underserved communities”1—a network that centered underresourced communities. You’ve also been chief medical officer within HRSA. You’ve consistently focused on minority health. You helped launch the National Health Plan Collaborative, aimed at reducing racial and ethnic disparities within large health plans, and you also contributed to the first National Healthcare Quality & Disparities reports.2 I am wondering, as you keep moving upstream, what have you learned about health justice through all of this work that you’ve led?

The way we engage with health right now is not about justice. That’s what I’ve learned.

KF: That’s an excellent question. What have I learned about health justice? I think what I have learned is that all of us have a part to play in it. You don’t think of the system as one focused primarily on health. Sometimes these systems do not support health. Health is very complex, and there’s what the system says it’s supposed to do and then there’s what the system is actually designed to do and what it delivers. The system is organized around sickness. Some describe it as a sick-care system. And it’s a transactional system that profits when people are sick. I tell people, “I didn’t learn about health in medical school.” I was saying this even while in medical school. I didn’t learn about how to take care of my own health. I had to learn how to take care of my health by going outside the medical establishment. So, I’m probably not typical, in that I was in the system and was distrustful of the system, right? That little girl who saw that kind of injustice knew what that system was about. I couldn’t articulate it, but I knew. I remember being in medical school, and I was very sick. My best friend (who is still my best friend) was saying that we needed to go to the doctor, and she kept on pressing me. And I wouldn’t. She said, “This is crazy, you are sick, let’s go!” I was rolled up in a little ball, and I blurted out to her, “I’m scared of doctors.” She was like, “What?” And I was shocked that that was what actually came out of my mouth. And so where I’m going with that is that the system does not work for most people, and I believe that every part of the system needs to be reimagined. The financing needs to be reimagined, the delivery of care needs to be reimagined, the way care is evaluated needs to be reimagined— every part of the system. The way we engage with health right now is not about justice. That’s what I’ve learned.

CS: In terms of having had to step outside of the system to learn about health, can you give an example of how you did that?

KF: One example is observing myself—observing my overall health, observing my weight—the space that I take up, observing even the stress in my life, right? Stepping out of the health system is learning practices like meditation. An important action of mine was moving toward Chinese medicine and acupuncture, looking into all these different traditions and modalities. So, I learned more about health by going into these different traditions—by taking a more active role in preserving my health through yoga or Qi Gong, for example; by being rigorous about the amount of sugar and flour in my diet. I felt comfortable going to these other traditions because when I was growing up, when we got sick at home, our first line of defense was what we called “bush tea.” My mother would make a tea for this, a tea for that, a tea for the other. And it was only when that first line of defense didn’t work that we would go to what we describe as “the healthcare system.” Moreover, I believed in my heart that God had given all the peoples of the world different healing knowledge

systems. Healing knowledge systems could not possibly be limited to the Europeans, from whom our medical system arose. And the system we have right now is neither about health nor is it about care.

CS: I have very—apparently—good access to healthcare. But I don’t use it often. I pay for my health insurance, which is pretty substantial, but I do a lot of alternative medicine, and I also do yoga every day. And when I go to the hospitals, I’m an anomaly for them. They’re not used to people being healthy and knowing how to be healthy—it’s not the norm for them. They don’t know why I’m coming for checkups, because I’m fine. I had a doctor tell me that I don’t have to come every year. The fact that I eat well and that I’m not overweight is just shocking to them. It shouldn’t be an anomaly, but it is.

KF: But it is. And they themselves are struggling with their health. I’ve not met many doctors who are themselves healthy. Doctors are suffering from all the things that people are struggling with in the wider society. That is a hard reality. Doctors who know about health have developed that knowledge outside of the medical establishment. They are some of our heroes.

CS: Right. I got into Ayurveda pretty early on, and it was very interesting to know that there is actually a science of health, and that’s Ayurveda. With colonization, it was driven underground, but it’s making a comeback. I’ve been a client of Dr. Joshi, who practices Panchakarma, which is a super intense six-to- eight-week cleansing/detox. I learned about this whole other world. And there’s a Chinese herbalist in Boston I go to, and I see a lot of people from communities of color there. It’s translatable.

