April 19, 2017; Philadelphia Inquirer

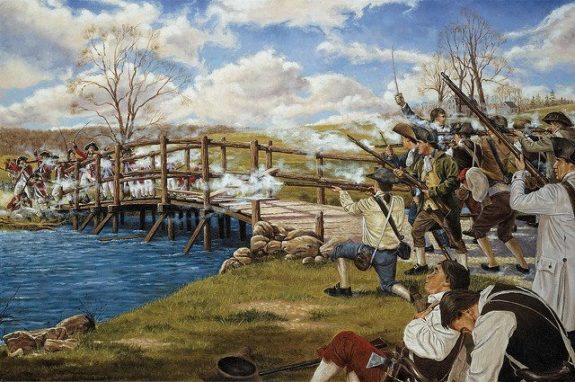

On April 19th, 242 years to the date after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the 18th-century revolution and subsequent war that led to the founding of the United States finally got a museum dedicated to telling the stories of those times, and to asking questions expected to resonate still with 21st -century visitors. The $120 million Museum of the American Revolution, nestled in the heart of Philadelphia’s historic district, opened with great fanfare and with thoughtful tributes to those who lost their lives for the cause of independence, and to the common men and women—including immigrants, Native Americans and slaves—whose stories are often overlooked in the history books.

The opening-day ceremonies began a few blocks from the new museum with a prayer service and remembrance at the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier in Washington Square, “a six-acre green that was and remains a burial ground for thousands of unknowns who lie beneath its paths—soldiers of the Continental Army, British troops, American Indians, black people, both freed and enslaved.” Next came a parade—heavy on fifes and drums—in front of Independence Hall, with color guards and military reenactors in period costumes ranging from formal to rag-tag from each of the original thirteen colonies (along with governors, lieutenant governors, and former governors from seven of the 13). Finally, a 90-minute series of speeches and performances filled the courtyard outside of the brick-faced building designed by Robert A.M. Stern Architects. Among the highlights:

- Remarks by noted author David McCullough, political commentator Cokie Roberts, former Vice President Joe Biden, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf, Col. John E. Bircher III of the Military Order of the Purple Heart, Harvard University history professor Vincent Brown, and Ray Halbritter of the Oneida Indian Nation

- Performances by a brass quintet from the Curtis Institute of Music and the Philadelphia Boys Choir, plus two crowd-pleasing songs from Hamilton, featuring original cast member Sydney James Harcourt and students from Philadelphia’s High School for the Creative and Performing Arts—all within shouting (signing?) distance of Alexander Hamilton’s First Bank of the United States

- An official ribbon cutting—using a sword—by a convincing simulacrum of General George Washington himself.

Of course, other museums and monuments up and down the East Coast and elsewhere mark important sites and moments in the American Revolution. The new museum—which describes itself as “a private, nonpartisan and nonprofit organization”—is just blocks away from Independence Mall, the National Constitution Center, and dozens of other pivotal sites that date back to or otherwise commemorate the nation’s founding. But this is the first museum fully dedicated to the history of the American Revolution—from the decades of discontent that preceded the war through the thorny challenge of what to do with independence once it had been won.

As noted in an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer a few days before the museum opened, the backstory for this particular museum is long and sometimes twisted. Originally, it was intended for Valley Forge, where George Washington and his troops famously camped and where the Valley Forge Historical Society and its 500 or so Revolutionary War objects—the foundation for the museum’s collection—were based.

How these 3,000-plus artifacts—including Washington’s tent, or “marquee,” as it is formally termed—found their way from Valley Forge to Philadelphia, where 400-plus of them will be on display, is a modern saga of political and civic muscle that began in the 1990s. Traveling the 22 pothole-pitted miles from the old historical society digs to Philadelphia’s historic district took far longer than the Revolutionary War itself, which lasted a mere eight years, from 1775 to 1783.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The museum is meant to draw visitors into the excitement, the fear, the moments that shook the faith of the revolutionaries or steeled their resolve. The core exhibits fill 16 galleries and are designed to address four questions—and to challenge visitors to consider their personal responses to them:

- How did people become revolutionaries?

- How did the revolution survive its darkest hours?

- How revolutionary was the war?

- What kind of nation did the revolutionaries create?

In one New York Times article ahead of the opening, R. Scott Stephenson, the museum’s vice president for collections, said that the immersive and interactive exhibitions and the questions they pose are more typical of what might be found in a science museum, not a history museum. In a second Times article, a gallery titled “Resistance,” dedicated to the years between 1765 and 1775, is described as being “dominated by a huge re-creation of a ‘liberty tree,’ where citizens would gather to debate taxation, trade and other issues.” Stephenson said the gallery’s tree might be considered “the great-great-great-great-great-grandmother of Occupy Wall Street.”

Throughout the museum, which of course celebrates well-known Founding Fathers, emphasis is placed again and again on the stories of common men and women and unsung heroes like the Oneida Nation, the only Native Americans who took the side of the colonists in the American Revolution. The messiness of the Revolution, the disparate views of its participants, the tenuous position of the Continental Army through much of the war—all are exposed and celebrated as part of the larger story. As Jennifer Schuessler wrote for the Times, “If it doesn’t quite throw the old heroic narrative out the window, it does draw on decades of scholarship that has emphasized the conflicts and contradictions within the Revolution, while also taking a distinctly bottom-up view of events.”

Several opening-day speakers noted how relevant the museum is at this moment in the nation’s history and how important it is that Americans understand the struggles that led to—and continue to define—democracy. In his remarks, David McCullough said, “What a morning to be grateful to be an American…The American Revolution still goes on.”—Eileen Cunniffe

CATEGORY:

TAGS: