July 29, 2018; San Jose Mercury News

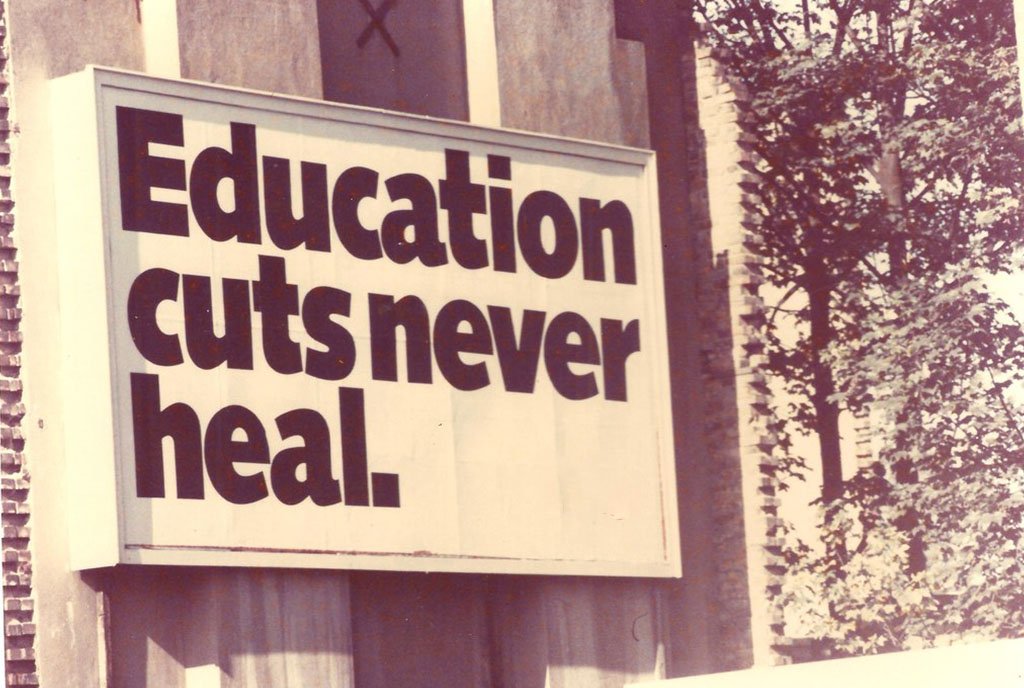

For at least 50 years, writes Carolyn Jones in the San Jose Mercury News, California students “have spent time during 4th grade learning the state’s history, with a focus on the Spanish missions—the 21 outposts established by Father Junipero Serra, soldiers and settlers in the late 1700s and early 1800s.” The outposts were established as a means for the Spanish conquerors to control the area’s original American Indian population and convert American Indians to Christianity. As the California Missions Foundation explains:

In the missions, Native Americans received religious instruction and were expected to perform labor, such as building and farming for the maintenance of the community. It was a life that was dramatically different from the life they knew before the Mission era…. Missionaries discouraged aspects of Native religion and culture.… Corporal punishment, such as floggings, for Native Americans who disobeyed the rules was frequent and at times severe.

The Missions Foundation adds, “Whatever the modern view of the missions, one thing is clear: California Indians built each mission and it was California Indians who lived, worked, and died in them.” And while California today has relatively few American Indian residents—the Census reports that 1.6 percent of state residents are American Indian or Alaska Native and another 0.5 percent are Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander—the state once had a high concentration of American Indian residents.

Yet American Indians are sidelined in the traditional historical account nonetheless. As Rose Borunda, an education professor at Sacramento State University and a coordinator of the California Indian History Curriculum Coalition, explains, “For so many years, the story of California Indians has never really been part of classrooms. Our story has never been present. It’s often sidestepped because it’s inconvenient. But it’s the truth, and students should learn it.”

As Jones details, prior to Spanish colonization, “Native Californians numbered more than 300,000 and had more than 200 tribes, dwelling in almost every part of the state.” While 300,000 may not seem a high population today, it is more than three times California’s population in 1850 at the time it gained statehood and became the nation’s 31st state.

Borunda, who hails from the Purepecha nation, and her colleagues “are working to educate teachers statewide on the history of California’s indigenous people, who were among the most populous and diverse Native Americans in North America.”

The changes, notes Jones, “are part of a broader effort to expand Native California curriculum in the state’s K-12 schools.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In 2016, when the state updated its History-Social Studies framework, the mission chapter was broadened to include more information about Native Californians, how they lived before colonization and how they were affected by the arrival of settlers.

“We changed it because it was the right thing to do,” says Nancy McTygue, executive director of the California History-Social Science Project at UC Davis, which oversaw the revisions. “It’s better history teaching. It’s more responsible. Whatever the topic, we wanted students to have a more nuanced understanding of the past, so they can make more informed interpretations.”

Gregg Castro, a member of the California Indian History Curriculum Coalition, notes that efforts to include the American Indian experience within California history have progressed by fits and starts since the 1970s. In some cases, little has changed. In others, American Indian nations have worked closely with local elementary schools to provide lesson plans and guest speakers to supplement the fourth-grade California history curriculum.

The topic is complicated, Castro explains, since California tribes spoke hundreds of languages and dialects and each had a culture adapted to the areas in which they lived: the desert, the mountains, the Central Valley, or the coast. Even more challenging is figuring out how to address the enslavement, disease, and slaughter of many American Indians. “It’s a difficult period in American history, and it’s especially hard to teach to nine-year-olds,” says McTygue.

One approach is to teach more broadly about the entirety of the 10,000 years of American Indian history in California, rather than solely focusing on the period of colonization.

Jones indicates that Castro also recommends having “elementary teachers look at broad topic areas, such as salmon or fire, and incorporate multiple academic subjects into their lessons. For example, a unit on salmon would include native traditions and lore about salmon, as well as lessons on the fish biology, river ecosystems and seasons. A unit on fire would cover how native people burned fields to enrich the soil, manage vegetation to attract wildlife and prevent larger wildfires. This unit would include lessons on ecology, land management and how humans alter their environment.”

“It can be done quite well, in a non-traumatizing way, without shading the truth,” says Castro. “Right now, there is abysmal ignorance out there because people just weren’t taught about Native Californians in school. But people need to know this. They need to know what happened, that we’re still here, that there are still things to be saved.”—Steve Dubb