KF: People understand it. They get it at a fundamental level. I recently learned from Dr. Carolyn Roberts, a professor of history at Yale University, and from historians of colonization, that when the Europeans went to West Africa in the seventeenth century, they came into contact with an advanced system of healing that drew off of plants and herbs.3 They drew on that “medical intelligence,” as Roberts described it, to maintain their health, and transmitted that knowledge, along with plant specimens, to British institutions such as the Royal Society of London and what today is the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. Historians and other social scientists are working to uncover what happened to that vast body of knowledge.

CS: You also talk about the power of leadership—and I know that when you went to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, your aim was to combine this work with leadership. Can you say more about how you think of leadership in this realm and what you did at Robert Wood Johnson around that?

KF: I’d been studying leadership for a long time when I joined RWJF. I was always very attracted to what was happening in the leadership space, and I was reading journals like the Harvard Business Review, and I was just really taken with the innovation that that journal was reporting on—people were actually thinking of solving problems. Now, mind you, what was behind that was how much money they were going to make—I recognized that; but I also recognized its significance, and that people were tackling big problems. And it just didn’t seem that people wanted to do that in medicine. There was just the status quo, and people were unhealthy, people were sick and dying, but that was okay. Even in research, so many people were asking very small questions while the big questions were ignored. It was the early aughts. I felt that I didn’t belong in that space. So, I very quickly abandoned that space and began my own practice of leadership, trying to be the change that I wanted to see. I read lots of books. Books like Nice Girls Don’t Get the Corner Office, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, The Effective Executive, for example.4 But I wanted more—not for myself, but for us poor people. Black and Brown people. People of color. And I was impatient. I wanted change and I wanted it now. I think sometimes people didn’t understand that. People I worked with kind of undersaw what I was doing—there was a perception that it was about my own personal ambition, about trying to get ahead. It wasn’t.

CS: It seems like you’re saying that even in these different organizations where you were working, there wasn’t the understanding of leadership. That wasn’t a thing.

KF: It wasn’t a thing. And when I was at the university, for example, there were people advising me to take a big data set, write lots of papers, and get promoted. But that was not what I was about. That’s never been what I’m about. And so initially, in many ways I failed as a scholar. And I failed as a leader. My first attempt at leadership was a failure. Why? Burnout. Unhappiness at work. I was hyperfocused on my goals and not really connecting with the people I was working with—because I had not as yet internalized that the means and ends needed to align. I had not yet learned how to embody the change that I wanted to see. There was a disconnect between what I wanted and how I was showing up every day with the people around me. I went through some jobs pretty quickly. There was just dissatisfaction. There was not a lot of joy or health for me in these roles. And I think a turning point for me came around when I turned forty. It just became so clear that what I was building and doing wasn’t working. It was fragile. And my marriage collapsed.

CS: Where were you at the time in terms of your job?

I consciously bring spiritual resources to my endeavor. This is not just about me, right? I live in a world where there are other actors—like you and me—who are aligned; but there are also actors in the spirit world, who support me and us. And I call on those actors.KF: I was director of the Office of Quality and Data at HRSA’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. But it was just clear that my life was not working. And I had a spiritual awakening.

CS: So, that was the next question. You call yourself a spiritual activist, and I’m wondering if you can share what you mean by that and how that informs your work.

KF: Last time we met, you said that your vision is so big that you’re not overly bothered by what’s happening here. I loved that. I consciously bring spiritual resources to my endeavor. This is not just about me, right? I live in a world where there are other actors—like you and me—who are aligned; but there are also actors in the spirit world, who support me and us. And I call on those actors. I call on those ancestors. I invite them in, I talk to them, I seek their guidance. And I do this consciously. It’s something—an aspect of African worldview—that is totally aligned with my faith tradition, which is that this world here is just a world, not the world. There are many worlds of God, and this is just one of them. So, when I understood that my time is endless, I stopped stressing over small shit, you know what I mean? Of course, I get treated like everybody else, I go through tough times like everybody else—but I don’t overly stress. I never lose hope. Because I have time. There is time.

CS: What do you mean by that?

KF: If I don’t learn what I need to learn here, there are other worlds. And the only thing I leave with is my consciousness. When I die, everything but my consciousness stays here. If I don’t get it here, I’ll get it elsewhere.

