April 14, 2019; New Orleans Advocate

Last week, in the historic (and historically black) Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, the city’s African American Museum officially opened its doors to the public after a six-year closure. Or, to be more precise, part of the museum—one of its five buildings—reopened to the public (with limited hours) following a $2 million renovation. People lined up outside the entrance, on the steps, and all along the sidewalk in front of the building to celebrate the reopening, suggesting a high level of public enthusiasm for the museum.

So, what is behind the re-reopening—or more importantly, the repeated closures—of a nonprofit cultural institution that debuted in 1998 but has since been shuttered twice, in each instance for several years at a time? As reported in the Advocate, the museum’s (relatively brief) history has been marked by a “pattern of financial and management challenges”—some of which will sound at least vaguely familiar to many nonprofit leaders, while other challenges, like storm damage from Hurricane Katrina, represent just plain rotten luck.

In its first incarnation, a 19th-centruy Creole mansion was renovated “both to highlight local African-American history and to spur economic development in the struggling Tremé neighborhood,” according to the Advocate article. Then-mayor Marc Morial may however have missed the fine print that came with a $1.2 million federal grant that paid for the renovation, because those funds also were applied to the museum’s operating expenses during its first six years. Morial set up a nonprofit to grow the museum and took over several adjacent buildings, with the intention of expanding the cultural entity into a complex. However, when the US Department of Housing and Urban Development learned how its funds had been used, it demanded—from by-then mayor Ray Nagin—a $1 million refund. The museum was broke, and its doors closed for the first time in 2003.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Despite significant damage from Katrina in 2005, the expanded museum reopened in 2007, and stayed open for another five years, at which time the executive director was fired, revenues were found to be precipitously low, and no funds were available to repair the damaged buildings. So, the museum closed again. Subsequently, a local real estate investor stepped in to help repay a $1 million loan the museum had taken from a now-failed bank, but that arrangement later fell apart.

Of course, many cultural institutions struggle to balance their budgets, to raise funds to renovate or repair aging facilities, and to maintain collections. Historical museums struggle even more than other types of institutions, and black history museums often face even bigger challenges. It is fair to say That there has been a relative dearth of capital dedicated to advance the work of African American museums in the US since NPQ’s Rick Cohen in 2014 wrote an in-depth, two-part feature on these funding disparities and their effects on the field. And it would be impossible to understate the impact Hurricane Katrina had on the infrastructure, the funding landscape, and the civic and cultural priorities faced by local leaders in New Orleans in the wake of that catastrophic storm.

And yet, even allowing for all of these usual and oh-so-unusual challenges, it’s impossible not to wonder who was minding the shop—and most specifically the books—for the New Orleans African American Museum at the outset of this cultural institution’s life. Perhaps even more importantly, who was providing oversight before and after it opened for the second time, when New Orleans was still reeling from Katrina? Who were its leaders—board and staff—and what kind of planning and oversight systems did they have in place? Who were the funders and were they included in conversations about the museum’s facilities, its programs, its budgets? Two such lengthy closures, which together account for roughly half the museum’s total lifespan, suggest significant lapses in governance and leadership over the years. At the very least, those in positions to do so seem to have avoided asking—or insisting on answers for—the most difficult questions.

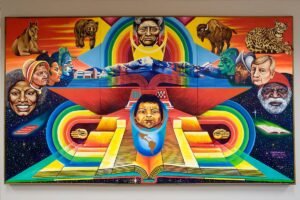

The museum has hired a new curator and executive director, and the board is described as having “a dozen mostly new members,” as well as a national advisory committee, led by Morial, who is currently president and CEO of the National Urban League. But only the one building is open, and only for 15 hours each week (11 am to 4 pm Thursday through Saturday). And to restore and open the other buildings, the organization will need at least another $12 million. The museum website touts the permanent collection as well as the surrounding gardens and courtyard. The public seemed eager to show its support last week for the (latest) opening celebration.

But will this third opening “stick”? Let’s hope it does.—Eileen Cunniffe