December 8, 2016; New York Times

In the midst of the Great Depression, historian James Truslow Adams defined the “American Dream.” He saw America as a land of promise for all, a nation where “life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.” While the overall economy has recovered from its 2007 plunge, the reality for too many households is that life is not actually getting better or easier and hasn’t for decades. The surprising election of Donald Trump as our next president spotlighted how deeply this loss of hope and increase in frustration has permeated our nation and how it has affected our national psyche.

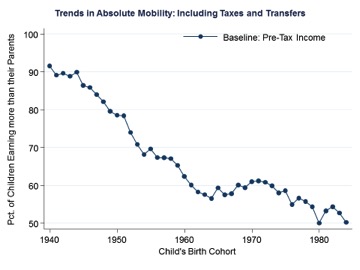

David Leonhardt, writing for the New York Times, looked at the work of a research team led by Raj Chetty, which has documented that this frustration is based in reality and not just the product of Trump’s rhetoric and the media. For those born in the 1940s, it was almost a guarantee that children would go on to do better economically than their parents: “About 92 percent of 1940 babies had higher pretax inflation-adjusted household earnings at age 30 than their parents had at the same age. (The results were similar at older ages and for post-tax earnings.)”

For those born 40 years later the story is very different.

For babies born in 1980—today’s 36-year-olds—the index of the American dream has fallen to 50 percent: Only half of them make as much money as their parents did. In the industrial Midwestern states that effectively elected Donald Trump, the share was once higher than the national average. Now, it is a few percentage points lower. There, going backward is the norm.

The causes of this decreased likelihood of improved household economy are varied and challenge policymakers who want to reverse this trend. Technological changes have reshaped the nature of the nation’s workforce. Many well-paid jobs in factories, mines and farms are no longer needed, replaced by more automated workplaces. Globalization has allowed work to leave the U.S. for places where employees earn less. The power of unions has decreased, limiting the workforce’s bargaining power.

But focusing solely on the comparison of earnings misses another important change in our economy. Over this same period, the gap between the very rich and the rest of the nation has grown dramatically. While the economy has grown dramatically and does have the potential to ensure a better life for all, the growing concentration of growth at the very top end of the wealth scale—the favored “1%”—makes improvement more and more difficult for the rest of the nation.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Professor Chetty’s research group “ran a clever simulation recreating the last several decades with the same G.D.P. growth but without the post-1970 rise in inequality. When they did, the share of 1980 babies who grew up to out-earn their parents jumped to 80 percent, from 50 percent. The rise was considerably smaller (to 62 percent) in the simulation that kept inequality constant but imagined that growth returned to its old, faster path.”

The election got our attention and drove home how badly the American economy is doing for so many. It’s not only the poor who are hurting, so changing course is now on everyone’s agenda. The question we must ask is, “What policies will actually work?” Is the future about rebuilding the economy of the 1940s with the kinds of jobs that made the American Dream come to life? Technology and globalization suggest this may not be possible; it may be that we need to ensure that the “safety net” we built reflects our “dream” for all who cannot find or get lucrative work. This makes the debate about the ACA, SNAP, and other social programs all the more important.

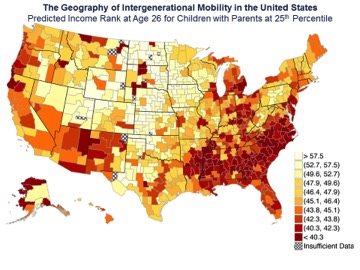

Chetty has also found significant geographic differences that may offer some clues to policies that will work.

The American Dream continues to thrive in some parts of the country. […] Differences in upward mobility across areas are caused by differences in childhood environment. Every year of exposure to a better environment improves a child’s chances of success, based on an experimental study of housing voucher recipients and a study of five million families who moved across areas.

David Leonhardt ended his look at Chetty’s data with this observation:

The painful irony of 2016 is that nostalgia and anger over the fading American dream helped elect a president who may put the dream even further out of reach for many people—taking away their health insurance, supporting ineffective school vouchers and showering government largess on the rich. Every one of those issues will be worth a fight. If the American dream could survive the Depression, and then thrive in a way few people imagined, it can survive our current troubles.

But, we would argue, only if we begin to develop networks of advocacy and alternatives to the current economic status quo from the grassroots up.—Martin Levine