CS: How does that affect your leadership? How you approach leadership now? You said you had crashed a little bit and then you had this awakening. . . .

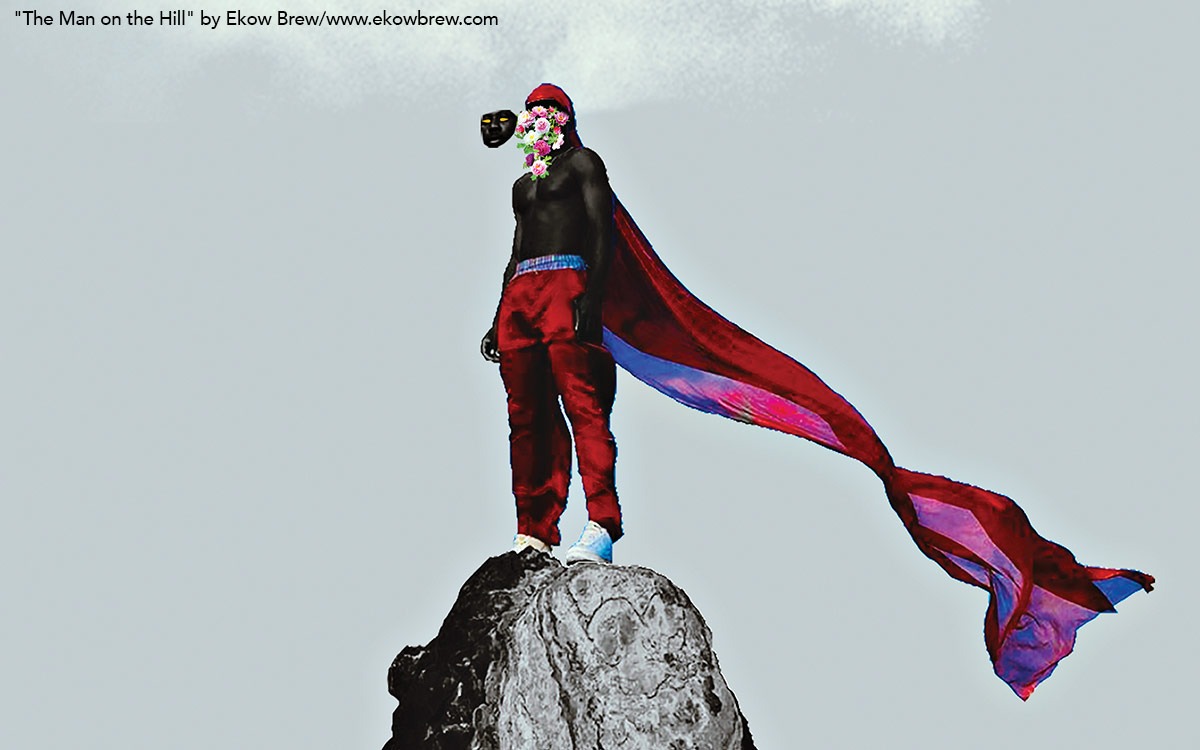

KF: I approach leadership now from a very different place. For example, it’s no longer lonely. It’s not competitive. People say it’s lonely at the top—well, I’m not at the top of anything, you know? It’s subtle—I mean, yes, I’m in a hierarchy at RWJF, but I don’t engage it like I’m below anybody or above anybody. And I don’t expect people to approach me like that, either. And that feels so radical to people. I don’t expect people to bow down before me; I don’t expect them to cater to me. And I don’t expect to bow down or cater to others, either. I put my cards on the table, and I invite others to put theirs on the table so that we can figure things out together. I see my role as leader as holding the vision, holding what it is we’re trying to do here and how we’re going to do it together. Leadership is a process that I engage in, and not necessarily who I am.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

CS: Is that when you moved to Robert Wood Johnson? Or just shifted more toward philanthropy and supporting leadership?

