Editors’ note: This article was first published in summer 2007 and is featured in NPQ‘s special winter 2012 edition: “Emerging Forms of Nonprofit Governance.”

When it comes to governance, boards of directors tread a very fine line. Those who seek to lead the organization run the risk of usurping the role of the CEO. Those who follow the CEO’s lead run the risk of abdicating their responsibility and joining the ranks of management. In fact, the true value of governance lies neither in leadership nor in followership, but in the unique role of “loyal opposition.”

For many years, boards of directors of Canadian corporations and public institutions were criticized as being “parsley on the fish” (decorative but not useful) or an old boys’ club, where protection of fellow members and mutual back-scratching ranked ahead of any other obligation. Largely ignored by organizational theorists until ten or fifteen years ago, boards are now intuitively understood to be important, but their function is still not fully conceptualized. This lack of clarity is problematic for individual directors striving to exercise due diligence and fiduciary responsibility and for regulators and quasi-regulators seeking to establish guidance on good practice.

Certainly, it is no longer appropriate (if it ever was) to rubber-stamp every senior management proposal. But, boards that seek to exert more control and influence over the executive team may only escalate political maneuvering. As a result, power either remains with the executive team or shifts into the hands of the board—or there is like-thinking among the two groups. While organizational politics are a reality, power struggles of this type are detrimental to the board’s ability to exercise its mandate most effectively.

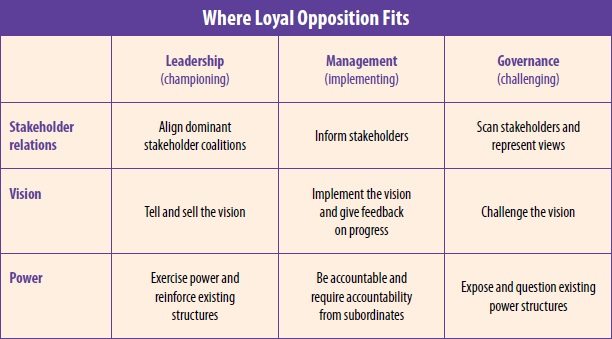

Rather than look at the role of the board of directors, it’s helpful to focus on the functions of governance, leadership, and management. If an organization is to operate effectively, each of these three functions must be performed by someone or some group.

Organizational theory recognizes that the leadership function is about creating a transformational vision of the direction in which the organization should be heading and “telling the story” in a compelling fashion. Power comes to leaders who create a cohesive, inspiring story that all will follow and believe, and strategic direction falls out of that vision. The more compelling the story, the less the vision is questioned and the stronger the leader. John Roth’s ability to create a story about Nortel that so few questioned or doubted is an example of both the power of charismatic leadership and the risks of being believed too much.

The management function is to implement the vision and bring the strategy into operation. Together, leaders and managers must ensure that stakeholders, both inside and outside the organization, see the strength and wisdom of the direction established and that the confidence of shareholders is never shaken.

So what is the function of governance within this framework? Directors know that they should not meddle in management, but they might not understand that governance is distinct from leadership. Many directors are also strong leaders in their own right and may see little alternative to the board fulfilling or supporting the leadership function. Well-intentioned, sincere, and committed, they slide into the leadership function by creating the vision themselves or by guiding the CEO, especially if the CEO is seen as weak.

| The concept of loyal opposition means being opposed to the actions of the government or ruling party of the day without being opposed to the constitution of the political system. In Japan, the United Kingdom, and many other Commonwealth countries, the leader of the party possessing the largest number of seats in Parliament while not forming part of the government is termed the loyal opposition. Their constitutional function is to scrutinize government legislation and actions. While frequently opposing the ruling party policies at every turn, the leader of the opposition is not opposed to the government’s right to rule. |

The function of governance is to protect the organization from a too-successful leadership role. The compelling vision created by a charismatic leader can become a type of prison—a tunnel vision. Leaders become the hero or heroine in the drama of their own creation. As both the producer and the star, they cannot step back from the script that continually unfolds to see if the story line is still coherent. In a world of uncertainty, rapid change, and environmental chaos, plots can quickly become outdated, but the writer may not notice. Business schools teach case studies of companies that misread changes in their environment, in technology, in the demographic profile of customers, or in society’s values. Aspiring managers are taught to monitor and scan their environment and also to be self-critical and aware.

The challenge, of course, is that a truly visionary and compelling leader has to believe his own vision. Ambivalence is quickly detected, and leaders who express doubt are accused of not walking the talk or of not being strong and dynamic. If you are seen as a winner and a leader of distinction, it is almost impossible not to be caught up in your own myth. We can say, “Reflect, be humble, share your weaknesses and be self-conscious,” but this is asking leaders to be heroic beyond what is reasonable or even realistic. One person simply cannot do it all.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Instead, every strong leader needs a sounding board, an outside mirror that will help in monitoring the increasingly unpredictable environment. Reflection and questioning, reframing and reassessing are key responsibilities of the governance function. Therefore, a board’s performance of that function can challenge the leader’s vision, ask whether it is in alignment with the environment, assess the risks implicit in it, and obtain assurances that management is implementing it effectively. A board can also confront the leader with different interpretations of the script. The story line will grow stronger and more compelling as the leader defends the vision and adjusts it based on the meta-level critique of the board of directors.

Governance should be a “radical” function that seeks to challenge the root assumptions of leadership, to address those matters that are normally taken for granted or are not discussed. Governance involves deconstruction of the deep structures of power (the glass ceilings, the unspoken privileges, the inequities that are so familiar as to be invisible). It involves generating alternative visions or scenarios and testing to see if they are more robust and resilient than is the current vision. It also involves asking what-if questions and celebrating diversity and multiplicity of views.

A robust governance function is a challenge to the vision from which the leader derives power, and some leaders may find this personally threatening. Loyal opposition is not always voiced in friendly tones, but the clash of opposing ideas can be as productive as sotto voce suggestions. Far greater than the risk of offended sensibilities is the risk to the organization when no governance function is being performed. Governance is absent if the board sets the direction and fulfills the functions of leadership itself, or if the board and executive share the leadership, or if the board merely rubber-stamps the executive’s vision. No governance is being performed if the board unquestioningly believes the vision and sees it as an objective reality. The outcome is an organization that risks being limited by an outdated view of the world, under a leadership blind to certain events taking place around it.

Top management is not the only place where leadership functions can be performed; middle and lower management are not the only place for performance of management functions, and the board of directors is not the only place for governance. Each function can be performed at many levels. Employees, for example, can deliver invaluable critiques of the existing vision (if the leader is humble enough to listen), based on their day-to-day, front-line experience in working with customers, suppliers, competitors, and other critical stakeholders. As well, different organizations at varying stages of development may assign functions differently. For example, a volunteer-driven nonprofit agency may have members of its board of directors play a key role in shaping the organization’s vision. There is nothing wrong with that, as long as the board recognizes that it (or someone) must also step back into the governance challenge role.

However, board members should examine the governance function of their organization and assess whether it is being performed adequately. In these increasingly uncertain times, both strong leadership and engaged, effective governance are required, as is diligent management. Leadership, management, and governance must be brought to bear on the key aspects of work throughout any organization.

Reproduced with permission from CAmagazine, published by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, Toronto.

Patricia Bradshaw, PhD, is dean of the Sobey School of Business at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Peter Jackson, CACA, is an independent consultant in Toronto. He is also CAmagazine’s technical editor for control.