January 25, 2020; Valley News

From coast to coast, a network of more than 5,000 programs blends funding from federal, state, and local government with just enough philanthropic support to serve nutritious meals to more than two million people each year. That’s the recipe that has kept Meals on Wheels operating for more than 70 years. Increasingly, with lagging support from the governments, this recipe is coming up short.

The wisdom and cost effectiveness of home-delivered meals for seniors was first identified by a group in Philadelphia in 1954, at a time when the nation was focused on poverty and the plight of aging Americans. Founders saw a program model working in Great Britain and built on it to meet the specific conditions they found in their city. From this seed grew a model that could be replicated and adapted in to meet the needs in cities, towns, and rural communities.

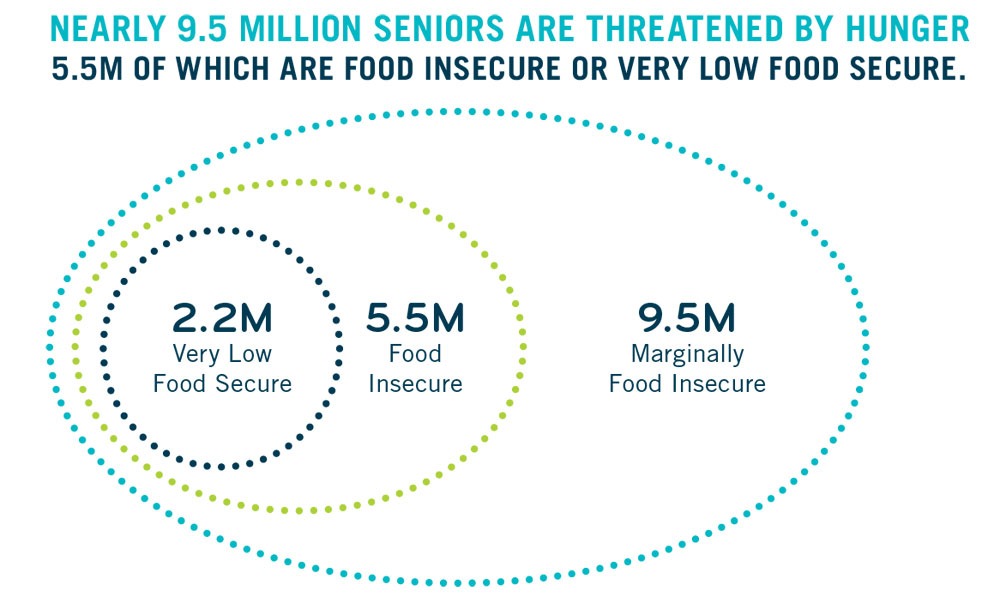

In the beginning, the challenge was to get the public’s attention and move government and philanthropy to provide resources. When Meals on Wheels launched, one quarter of the nation’s senior population lived in poverty and faced food insecurity. Today, according CBO data, the senior poverty rate has fallen by more than by 70 percent, but millions of seniors remain food insecure. Meals on Wheels programs remain critical to those they serve, but funding is a continuing challenge.

Three separate federal programs―Medicaid, Social Service Block Grants, and Older Americans Act Grants—provide funding to states so they can allocate it to local programs. Federal funding, which on average provides about only 35 percent of the cost of service at current levels, has not grown to keep pace with the need.

Nonprofits will be familiar with this quandary. Government contracts create a budget deficit because they almost never cover full costs; they require fundraising in equal proportion to the contract amount, even in the best of circumstances—and those aren’t the ones we have. For the Trump administration, funding Meals on Wheels has been anything but a priority. Supporting a budget proposal that decreased federal funding for Meals on Wheels, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said, “We can’t do that anymore. We can’t spend money on programs just because they sound good. And great, Meals on Wheels sounds great.”

With a human need before them, states, counties, cities, philanthropies, and local nonprofits are left to fill the gap if they can. Each Meals on Wheels program is different; they budget and operate independently. In New Hampshire, local programs served almost 100,000 more meals than state contracts were able to support, forcing local government and nonprofit organizations to draw more $3 million dollars from other sources. According to a recent story in New Hampshire’s Valley News, demand for meals has outpaced federal funding.

Jaymie Chagnon, executive director of Strafford (County) Nutrition & Meals on Wheels, told the Valley News during an interview that the agency expects to exceed its state contract by 12,000 meals.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“That doesn’t mean those people aren’t eligible. It means I’m serving what the state won’t reimburse me for,” she said. “We can see that the trend is growing.” The New Hampshire legislature is currently considering whether it can provide $450,000 more, but there’s no data to say that amount will be sufficient.

When additional funds cannot be found, each local organization must decide whether to impose waiting lists, establish a triage framework which prioritizes some clients over others, or reduce the number of meals served each week. Laura Ziemer, director of client services for the Waco Meals on Wheels, told WBUR’s Here and Now she wishes her team “didn’t have to make those decisions.”

Meals on Wheels America CEO and President Ellie Hollander told Here and Now, “We have mounting waiting lists across the country… people who aren’t even being added to a waiting list because there is no hope that they’ll be able to, in their lifetime, get off of one.”

Congress rejected the administration’s recommendation for a cut in funding, adding $15 million in new funding for home-delivered meals. This was a welcome level of new funding but not enough to fix the problem. According to data from Meals on Wheels America, private philanthropy has not prioritized this need either; less than two percent of philanthropy goes to seniors and the organizations that serve them.

The genius of Meals on Wheels is that it meets an immediate need and prevents deeper problems from arising. According to data compiled by Meals on Wheels America, “Eighty-three percent of low-income and food insecure seniors do not receive meals they may benefit from, due in part to insufficient funding. Poor nutrition among older adults often compounds existing health challenges…healthcare costs associated with malnutrition in seniors total $51 billion.”

Meals on Wheels also helps maintain seniors in their homes, reducing the need for expensive institutional care. As 93-year-old Betty Hanover explained, “It’s my big meal of the day and big excitement of the day.”

Each of the 5,000-plus Meals on Wheels programs serves as a canary in the nation’s human safety-net mine. They are examples of how government and civil society can partner on a very local basis to effectively help those in need. But nowhere near enough attention is being paid to the bind these programs are in, increasingly having to choose between serving those in need today and living to serve another day.—Marty Levine