KF: It was a process. If you look at my CV, you can see I was chief medical officer for a year. And I was just losing my mind. The job was not working for me; it was killing me. It wasn’t working for the organization either. Fortunately, at the request of my boss, I moved to another part of the organization. And for about a year or two, my workload decreased dramatically. I read. I took a memoir-writing course. I was able to reimagine my life. It was the best. It was a much-need respite, because for years I often worked in the office from seven a.m. to six p.m. I was often late picking up my daughter from aftercare. I was one of those mothers who had to pay late fees in aftercare or get caught speeding while rushing to pick up their child. It also helped me to connect more deeply with my daughter.

CS: That’s amazing. What was the pivot?

KF: The pivot for me was around a different understanding of leadership. My mission became not being the person who needed to be on top so as to be able direct people to take action. You know, there’s this idea that you have to get to a certain place for you to be able to take on that role, and everybody is always looking for who is the highest ranking person. I, too, had internalized that kind of striving—wanting to get to a place before I could be the change that I wanted. That is a joke, Cyndi. All of us have a role to play in this change, and we start now, wherever we are. So, I went to coaching school. Guided by my faith, I spent four or five years getting trained in ontological and generative leadership. I’m not talking about book learning only; I’m talking about understanding what it means to be fully human, unlearning the many unhealthy habits (competitiveness, thinking small, insecurity, disconnection from my body) that I had picked up over the years in school, in my family, and in wider society. And I began to see myself as somebody who serves. I remember the first time that I really understood that in my body. So, I had this pet peeve. Whenever I had to fill the paper cartridge before using the office copier, I would be rageful and resentful, thinking not only that I was doing someone else’s job but that it was beneath me to do so. My time was too important. I remember one moment when I started with the rage and resentment drama and something inside of me softened. It shifted. I just let go of those two destructive emotions. I understood then that refilling the paper cartridge was no less important than being invited into a meeting with the highest-level person in the organization. It was all service to the mission. That was a powerful experience for me. I felt free, no longer bullied by rank and position. That’s a big deal for someone who grew up in a colony. I began to pick up trash on the street, because I understood it was service. Service to others would become the criterion that I use to evaluate my actions. Who benefits? How am I contributing? became the defining questions of my life. I dedicated myself to supporting leaders in whatever context I met them.

Nowhere in my schooling did I learn about the importance of my emotional life and how to regulate it. But our moods and attitudes matter tremendously, because they determine whether we connect with each other, how we listen or don’t listen to each other, and whether we will share the space or try to dominate.

CS: And how did you do a four-year course on generative leadership? Is that an established thing or did you design it for yourself?

KF: These are established schools of personal and organizational development. First, I did a Newfield Network’s ontological learning training program, which is about understanding on a practical level what is a human being. Then, I trained at the Institute for Generative Leadership, and there I learned a lot of distinctions that helped me to understand myself and learn how to work more powerfully with others in complex arrangements, such as organizations. For example, I learned that how I show up is more important than how much I know. That is a big one, because I got a lot of schooling, and schooling is all about what or how much you know. Nowhere in my schooling did I learn about the importance of my emotional life and how to regulate it. But our moods and attitudes matter tremendously, because they determine whether we connect with each other, how we listen or don’t listen to each other, and whether we will share the space or try to dominate or even annihilate each other. I learned how to listen to other people’s seemingly contradictory perspectives, hold them even when that created tension in my mind and body, and avoid othering people. I learned to speak my opinion not as demand but as an invitation for us to have a fuller picture of reality. I learned that I can always have “do-over” conversations. I applied these skills to my work at the foundation.

CS: What did you do at RWJF?

KF: I worked with a team of people who developed and managed a portfolio of programs that invested in people who were committed to advancing health equity. Every year, we invested more than $60 million in leadership programs. It was important work, but we learned quickly that there was a gap between the biggest challenges, such as structural racism or other structural inequities that these leaders wanted addressed, and the experience they were having. So, part of my and my team’s role at the foundation was first to help the foundation understand that gap and then to begin to reimagine what kinds of investment could begin to bridge it.

CS: What did you figure out while you were there? By the way, I think it’s amazing that a foundation is supporting leadership so specifically and in such a big way. It just seems like a big commitment, which I don’t see a lot in philanthropy.

