Can movement nonprofits create and sustain liberatory and resilient structures, cultures, and practices—and still be effective and efficient in their operations?

Nonprofits remain, at best, imperfect spaces to engage in democratic movement work. There is still much to learn, uncover, disrupt, and transform.

This question was at the center of an experiment led by the Nonprofit Democracy Network, a fiscally sponsored project of the Sustainable Economies Law Center. The experiment, called Collaborate to Co-Liberate, brought together over 200 practitioners from nearly 90 organizations across the country (and beyond) for 15 months to co-develop ways to build accountable, self-governing, and radically democratic organizations that embody liberatory visions while preserving overall effectiveness.

Participatory self-governance is not easy work. While progress has been made in developing worker self-directed nonprofits that empower workers while advancing program work, and a growing infrastructure exists for nonprofits that seek to democratize internal decision-making, nonprofits remain, at best, imperfect spaces to engage in democratic movement work. There is still much to learn, uncover, disrupt, and transform.

Democracy is also difficult. Central to the cohort’s work was learning to recognize that some contradictions are inherently irreconcilable within workplace or organizational boundaries—and thus need to be explored with curiosity and non-attachment.

The Quick and Dirty on the Nonprofit Industrial Complex

The worker self-directed nonprofit form (along with other activist nonprofit structures) was envisioned to remedy the various harms of the nonprofit industrial complex.1 The INCITE! network of radical feminists of color popularized this term in 2004. Far earlier, organizers and activists were identifying and naming the patterns and dysfunctions of “movement capture” and innovating creative ways to resist it. In 1963, Civil Rights activist Ella Baker said she was “very much afraid of this ‘Foundation Complex.’ We’re getting praise from places that worry me.”2

As Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us in The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, “Foundations are repositories of twice-stolen wealth—(a) profit sheltered from (b) taxes” (46). If it weren’t for charitable deductions allowed by tax laws that enable wealthy individuals to shield their wealth from the federal estate tax, billions of dollars of this wealth would have become public funds, accessible to the governing electorate through mechanisms, however ineffective, of public accountability. Instead, foundations whose boards and trustees substantially skew wealthy, White, straight, cisgender, and male oversee decisions about what causes are worthy of receiving their money. Revenue-dependent nonprofits often cater to these priorities rather than to their constituents or movement origins.3

These conditions lead to many of the counterrevolutionary elements of the nonprofit world we see today: stratified, undemocratic workplaces in which power is concentrated in the board and/or executive team; underpaid and overworked program staff who run through cycles of burnout; programs being developed by people without relevant lived experience and often centered on saviorism rather than solidarity; punitive conflict resolution processes that mimic corporate structures; and so much more. In a growing number of nonprofits, albeit still a small minority of them, staff and boards are seeking to address these trends by moving toward some form of worker self-directed governance structure.

Prefigurative Politics and Shared Power

For as long as these destructive patterns have arisen in movement formations (whether formally incorporated as a nonprofit or not), activists have organized to transform them. Many are inspired by the idea of prefigurative politics—the notion that by creating in the present the future world we wish to see, it makes it possible not only to advocate for a better world but to demonstrate, through action, that a better world is possible.

Historical examples abound—from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy on Turtle Island (North America) to the Diggers in 17th-century Britain, to the Paris Commune in the 19th century, to early 20th-century movements such as the Industrial Workers of the World and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica in Spain. In more contemporary movements, we see these values embodied by groups including Ella Baker and the Young Negroes Cooperative League, the First Rainbow Coalition (Chicago Black Panthers Party) to the Combahee River Collective. In South Korea, the 1980 Gwangju Uprising that led to the end of dictatorial rule is yet another example.

Today, we see this spirit in the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST) in Brazil, the Zapatistas in Mexico, the Occupy movement and its ongoing influence as reflected in the municipal government in Barcelona, Spain (Barcelona en Comú), the rise of Healing Justice lineages, and many others. So many have aspired to build the more beautiful, liberatory world we know is possible by engaging in the deep, hard work of sharing leadership, dismantling systems of power and oppression, and living into our values in the here and now.

