September 21, 2020; New York Times

Over 56 million students attend K–12 schools in the US, including both public and private institutions, and approximately 3.8 million teachers teach them. While the majority of schools are teaching remotely, a sizable percentage, estimated at 25 percent, are providing in-person instruction. That’s 14 million students. And that does not include millions more who participate in some form of “hybrid” instruction.

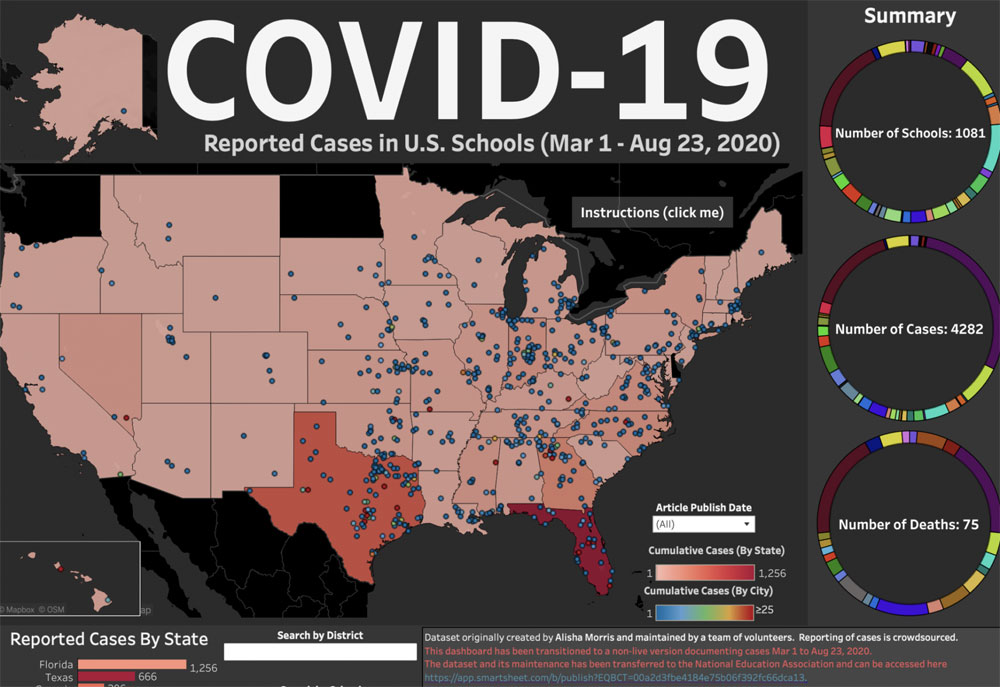

Now, we are weeks into a new school year amid a global pandemic that has killed almost one million people, including over 203,000 in the US. Yet as the New York Times reports, “there is no federal effort to monitor coronavirus cases in schools.” States are inconsistent or nonexistent in reporting their own data, with 11 states reporting no data whatsoever. According to the Times, “it is nearly impossible to tally a precise figure of how many cases have been identified in schools.”

In order to counter this lack of data collection and reporting by the federal government, media and educational groups are establishing tracking databases, which, as we head into the winter months, are increasingly critical for families across the country. Currently, the New York Times, The COVID Monitor, and The COVID-19 School Response Dashboard are attempting to bridge this immense data gap, but their endeavors are not without difficulty, as well as discrepancies.

The New York Times is seeking to “collect data from state and local health and education agencies and through directly surveying school districts in eight states [but] just a quarter of the districts in these eight states responded to the Times survey and additional inquiries, meaning the data is far from comprehensive and most likely undercounts hundreds if not thousands of cases.” Furthermore, some districts who were contacted simply refused to provide any information, and some punted the questions to state and local officials. Others responded that they weren’t tracking at all.

The inconsistency in districts’ willingness to report data isn’t the only challenge. The actual components of the data, as to what is and is not counted, are inconsistent, too. Some schools surveyed only started counting cases once they opened for in-person instruction. Others count students and staff based on symptoms rather than actual positive tests. Some count student cases but not teachers or staff, or vice versa, or included bus drivers and cafeteria workers where others did not. The Times found that as of September 21st, for all the states who are currently reporting cases in at least some capacity, there are almost 14,000 cases in K–12 schools. But as they point out, this number is a minimum, as many cases are never counted.

The estimate in the Times is significantly lower than what is being reported by The COVID Monitor, which claims there are over 27,000 cases in US elementary and secondary schools. This database is a collaboration between FinMango and COVID Action, using data sourced from state agencies, the media, and public reporting drawn from an anonymous form where parents, students, and teachers can contribute. Despite reporting a larger number of cases than the Times, the Monitor’s data draws from a smaller state pool, claiming that 17 states are fully reporting data and only seven are providing limited data, which differs from what the Times claims.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The other K–12 tracking database, as NPR reports, is the recently established COVID-19 School Response Dashboard, which was “created with the help of several national education organizations. Right now, it shows an average of 230 cases per 100,000 students, and 490 per 100,000 staff members, in the first two weeks of September. The responses come from public, private, and charter schools in 47 states, serving roughly 200,000 students both in person and online.”

How to make sense of these numbers? According to Anya Kamenetz and Daniel Wood of the New York Times, the student rate works out to the equivalent of a daily case rate of 16.4 cases per 100,000—the next-to-highest risk category as set by the Harvard Global Health Institute and the Brown University School of Public Health. The staff rate works out to the equivalent of a daily case rate of 35 cases per 100,000—in other words, in the highest risk category. Kamenetz and Wood caution, however, that these numbers are based on early and incomplete data.

Though the dashboard only has 653 school participants so far, the expectation is that more will participate in the future. Emily Oster, a Brown University economist, led the effort because “other people weren’t doing it,” and she has been joined by the School Superintendents Association, the National Association of Elementary School Principals, the National Association of Secondary School Principals, and other groups representing charter and independent schools.

Oster says this dashboard differs from The COVID Monitor in that it also includes infection rates in addition to raw case numbers. However, as noted by Danielle Zerr, a pediatrician at Seattle Children’s Hospital and a professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington, Oster’s project “is useful only relatively speaking, in the context of the general lack of a robust national testing, tracing or data-collection effort for schools.” The same could be said for the Times and the Monitor: “There’s nothing systematic, that I’m aware of anyway, to really evaluate how we bring children back safely.”

The Trump administration forcefully pushed for opening elementary and secondary schools, deeming it necessary for the economy to reopen and to undo the learning deficit created by school closings at last year. Beyond the over seven million coronavirus cases in the US and the growing number of deaths, the lack of standardized tracking of cases in K–12 schools is highly problematic. Almost one-third of elementary and secondary school teachers in the US are over 50, and of the 11 states not reporting any statistics according to the Times—excepting Maryland for which there was no data—eight of 10 exceed the national average of teachers over 50. As stated by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), “Among adults, the risk for severe illness from COVID-19 increases with age, with older adults at highest risk.”

Furthermore, over half of US K–12 students are students of color. And though studies show that deaths among white Americans have increased nine percent since the start of the pandemic, as recently reported, that number is “more than 30 percent for communities of color.” And we are heading into the cooler fall and winter months, which, according to recent research by Johns Hopkins University, will most likely increase the spread of the virus.

Despite the crucial data collection work these media and educational organizations are doing, without standardized methods of reporting, actual consistency regarding the data schools are collecting, and a federal mandate requiring K-12 schools to report infections like hospitals, millions of students, teachers, staff, and their families will remain in the dark as to the prevalence of COVID-19 in their schools and to their potential risk of exposure to infection.—Beth Couch