Taiwana lived in Flint, Michigan, in 1996, in a home her grandparents had passed down through her family. She was in that home with six of her seven children when her rapist attacked. She had a job interview the next day and had woken up in the night with a feeling that something wasn’t right. As she checked the house, a man appeared in the darkness; though she fought back fiercely, she was assaulted, and one of her fingers was nearly severed in the fight.

Although she reported her attacker and got a rape kit, her case was not pursued for over two decades. Taiwana says the clerk at the police department was evasive about her attacker being in police custody; she saw him again, and eventually moved with her children to Syracuse, New York to get away from memories of abuse. “I was hurt, I was insulted,” she says, when she realized that police had virtually ignored her.

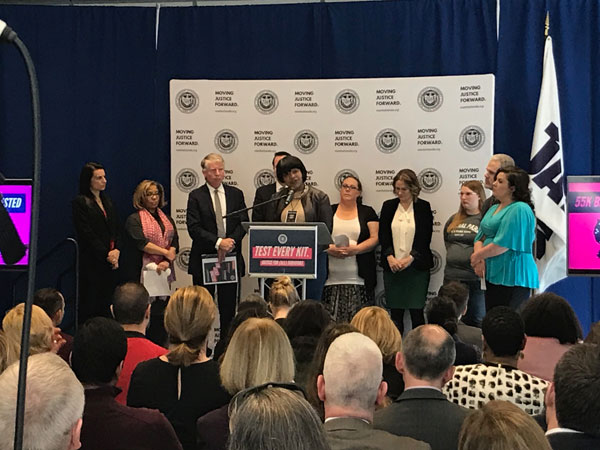

“I don’t know what you all in law enforcement are going to do,” Taiwana told the audience at a recent summit at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “We’re being exploited, survivors are being exploited…how many times do I have to do it your way? I don’t want to do it your way anymore.”

Tens of thousands of people have had an experience like Taiwana’s: After being raped, they go to a hospital and undergo the invasive and sometimes retraumatizing exam necessary to collect what’s known as a rape kit or a sexual assault kit (SAK), containing DNA evidence of the crime. Then their kits sit in storage units for months, years, or even decades, untested and forgotten.

The Joyful Heart Foundation (JHF) is leading a national effort to end this pattern, to make sure every kit is tested and, if possible, the case pursued. It’s estimated that hundreds of thousands of rape kits sit ignored on shelves across the US, but because most jurisdictions don’t even count or track the kits, there’s no way to know for sure.

Ilse Knecht, the Policy and Advocacy Director for Joyful Heart, said, “We always come down to the fundamental thing, which is that an individual survivor has gone through a sexual assault, probably the most terrible experience of their life…We need to do everything we can, as a society, to bring them a path to justice and healing. And part of that is testing their rape kit.”

Testing the kits makes it easier for the criminal justice system to pursue rape cases because of the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). When the kits are tested, the DNA is uploaded, and can be matched to profiles of people who have prior convictions or outstanding investigations.

Joyful Heart Foundation is a small but mighty operation. They have seven staff members, and until 2015, an annual revenue of less than $5 million. Yet they’ve managed to influence dozens of jurisdictions across the country to pass laws and spend money to get rape kits tested and bring justice to survivors.

Knecht said that because they don’t have the resources to hand-hold legislators and advocates through drafting and passing bills, they focus on producing tools such as draft legislation that can be widely available. Their six pillars of legislative reform include things like mandatory testing of kits and victim notification systems.

In 2014, the Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance announced the Manhattan District Attorney’s Sexual Assault Kit Backlog Elimination Program. Joyful Heart was part of that effort; founder Mariska Hargitay joined Vance at the announcement. The DA’s office had secured $800 million in civil asset forfeiture funds from settlements with international banks that had violated US sanctions, and committed $38 million to the grant program.

Between September 2015 and September 2018, according to the DA’s office, 32 jurisdictions in 20 states received funding. Between them, they tested over 55,000 rape kits, which has so far resulted in nearly 10,000 “hits” in CODIS and 186 arrests. In March, they held a summit at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice called “Testing Every Kit” in which they reviewed results and lessons from the program.