Building Liberatory Structures

At the Nonprofit Democracy Network (NPDN), our goal is to build a community of practice that “makes the path by walking”—a reference to a poem by the famed early-20th-century Spanish poet Antonio Machado. We take inspiration from Mariame Kaba, who says about abolition (of the Prison Industrial Complex), “We’ll figure it out by working to get there.”4

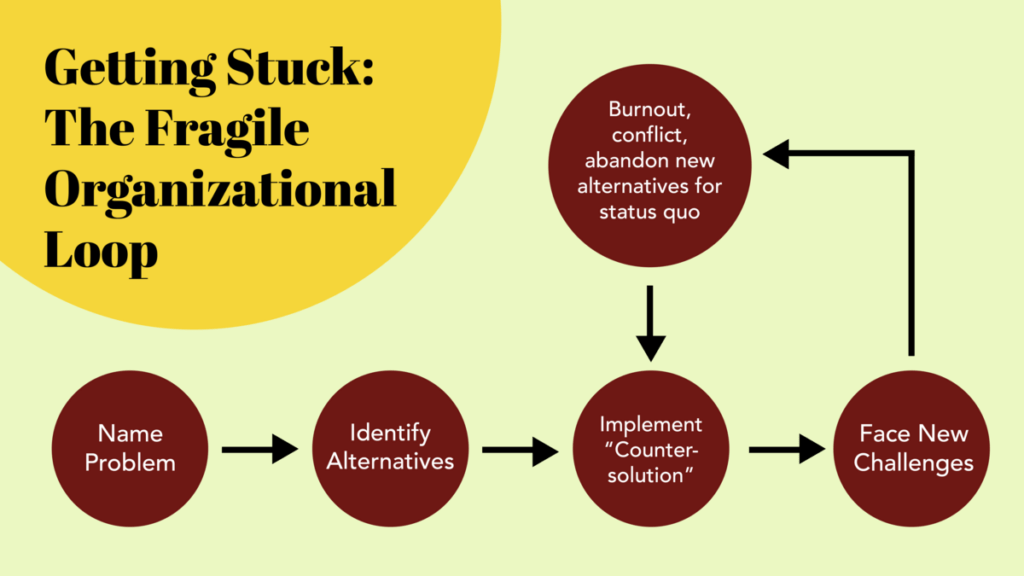

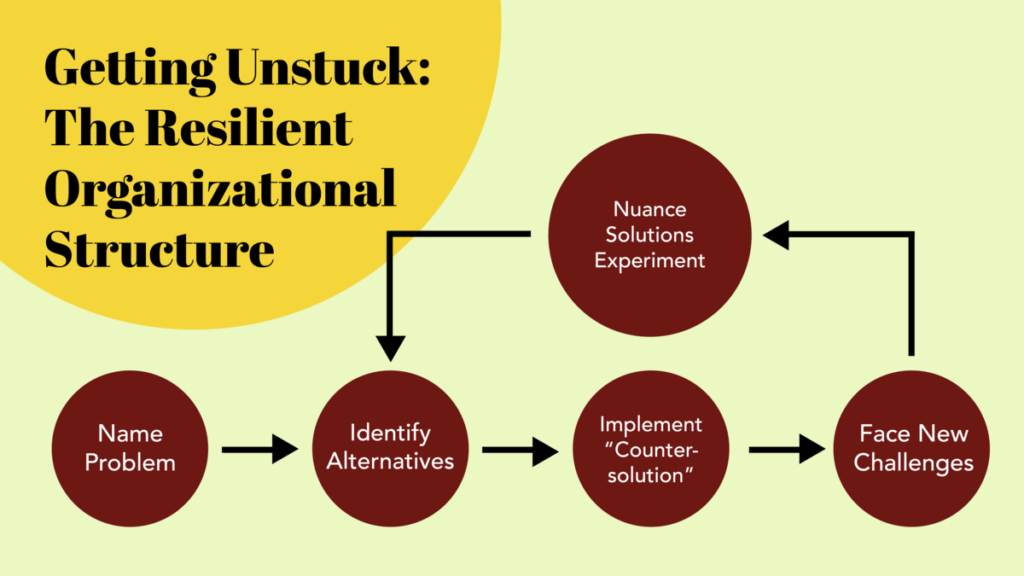

While experimentation is key, we have found there to be a cycle of organizational growth and change, a cycle that can induce either organizational resilience or fragility. If nonprofits that aspire to be movement organizations can understand and anticipate these cycles, the chance of advancing sustainable, liberatory practice is enhanced.

