December 11, 2017; Bloomberg

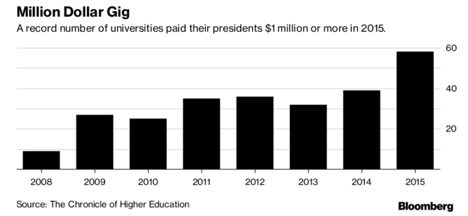

At a time when income gaps are increasing and the cost of higher education is a controversial issue, the compensation of university executives is a touchy, intersecting subject. An article from Bloomberg showing that the presidents of private nonprofit colleges receive increasingly large salaries, often a significant portion from deferred and potentially nontaxable income.

A study from the Chronicle of Higher Education showing data on more than 1,000 schools’ leaders dating back as far as 2008 showed that “average total compensation for school heads serving the full year was $569,932 [in 2015], up 9 percent from 2014’s average.” However, eight presidents of private schools earned over $1 million.

NPQ’s Michael Wyland noted in in March that “More than two-thirds of the nonprofits paying individuals more than $1 million rely on external compensation consultants to assist in setting base pay and total compensation…[but] nonprofits are learning what for-profits have known: Compensation surveys drive up executive compensation. No one wants to pay—or be paid—below the 50th percentile of compensation for similar organizations and similar work.”

It’s not just the base pay that drives upward competition. According to Bloomberg, “Total compensation includes base pay, bonus pay, nontaxable benefits (for example, health benefits, life insurance and dependent care) and other pay (such as severance payments, spending accounts and club dues). Such perks as housing and travel may also be included.” For instance, Arizona State University President Michael Crow earned $838,458 base pay, and over $15,000 in non-taxable income.

Where is all this money coming from? Some schools, especially private ones, have large endowments: Among private nonprofit universities, four of the Ivy League schools, plus MIT and Stanford, have endowments over $10 billion. The University of Texas system owns oil fields that generate up to $7,000 worth of oil per day, contributing to the largest endowment of any public university. Its president, William McRaven, is the second-highest-paid public university president.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But of the $603 million that the UT system drew from the oil fields this year, only $38 million went to student financial aid. Over $400 million went to systems administration and unrestricted funds.

Bloomberg reported,

As college presidents’ compensation has risen, so have tuition and student loan debt. In 2004, about $364 billion in student loans was outstanding. That figure has more than tripled to $1.3 trillion, according to the most recent New York Fed data.

That increase in debt has somewhat to do with decreased state and federal support. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities explained,

Overall state funding for public two- and four-year colleges in the 2017 school year…was nearly $9 billion below its 2008 level, after adjusting for inflation…Colleges have had to balance budgets by reducing faculty, limiting course offerings, and in some cases closing campuses. At a time when the benefit of a college education has never been greater, state policymakers have made going to college less affordable and less accessible to the students most in need.

Executive compensation is a tricky issue; it brings up questions of self-sacrifice for the cause, inflated overhead costs, and the responsible stewardship of donations and taxpayer money. David Cohen, chair of the board of trustees at the University of Pennsylvania, said, “The trustees believe she is the best university president in the country and that her salary should rightly reflect the stellar leadership she has brought to Penn.” At Wake Forest University, trustee chair Donna Boswell said, “President Hatch’s compensation over the course of his tenure reflects his exceptional leadership.”

Leading a university is a large and increasingly complicated task: as learning and job preparation evolve, government funding declines, and students demand more transparency of administrations, the role of president can be a difficult one. But Wake Forest’s Nathan Hatch earned over $4 million in 2015, and only 38 percent of his students received financial aid to a school that costs almost $50,000 just in tuition and fees. In light of the landscapes of both higher ed and income inequality, this is a situation that nonprofits may care to reexamine.—Erin Rubin