September 8, 2020; GreenBiz

Since COVID-19 hit the Unites States earlier this year, home gardening has been rising in popularity—so much so that seed companies saw their highest sales in over 100 years. And this revival couldn’t come at a better time: the pandemic presents a perfect opportunity to reduce world hunger by putting food production back in the hands of local communities and ending food waste with a circular food system.

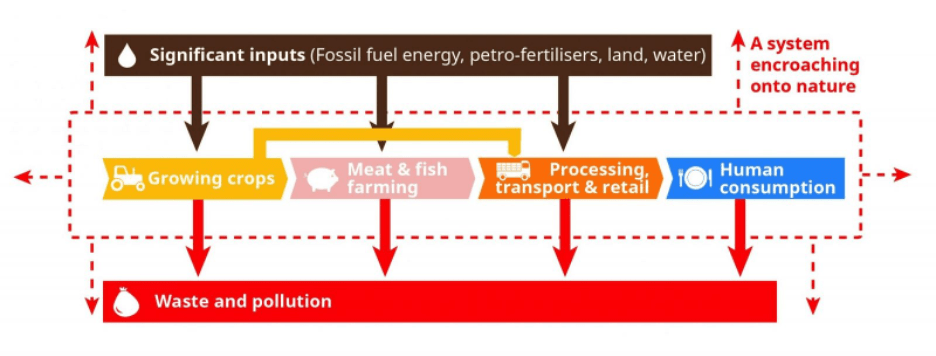

The reality is that hunger in the US is not a result of food scarcity. In fact, nearly one third of all food produced each year goes to waste. The US saw this on an extreme scale when the pandemic began and farmers were forced to throw their products away as demand from restaurants and schools dried up. As the below chart makes clear, waste is generated at every stage of production:

As you can see from the image above from Feedback, a nonprofit that works on exposing systemic food problems, each step of food production generates waste and other environmental detriments: chemical waste and greenhouse gas emissions as food is produced in large-scale agricultural sites; more emissions as food is processed and shipped across the globe; packaging waste as processed food is consumed and discarded, to say nothing of the aforementioned food that gets thrown away without ever making its way to a human mouth.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