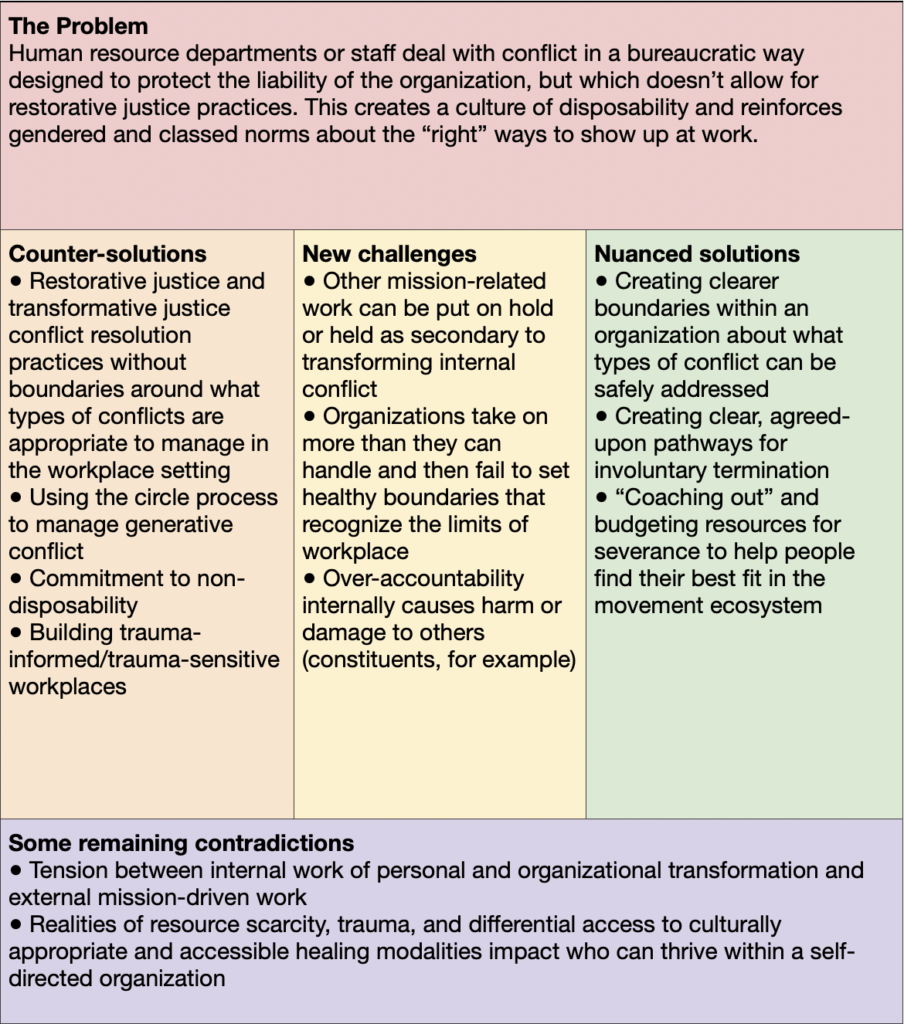

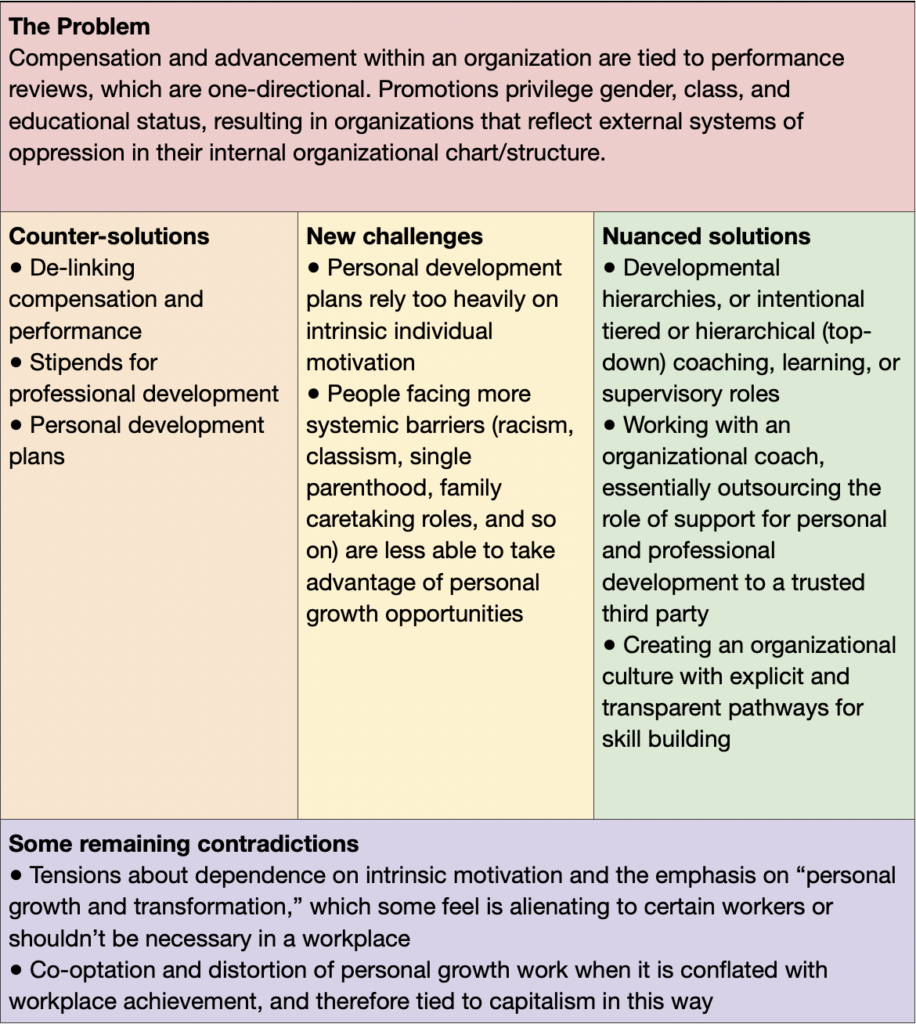

Organizations often seek to implement…counter-solutions: somewhat oversimplified solutions that are the obvious opposite to the issue at hand.So, what does this process look like? The first step is identification—that is, identifying a problem impeding liberatory practice. By naming what is wrong, it becomes possible to begin a journey through organizational change.

Once a problem is identified, the first necessary phase of change involves developing new alternatives. Many organizations who first connect with the Nonprofit Democracy Network express immense excitement at the mere possibility that things can be different within their organizations: power can be shared rather than hoarded, a culture of care and reciprocity can replace one of exploitation and overwork, conflict can be generative and restorative rather than divisive and toxic. Often, this excitement translates into an idealistic view that new structures are possible and will fix old problems. Call this the idealistic phase.

From this idealism, organizations often seek to implement what I will call counter-solutions: somewhat oversimplified solutions that are the obvious opposite of the issue at hand. For example, organizations struggling with nondemocratic, hierarchical decision-making that often excludes the most marginalized within the organization may opt toward an entirely flat, collectivized structure where decisions are made by consensus, with all people participating equally and fully.

Depending on the organizational context, this phase of implementation can be easy and exciting or exhausting and painful (or something in between). It often includes the hard work of bringing existing powerholders and decision-makers on board to the change and, in so doing, addressing and accounting for many of their fears, a process that may result in compromise.