KF: Yes! RWJF has a long-standing commitment to supporting people making change. It’s a huge commitment. They supported me from 1997 to 1999, while I was doing a research fellowship at Johns Hopkins. They invested in me. I was grateful for the support that they gave me. But I never thought I would work with them, based on what I knew of the organization at that time. They were very much interested in insurance and coverage, and while I think that’s important, it’s just not my jam. It’s not the thing that I was interested in. So, when they committed to a culture of health, and committed to leadership programs to address health equity, that’s when I raised my hand and said, “Hey, I can help you.” And they invited me into the organization.

CS: What did they mean by “culture of health”? Was it about promoting health, as in moving beyond insurance?

KF: Moving beyond insurance to what is called the “social determinants of health.” Understanding that there are barriers that are built into society that keep people from being healthy. And I think there’s so much injustice at the source. Injustice generates not just bad health and poor health but also unhappiness and mental distress. Health isn’t just what we are taught to think of as purely and directly physical. And even when people have diseases or medical conditions, social factors are often at the root of these problems. They play an oversized role in contributing to disease in that they are often ignored by the establishment. Those social forces place and maintain some people in toxic environments. The quality of the air that people breathe, the amount of green space they have access to, the toxins that they drink in the water that flows through the kitchen sink, how far they have to travel to their jobs, how safe or dangerous their jobs are, whether their children have access to environments that stimulate their learning, the number of jobs that they have to patch together to barely pay their rent. These conditions don’t occur randomly. These conditions are designed to be that way with specific segments of the population in mind. And all these social factors exert a cumulative toll on human health. They undermine it. I love that RWJF is committed to that understanding of—and to addressing—health injustice. That’s why I joined them.

CS: As we get to this high level ontologically in terms of how we are with each other, how do we address this?

KF: I think health is one part of a prism. The environment is another part. And I think how we address it is exactly where we are and what we are grappling with right now. Some people are working in organizations to disrupt these patterns of injustice, but other people are also reimagining what health could look like. I mean, why is it that Ayurveda—an approach to medicine that aims to restore the body back to health or balance, not just chase symptoms—is only available to a small, select set of people with resources? Why do you have to pay for it out of pocket?

CS: I remember wanting to find an Ayurvedic doctor in Boston and finally finding a clinic in Wellesley, which is a totally white, very wealthy, elite. I drove all the way out there, and they only had one Ayurvedic practitioner—and after a few minutes, she said to me, “I don’t think I can help you; I think you know more than me.” And I just thought, How can that be so? I literally laughed with her at her not being able to help me. And then through my meditation community I met a woman who was an Ayurvedic practitioner. She had cancer and had gone to India and done Panchakarma repeatedly, and her cancer had disappeared. So, she became an Ayurvedic practitioner.

KF: What is Panchakarma?

CS: Ayurveda is very noninvasive. It’s all about how you live, how you eat, how you balance your life—all the things and ways of living that promote health. Panchakarma is the most intensive part of the practice, and it was very subordinated during colonialism. People could practice it, if they knew it, informally, but there weren’t many practitioners, because it is the most advanced part of the field. So, Panchakarma started to disappear. It has started to come back in the last few decades, I believe. Some of the families that had it in their past before colonialism decided to bring it back, and the Joshis—I mentioned Dr. Joshi earlier—are one of those families. But there are very few practitioners doing it.

Basically, you travel to this retreat space, where you stay for between six to eight weeks, depending on your level of illness, and are treated with massages, oils, purges. They move all the toxins from your extremities into your body and your system, and then you expel it. You expel it through all your orifices. So, you’re expelling toxins for six to eight weeks. And the woman from my meditation community said that it’s very, very hard. You’re alone, but you have five to ten people taking care of you, because it’s very emotional. She said once all the toxins get into your system and are ready to be expelled—it takes about a week or two to move it into your system—you expel for weeks. And she said that when she was vomiting—when she got to the part of it coming through her digestive system—she was pulling out cords of tangled mucus and toxins. And while she was pulling it out, she felt like she was almost dying. Because all these emotions were caught up with it. It’s not just physical, right? It’s almost like a ritual— very intense. People have to be there to help you, because it’s very hard to go through that. And then they give you massage. And the food that they give you is super pure.

KF: And you had that done?