The Manhattan DA’s office says it developed the “forklift” approach, which is to test every kit, regardless of how long it’s been on a shelf, whether a victim cooperated with law enforcement, or the perceived weakness of the case. That’s a powerful commitment; one thing that can discourage survivors from coming forward is the knowledge that prosecutors often decline to pursue rape cases because they are perceived as difficult to win. The DA’s office also developed a strategy known as a “John Doe” indictment, in which they indict a DNA profile even if there’s no name attached to it. When they do that, because a case is already open, a future hit in CODIS can trigger prosecution even if the statute of limitations would have expired since the incident.

District Attorney Vance called the backlog of untested rape kids a “decades-long, systemic denial of equal rights.”

Joyful Heart works with victims, advocates, and legislators across the country to replicate this kind of effort. Knecht says her organization looks at the legislative landscape to see where there’s momentum: maybe a legislator who’s expressed interest in this issue or made a campaign promise has been elected, or a high-profile case drew the attention of enough lawmakers in a particular locale for advocates to get an audience. She also gave significant credit to “strong survivors who have become legislative advocates on the ground,” and says that guiding people on their journey from victims, to survivors, to advocates, is an important part of Joyful Heart’s work.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Rape and sexual assault is a sensitive issue, though Knecht says she’s seen the discussion around it shift significantly in the last decade. Apart from helping survivors come forward, this shift has brought awareness to the ways in which the criminal justice system’s approach to sex crimes is inadequate. Trauma victims are often panicked, silent, or unable to string together a coherent narrative; in the past, this has prevented police departments form pursuing their cases.

Now things have changed. At the summit in March, the Manhattan DA’s office openly acknowledge that rape cases have to be treated differently, that law enforcement often receives “insufficient training” on trauma response, and “victim-centered interviewing techniques” can build trust and help the system bring justice.

John Adler, Director of the Bureau of Justice Assistance, pointed out that other DNA evidence like fingerprints on guns is always tested immediately, while rape kits sit for years or even decades. He acknowledged the disparity as a choice made by law enforcement that disproportionately harmed women.

Tracey flew from Arizona to tell her story at the summit in New York. On a date in 2002, she says, she was given a drink that made her woozy, then raped in a hotel room. “I thought, ‘just hurry up and please be done,’” she said.

I planned to just walk to my car, and just go home, but it was no longer an option…My ex-husband was sent to pick me up, and he insisted we call the police. I just wanted to leave…I was shocked, hysterical, and ashamed…It was later that I decided on my own to obtain a rape kit. I was never offered, at the scene, to get a rape kit by the responding officers, nor was I even contacted by a detective after. Years passed; life moved on, and I mourned losing the carefree, almost naive part of me. I recognized rape as part of my story, and I closed the chapter.

Fifteen years later, in February 2017, a detective and a victims’ advocate knocked on her door, explaining that her rape kit had been tested and DNA was identified. Her attacker was accused by eight women and charged with 21 counts of sexual assault. “We are so happy that we got the justice we sought, that was long awaited,” Tracey said. “I know there are many others out there that never received that reward. Having my kit tested was a catalyst for hope.”

That hope is what Joyful Heart, the Manhattan DA’s backlog program participants, and many others wish to offer survivors through the justice rape kit testing can bring. Not only that, they say, but testing the kits can save money and heartache because catching perpetrators prevents future crimes.

“Rapists are often serial rapists,” said Knecht. “They commit all kinds of crimes, and they travel.” Matching tested kits to profiles has borne this out. Knecht said that Cleveland, for instance, estimated that they saved $38 million dollars by preventing the “future probable crimes” of the offenders identified when they tested 4,000 kits.

Taiwana, though determined to stay unaffiliated so as to maintain her independent voice, acknowledged that the shift in approach catalyzed by Joyful Heart and others in the way cases are handled was in the right direction.

“You need to get with [survivors] like myself,” she said, “not for camera shots, but for on-the ground work.”

Like many nonprofits, Joyful Heart and others have a long-term vision in which their work becomes obsolete. Knecht says she is working now on getting the six pillars of reform passed in each state, with transparent implementation and tracking systems. Then, she said, it’s on to reforming the statute of limitations.

Even that system isn’t perfect. Getting a rape kit means going to a hospital; pursuing a case means cooperating with the police. Knecht and others acknowledge that for many victims of rape, these two interactions are fraught with tension. But many expressed hope that through public commitments to end the backlog and educate people about how to deal with survivors of trauma, the system can become an avenue of justice for all survivors.

“Some survivors have said, it’s not until they got the DNA results that they felt they could breathe, but also that they felt like someone cared enough,” said Knecht.