After working out the kinks of the structural change, however, organizations often enter the second stage of change, in which things get complex and nuanced. Here, I believe, is where the real potential lies. Often, in this phase, people begin to recognize that the “counter-solution” they implemented addresses many issues, but it doesn’t solve all the problems; and in many cases, it creates new problems.

To extend the example of decision-making above, in a now collectively run consensus-based organization people may find that members with more “rank” often wield more power, unintentionally or otherwise, within the consensus process.5 (Many decades ago, feminist Jo Freeman called this tendency the tyranny of structurelessness.)

I like to think of this phase as one of the most fruitful and important ones: when we try to change systems and see their very re-creation within our alternatives, we gain greater insights into how capitalism and its ideologies live within us and around us, and what is needed to transform them.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

From this place, organizations can get mired in conflict, taking personal responsibility or blaming others for not having changed everything. This can result in individuals within organizations attacking themselves and each other for not being “principled” or “radical” enough or in some way “doing it wrong.” If drawn into these patterns, the liberatory organizational change the group was aiming for becomes fragile and tenuous. At times, the changes are abandoned for a return to the former status quo or insurmountable fractures are created that result in groups dissolving or individuals being forced to leave.

Alternatively, organizations can recognize that the new challenges arising from the dialectical process of change are an inherent condition of prefigurative politics—there is no way through but through. This recognition and acceptance can lead groups to the leading edges of experimentation.