CS: I’ve never had it done. It costs a few thousand dollars to do it. I was never sick enough to do that. A friend of mine went and did it in India. And there is one place here, in Arizona, I believe, that does a very light, surface-y Panchakarma—they don’t even call it Panchakarma—over two weeks or something like that. But if you want a real one, you have to travel to India and be able to live there for six to eight weeks. So, it takes money. People don’t usually do it unless they’re really sick. Joshi does that in India and then he travels around the world. You can schedule meetings with him when he’s in your location. I first met him and his wife, who is a reproductive doctor, after I had been diagnosed with migraines and the headaches had been getting worse and worse. And I had had a few miscarriages. I didn’t realize they were connected. The first time I went to see him, I had such a headache. And he started to tell me all these things like, “You can’t eat bread.” I was just like, “You don’t understand. I’m dying. You’re telling me to stop eating bread?” And he said, “No, no.” I didn’t understand that it was all related. His wife explained to me that in Ayurveda there are seven levels of health. And so when your body is not at optimal health, the first thing to drop is your reproductive health, because you don’t need it. Ayurveda is organized around doshas, or bodily energies, and works on whole body balance and health.

KF: I’m learning about doshas now. I’m in a yearlong program studying and practicing the daily habits of Ayurveda.

CS: So, you’ve had this amazing trajectory with these shifting levels of consciousness as you keep moving into understanding how to even be in this work. What’s next for you?

KF: My time at RWJF came to a close at the end of September, and I’ll be joining the faculty at Johns Hopkins [Bloomberg] School of Public Health, where I’m being funded to study and write on medical racism over the next three years. I’m really excited, because I’m coming back to medicine. I’m coming back to medicine to engage it from a place of really deep care and love for what medicine can be. And I think racism is part of what prevents medicine from being a more powerful force for healing. I believe medicine can be healing, but it’s not as healing as it could be right now. Where I’m coming from here regarding racism and the experience that Black people have, is that it turns out that Western medicine and racism coevolved—so, you can imagine how toxic that is.

CS: I remember when I was at Boston College and I took a class with Mary Daly, and we read her book Gyn/Ecology, on how the gynecology field was developed from the Holocaust and experiments that were done on women.

KF: That’s right. On enslaved women. J. Marion Sims, and all the big figures—Benjamin Rush and Samuel Cartwright—who built their powerful careers on biological racism, arguing that Black people were biologically different, aka inferior.5 So, what does that do to a field? I want to write for a general audience on medical racism, so as to make the historical and the contemporary aspects of it more visible to everyday people. I’d like it to be narrative nonfiction, not a technical book. A book that women will read in book clubs, for example. I never imagined I’d be writing a book; I have the opportunity now to step into the unknown and bring my vision to light.

NOTES

- “Helping Organizations To Manage Growth—Without Added Cost,” S. 1 Princeton Info, October 10, 2017 (updated January 11, 2022), www.communitynews.org/princetoninfo/business/survivalguide/helping-organizations-to-manage- growth-without-added-cost/article_d20dbad1-e349-5f46-bcb9-12739bb5a33b.html.

- The National Healthcare Quality & Disparities report, now in its twentieth year, is published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and The Research and Quality Act of 1999 mandates that these annual reports go to Congress. See www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578556/.

- Carolyn Roberts, “West African medical knowledge, the slave trade and the Royal Society,” The Royal Society blog, October 26, 2021, royalsociety.org/blog/2021/10/west-african-medical-knowledge/.

- Lois Frankel, Nice Girls Don’t Get the Corner Office: 101 Unconscious Mistakes Women Make That Sabotage Their Careers (New York: Warner Business Books, 2004); Stephen Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change, rev. ed. (New York: Free Press, 2004); and Peter F. Drucker, The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done (Harper Business, 2006).

- Sarah Zhang, “The Surgeon Who Experimented on Slaves,” The Atlantic, April 18, 2018, theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/04/j-marion-sims/558248/. For more on Samuel A. Cartwright and Benjamin Rush, see Judith Warner, “Psychiatry Confronts Its Racist Past, and Tries to Make Amends,” New York Times, April 30, 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/04/30/health/psychiatry-racism-black-americans.html.