March 13, 2018; Washington Post and NPR

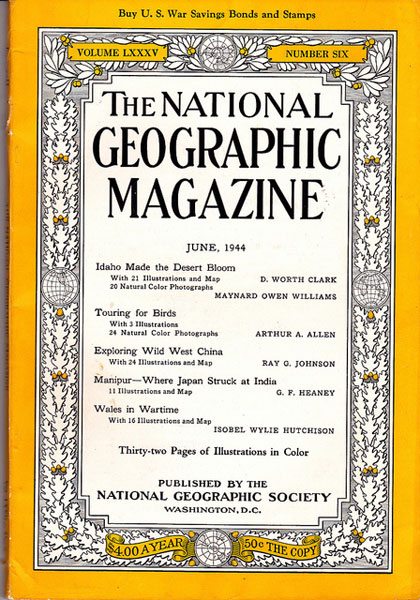

The publication of the April 2018 issue of National Geographic has drawn much attention for its focus: the 130-year-old magazine’s self-examination of its history of racism. For those who have long gazed at the depictions of black- and brown-skinned natives of other continents on the pages of this highly respected journal and admired the photography and the writing, the admission that both the photos and the writing were slanted and racist may now send many of us back to the piles of magazines stacked in attics and basements for another look. Could this also raise questions as to how our nonprofit work plays out over time? Looking at how National Geographic came to its self-examination reveals some interesting points.

Editor-in-Chief Susan Goldberg titled her personal introduction to the April issue of the magazine, “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise Above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge It.” And even this introduction has met with mixed reactions.

It was an extraordinary concession from the magazine. Renowned for its photography and its coverage of science, history, anthropology and the environment, National Geographic has also faced criticism over the years for reporting on the world through a narrow, white, Western lens.

Breanna Edwards of the African American-focused news and culture site The Root called the move “the first step to righting a long-overlooked and perhaps even taken-for-granted wrong.”

“Bluntly acknowledging its own past in this way is indeed powerful, but it is not necessarily something, I think, that we should applaud, as much as we should expect,” Edwards wrote, “especially at this time in our lives when race and discussions of racism and even general cultural insensitivity can be volatile, tense and perhaps even deadly.”

Others were more critical, including Vox’s Kainaz Amaria, who tweeted that the magazine’s “colonial visual legacy” had, in effect, trained nonwhite, non-Western people to allow themselves to be “exploited and otherized.”

In a move to insure credibility for National Geographic’s commitment to its own admission and study of its racist past, it brought in John Edwin Mason, a University of Virginia professor specializing in the history of photography and the history of Africa, to do a deep dive into the magazine’s past. His findings, according to Goldberg’s introduction to the issue and in interviews with Mason himself, found an editorial slant at the magazine that ignored people of color in the United States and focused on native populations in Africa and Polynesia who, Goldberg wrote, were shown “as exotics, famously and frequently unclothed, happy hunters, noble savages—every type of cliché.”

Goldberg and Mason also found that National Geographic was racist in what it omitted from its coverage. A 1962 article on South Africa neither quoted black South Africans nor mentioned the massacre of 69 black people by police in Sharpeville 2½ years earlier.

“That absence is as important as what is in there,” Mason said in Goldberg’s piece. “The only black people are doing exotic dances…servants or workers. It’s bizarre, actually, to consider what the editors, writers, and photographers had to consciously not see.”

Until the 1970s, National Geographic did little to challenge stereotypes in white American culture, Mason found.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“National Geographic wasn’t teaching as much as reinforcing messages they already received and doing so in a magazine that had tremendous authority,” he said. “National Geographic comes into existence at the height of colonialism, and the world was divided into the colonizers and the colonized. That was a color line, and National Geographic was reflecting that view of the world.”

The pain in putting themselves out there for all to examine is clearly felt in Goldberg’s writing. But the hope for where National Geographic will go from here is also what stimulated this issue and what is indicated as a year-long examination in future issues of the magazine.

“The coverage wasn’t right before because it was told from an elite, white American point of view, and I think it speaks to exactly why we needed a diversity of storytellers,” Goldberg told the Associated Press. “So, we need photographers who are African American and Native American because they are going to capture a different truth and maybe a more accurate story.”

But for National Geographic, the pain in this process continues as their cover story, depicting American mixed-raced twins, one dark-skinned and one fair-skinned stimulated further controversy, including an opinion piece in the Washington Post by Victor Ray, a sociology professor at University of Tennessee Knoxville.

The cover photo depicts 11-year-old mixed-race twin girls, with the tabloid-esque framing that one is black, the other white. And the headline makes the grand claim that the girls’ story will “make us rethink everything we know about race.”

The “we” here is implicitly white people, and the story of these children doesn’t break new ground so much as reinforces dangerous racial views. The girls in the photo, with their differing skin tones, are depicted as rare specimens and objects of fascination.

Admittedly, my problems with this article are both personal and professional. I’m a light-skinned black man who grew up with my darker-skinned younger brother. We were likely candidates for this type of story.

…And my personal experience leads me to suspect that much of the “curiosity and surprise” that greet these young women come from white people. Black people are aware that we come in all shades.

In seeking to tell its story, did National Geographic still err on the side of its historic white perspective? Is this yet another lesson to be learned for the magazine and for those in the nonprofit sector who seek to change?

Some will only see the flaws in the efforts, and others will see value. Either way, there will be challenges. National Geographic could not continue as it had. It had the reputation and resources to take on the challenge. It has shown leadership, in its own way, for others to follow. Its future issues will demonstrate just what its commitment is. But, as Victor Ray states as he closes his opinion piece, “If National Geographic really wants to atone for its racist past, it should drop narratives that overstate the racial progress we have made and stop misrepresenting racism as a personal sin.” Can nonprofits do the same?—Carole Levine