These two cycles can be reflected visually, as below.

Four Examples

To ground these cycles in practical realities, we offer some examples from our community of practice. We offer these insights from a position of transparency and vulnerability in hopes that they will be of service to the broader movement ecosystem.

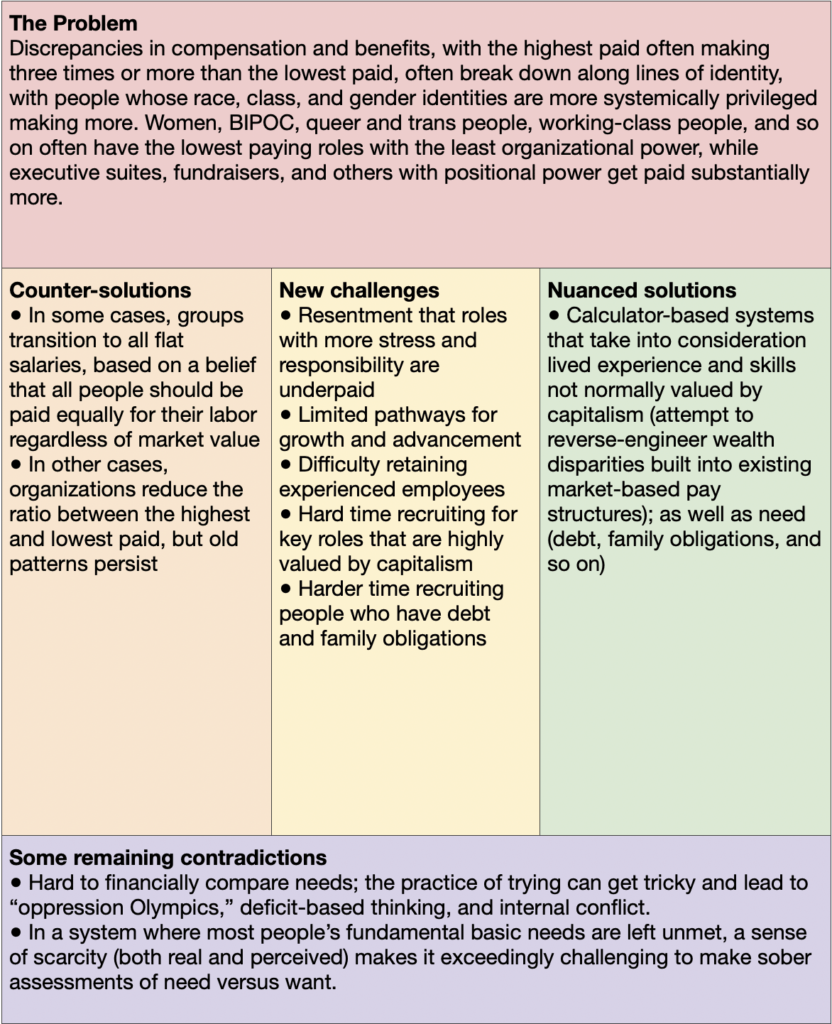

Compensation

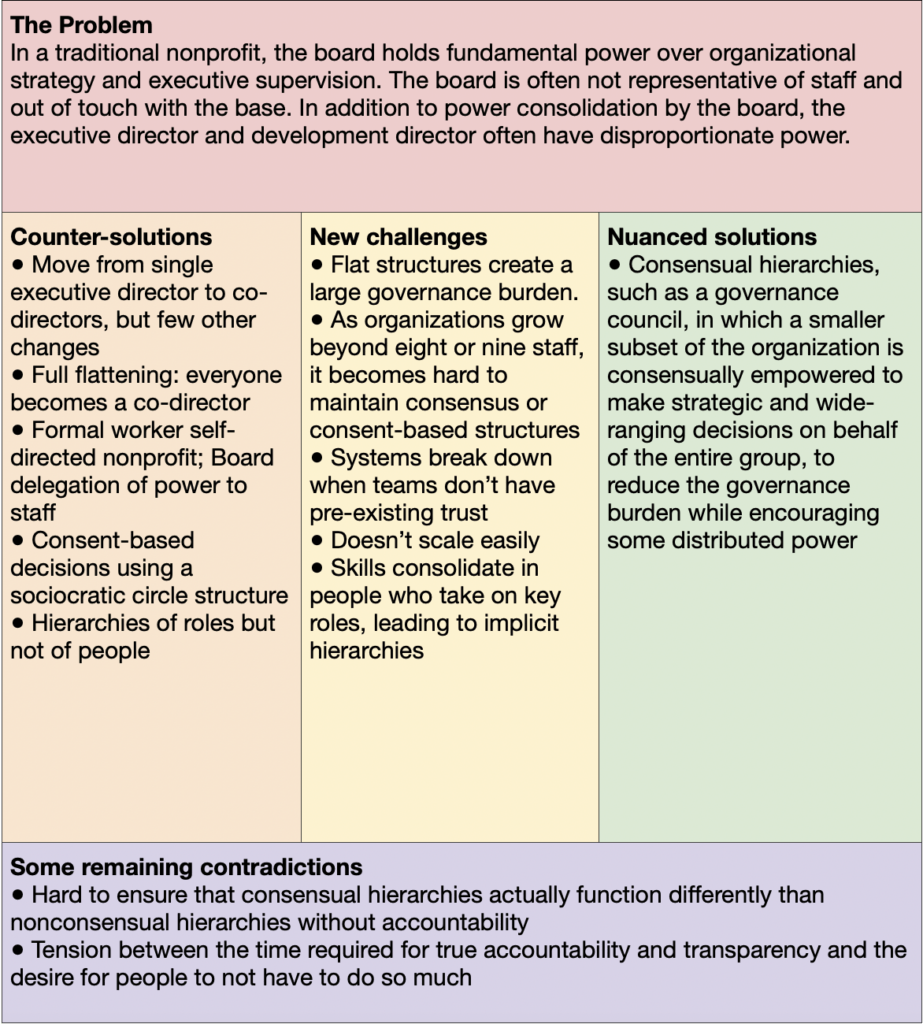

Power Sharing

Conflict Transformation

Leadership Development

Maturing a Resilient Movement Ecosystem

As we practice self-governance in our organizations, we prepare ourselves for broader liberatory work.

What the evolving practices highlighted above represent, across movement organizations and activists, is a maturation from reaction to vision. It turns out it is much easier to critique something and then try its opposite (implement a “counter-solution”) than it is to methodically create something that is aligned with all our values, which at times can be competing or contradictory.

The practice of self-governance requires a rejection of purity politics. Liberation is an active, daily practice. There is no holy grail. It matters that we try.

As we practice self-governance in our organizations, we prepare ourselves for broader liberatory work. After all, if we cannot self-govern in relatively small organizations, how will we claim power and govern at the scale needed to build the more beautiful world we know is possible?

Returning to Kaba:

People want to treat “we’ll figure it out by working to get there” as some sort of rhetorical evasion instead of being a fundamental expression of trust in the power of conscious collective effort.

You don’t need to have all the answers. But it helps to have a community to experiment with, the ability to hold nuance and complexity, and a belief in the importance of practicing freedom. Perfection is not the goal; practice is.

