May 22, 2017; Boston Globe

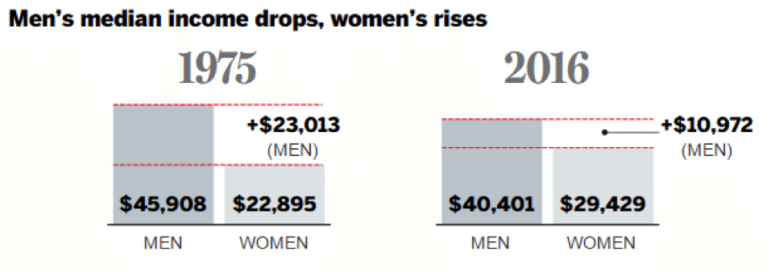

A recent study by the U.S. Census Bureau showed that the median income of American men between the ages of 18 and 34 is falling, but that of women is rising.

According to the Boston Globe, “The share of young men making between $30,000 and $100,000 a year shrank significantly over the past four decades, despite the fact that they are better educated and working full time at the same rate.”

During the same period of time (1975–2015), the number of young women in higher income brackets has grown. In 1975, less than two percent of women made more than $60,000 per year, in 2015 dollars; in 2015, 13.1 percent of them did. That’s still less than the proportion of men in the highest income bracket (23.5 percent of men make $60,000 per year or more), but the gap has shrunk significantly.

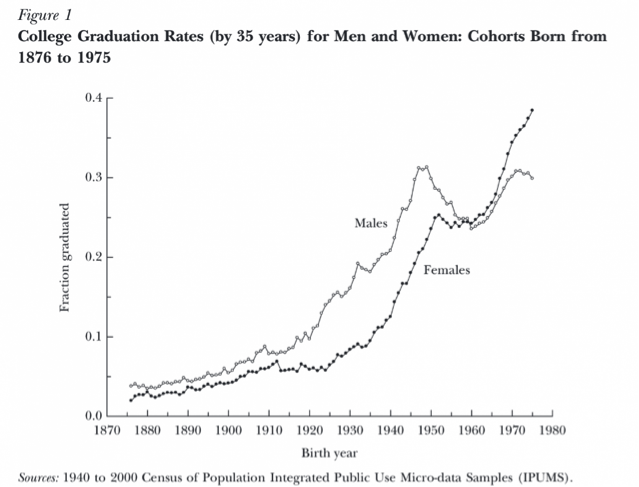

Women’s wages have risen slightly since 1975, but their educational attainment levels have risen significantly in that time. Seventy percent of women have a bachelor’s or an associate’s degree, compared to 36.6 percent in 1975, meaning that women’s rate of higher education has nearly doubled, compared to about a 20 percent increase for men, who now make up less than half of graduates from universities. (According to the Washington Post, “starting with people born in the 1960s, women have…graduated at higher rates than men.”) NPQ has reported on this dichotic gap between education and income, noting that it is particularly significant in the nonprofit field.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The upshot: both men and women have made significant gains in education, but only women have gained in earnings, and they haven’t gained enough to catch up with the average wage for men, whether measured today or 40 years ago. Among other concerns, that’s a problem for women’s equality and for the general financial welfare of American households.

Dozens of economic and social realities play into these wage trends, from family leave policies to the failure of wages to grow apace with inflation. The “Fight for $15,” which NPQ has closely followed, is not just a fight to recognize that the wealth gap has created great inequality; it’s a fight to recognize that real wealth has been lost in many households. Nonprofits are a part of this landscape, fighting the consequences of poverty while sometimes paying insufficient wages to their own staffs.

Part of what’s caused the disparity between men’s and women’s wage trends, according to the Boston Globe, is that “women are benefiting from the fact that many of the fastest-growing jobs that pay stable middle-class wages are in industries that employ a lot of women, such as health care and professional services.”

That also might help account for the fact that women’s wages have failed to catch up to men’s: Women’s increased presence in caregiving, teaching, and other human services professions has correlated with a decline in the wages of those jobs. According to the New York Times, when women begin to dominate a professional field, wages in that field fall as much as 57 percentage points. Researchers at Cornell concluded “pure discrimination may account for 38 percent of the gender pay gap.” Healthcare and other direct service nonprofits have struggled to pay a living wage, creating “wage ghettos” that disproportionately affect women and women of color. These wage trends affect the entire economy, not just women; last year, NPQ noted that “the United States could add $4.3 trillion to its economy in 2025 if women were to attain full gender equality.”

The decline in men’s wages and the failure of women’s wages to rise proportionately affects more than just their buying power in the market. The Census Bureau study reported that more young men and women live with their parents than with a spouse, and one in four are idle, meaning not working or in school.

As has been exhaustively noted, the much-touted recovery of the economy since 2008 is insufficient, and the recent wage study shows this in stark numbers. For millions of people, wages are not improving, and the need for public service increases even as social programs come onto the federal chopping block. Nonprofits may consider their own roles in this trend, and rethink what might be the most efficient way to provide a decent living for American households.— Erin Rubin