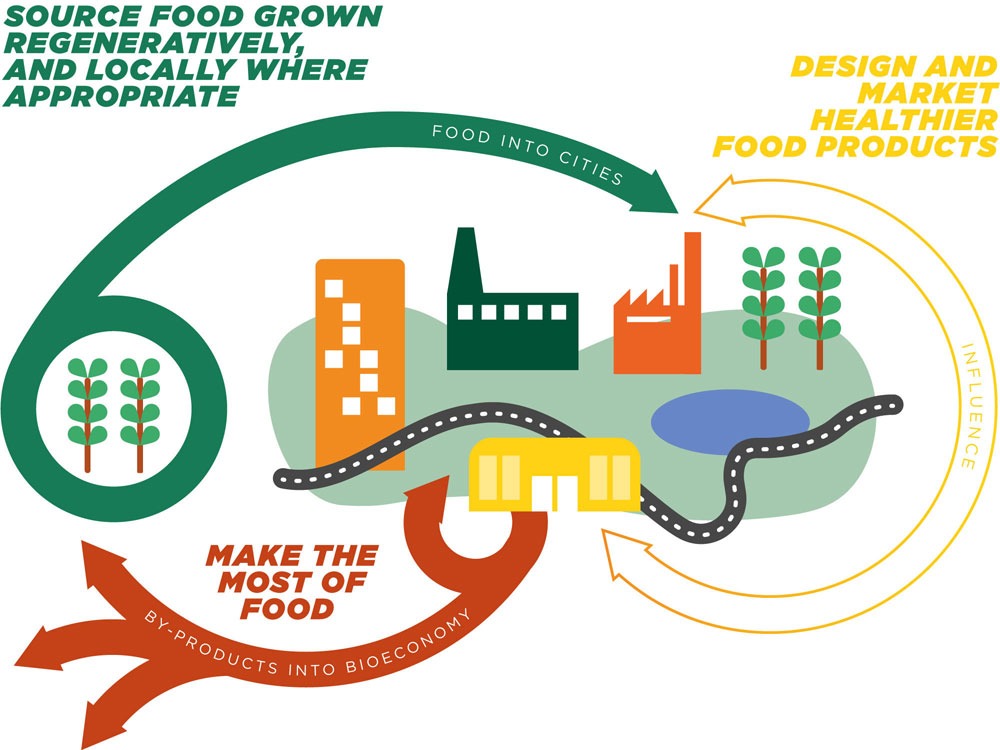

Fortunately, there is a less wasteful way. A circular food system in which communities take food production into their own hands would not only eliminate many of the environmental hazards of our current food system, it would also ensure that communities are self-reliant and less likely to suffer food shortages when major events such as the current global pandemic throw a wrench in food supply chains.

So how can we create a circular food system? Simply put, the loop needs to be closed at every step of the way. Shifting the goal from generating revenue to feeding communities would eliminate waste and environmentally harmful practices, while giving power back to growers and recreating the relationship between communities and their food. According to multiple sources, like Feedback, GreenBiz, and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, efforts should include:

- Localize food production. Right now, most cities rely on far-flung farms to get their food, which means food has to be trucked or even flown in to make its way to consumers. Localizing food production, especially around urban areas, would not only cut down on carbon emissions from transporting food, it would also allow for easier communication between farmers and their clients. By keeping food production close to home, farmers could work directly with the people they’re feeding to make sure food is distributed and not wasted. Smaller-scale operations like community supported agriculture shares and community gardens also support a localized food system—and are more likely to already be utilizing organic methods.

- Focus on closed-loop growing methods. Over time, agriculture has changed drastically from a vast constellation of small, family-owned farms to a concentrated network of large commodity-crop farms. Under this model, farms are less likely to grow a variety of crops for local distribution, opting instead for cash crops like corn and soybeans that can be exported all over the world. Not only are these crops less likely to feed communities, the means of high-intensity production can also be incredibly harmful. Most mega-farms rely on GMO [genetically modified organisms] crops and chemical fertilizers and pesticides, all of which have been linked to widespread degradation of the soil and pollinators that are vital to farming. Alternatively, a closed-loop farming system would employ methods aimed not just at producing the most crops this year, but also guaranteeing soil health and biodiversity for generations to come. Farmers can use low-cost practices—like composting leftover organic matter into fertilizer—that also reduce waste and promote overall health of the farm ecosystem.

- Create conscious consumers. There’s no denying that one of the greatest sources of waste in our food system is the result of our reliance on processed foods. These foods take a lot of resources to create (imagine the energy output to convert corn into corn syrup!), generate a lot of cardboard and plastic packaging waste, and tend to be the least healthy option on any grocery store shelf. And what’s more, the dates we print on that packaging often encourage us to throw out food that’s still perfectly good to eat. By creating a healthier food system that incentivizes consumers to eat whole foods straight from the source, and to keep food around until it’s truly ready to be thrown out, we can cut down on waste at the consumer level. The cherry on top would be adding compost to local waste management services, so that each household could contribute to the creation of organic fertilizer that local growers need.

Shifting to a circular food system won’t happen overnight, but the pandemic could encourage shifts in that direction. The effects of COVID-19 on the US economy have led to an additional 17 million households experiencing food insecurity. We can no longer wait to create a food system that prioritizes putting food in the hands of the hungry. Closing the gaps in our wasteful, profit-driven food system will require all hands-on deck: farmers, communities, government entities, and nonprofits. As Arundhati Roy stated in her essay, “The pandemic is a portal”:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

If we choose to work together and walk through the portal, we might even be able to shut the door on world hunger for good.—Tessa Crisman