To learn more about the Nonprofit Democracy Network or join our community of practice, reach out to nicole@nonprofitdemocracynetwork or visit our website.

Notes:

- For an exploration of other models, see Michael Haber, “The New Activist Non-Profits: Four Models Breaking from the Non-Profit Industrial Complex” University of Miami Law Review 73, no. 3 (2019). https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol73/iss3/6

- Ella Baker, “Minutes/Summary of Civil Liberties-Civil Rights Conference,” June 28–30, 1963, Atlanta, GA, Braden Papers, box 47, folder 9, SHSW. Cited in Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 290.

- For historical examples of this movement capture, particularly of the Civil Rights movement, see: Megan Ming Francis, “The Price of Civil Rights: Black Lives, White Funding, and Movement Capture,” Law & Society Review 53, no. 1 (2019), 275–309; Karen Ferguson, Top Down: The Ford Foundation, Black Power, and the Reinvention of Racial Liberalism, (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013); and Robert L. Allen, Black Awakening in Capitalist America; An Analytic History, (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969).

- Mariame Kaba, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice, (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2021).

- “Rank” is a term I draw from process-oriented psychology that refers to a person’s relative positional power. Rank often includes aspects of what racial justice discourse calls “privileged” and “marginalized” identities (race, gender, disability, class, sexuality, and so on). It also includes aspects of power that can be conferred upon an individual for other qualities, including personality and role within the organization. Rank recognizes that positional power changes from context to context.