Editors’ note: This piece is from Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine’s summer 2024 issue, “Escaping Corporate Capture.”

In March 2024, I found myself in an extremely contradictory yet familiar position with some of our national partners. Like many others, they had long supported broad declarations for organizing the South and lamented the lack of real momentum in confronting White supremacy and other systems opposed to democracy throughout the region. But also like many others, when presented with a bold strategy that would go beyond minor charitable interventions in one or more small communities or with specific short-term political wins, they were apt to balk.

In this instance, when confronted with the need for an urgent, industrial-level approach centering southern Black workers—given the influx of sustainable energy–based manufacturing to the region, spurred by federal investments—and presented with the proposition of a ragtag group of organizations brought together by the Advancing Black Strategists Initiative to make some initial inroads, they suggested that perhaps we were biting off more than we could chew. It wasn’t the first time I had heard this pushback (or similar variations) of a proposed long-term strategy being “too ambitious” or “someone else’s job.”

As is our way, we blaze on, undeterred—and we will continue to do so until we prove to enough people that the work is worth doing, and build the momentum to succeed. But this last experience got me thinking: maybe it was the nature of the location (the South) and the strategy (explicitly centering the fight against White supremacy and on expanding democracy through a struggle led by workers). And I thought about how much my movement ancestors must have struggled when faced with even harder conversations denouncing their strategies. How many southern Black abolitionists, when campaigning to end forced labor, were told it was just too bold of an idea? How many were told to wait for some better-resourced organization to come and save them? How many formerly enslaved Black workers and their families did Harriet Tubman have to smuggle across the Susquehanna River before those with means started to provide her with support for the next trip?1 And even before such escapes were successful, at what point did anyone realize that the effort alone was worth the money?

Hindsight is indeed 20/20. I realized that what bothered me was how such anxiety-ridden feedback demonstrates a stubborn shortsightedness vis-à-vis the importance of organizing the South. At best, some who organize money still hold a paternalistic view (if unconsciously), seeing it as their duty to provide temporary relief to the long-suffering people of the South when things seem too extreme to bear, such as after a hurricane or a police shooting. The more cynical among them view the region as a lost cause—the heart of the conservative enemy to be bypassed and/or defeated. One funder was blunt in clarifying that the only southern states they would move resources to were Georgia and maybe North Carolina. Maybe. (I guess we’ve lost Florida.) Still others have pet projects in key states but have yet to look at the whole. All these views are narrow, and they are blind to the economic engines of the South and the geopolitical influence they continue to assert.

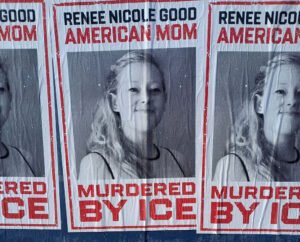

How many southern Black abolitionists, when campaigning to end forced labor, were told it was just too bold of an idea? How many were told to wait for some better resourced organization to come and save them?

However, there are some among us—both in philanthropy and, of course, within base-building organizations directly—who are attempting to focus on the political economy of the region: the industries that have organized and reorganized themselves in ways that have driven economic growth and development throughout the country and the world (mostly unrestricted except for a brief period during Reconstruction), and for whom the structure of government and the politics of those who govern throughout the South have been designed ever since. Because investing in broad-reaching organizing efforts in the US South that emphasize the leadership and economic equality of Black workers against multinational corporations might just launch the nation’s most significant effort yet in the movement to build democracy.

Organizing efforts in the region that emphasize the democratic leadership and economic equality of Black workers and catalyze communities into action would not only lead to victories that would support the people of the South—it would also strike a blow against corporate control and authoritarian rule. This is why we must organize the South: to set the country back on a path toward building a multiracial democracy. To finally win the Civil War.

“How We Win the Civil War”

It’s not as complicated as it may sound. It started with the early rise of the agricultural industry built on chattel slavery, when cotton was king of the exported cash crops—although tobacco, sugarcane, and rice were good business as well. While cotton filled the pockets of the era’s 1 percent, the feeding frenzy was not isolated to the plantation owners in the South: It is well known that national insurance companies—New York Life, AIG, and Aetna—sold policies on enslaved Black workers or allowed plantation owners to put them up as collateral for loans;2 that national banks—parent companies of Bank of America, Wachovia, JPMorgan Chase—funded the expansion of plantation properties;3 that Northeastern clothing companies—Brooks Brothers, for example—relied on cheap cotton from the South and then sold their wares to slave owners as clothing for their enslaved workers;4 and that national food companies—Domino’s Sugar, for one—processed and sold products grown by enslaved Black workers.5 Chattel slavery made a lot of people a lot of money. And not just in the South.

But then there was the Civil War (cue trumpets), and the gravy train ended, right? Not exactly.

Notwithstanding my feelings about Abraham Lincoln and his early eagerness to send formerly enslaved Black people back to Africa before and during the US Civil War, I do think his administration understood the political economy of slavery—and he eventually paid for this understanding with his life. With Lincoln out of the way, the muddier economic interests of the victorious North come into focus. Many have incorrectly suggested—including, most recently, Steve Phillips, in his book How We Win the Civil War6—that Black people were betrayed by their supposed northern political allies in Congress when they began to roll back Reconstruction policy and to yield power to former southern Confederates, as if they had suddenly changed sides. But in fact, the business interests of the Union North had long been fair-weather friends to Reconstruction, being neither universally antiracist nor necessarily opposed to the exploitation of workers (Black or otherwise) for the benefit of the few.7 Envious of the wealth that the southern agricultural industries were able to squeeze from chattel slavery, some industry leaders funding the Union Army had been waiting their turn to exploit Black people—if not as enslaved workers then as undervalued wage laborers. So when the newly reenfranchised southern political establishment found ways to align its interests and allow northern industry access to exploiting southern and Black labor—perhaps masked in a new system of free labor that would seem more humane and digestible to the northern palate, such as prison labor—the allegiances of northern industry shifted. And that’s the political economy we still have in the southern region today.

[N]ow, despite popular misconceptions, some of the most exciting and militant efforts to take on multinational corporations are happening in southern states.

I had a great-grandparent who “did time” laying railroad tracks in Virginia. I grew up in North Carolina, and I remember visiting the Biltmore Estates, a relic of Cornelius Vanderbilt and his post–Civil War railroad empire. How many southerners have ancestors who worked in a coal mine—either in a company town or as a convict laborer? How many of us had a great-uncle who tried to convince us that he knew John Henry while he was leased out to work for one of Andrew Carnegie’s subsidiary companies way back when?

And then of course there’s John D. Rockefeller, the “father” of modern philanthropy. He’s mostly associated with his contributions to the education and health of southern Black people, but within his Standard Oil monopoly, Black and Mexican workers were recruited to live near the environmentally precarious refineries and paid sub-wages to do some of the nation’s dirtiest and most dangerous work.8

As industries shifted and new clashes arose between the old ruling class and the new 1 percent, workers organized. Oil was replaced by textiles, which were then replaced by retail and heavy manufacturing.9 Today, manufacturing is the top industry in the South employing Black men—for Black women, it’s the healthcare industry.10 And new industries are growing at a record speed, including the film industry in Georgia, which is beginning to outpace Hollywood11 and reap big profits for industry leaders at the expense of Black workers in low-wage positions.12 As GeorgiaTrend described it back in 2018, “Y’allywood is No. 1 at the box office. In 2016, Georgia overtook California as the top location for production of feature films—17 of the top 100 grossing movies were filmed here.”13

And now, despite popular misconceptions, some of the most exciting and militant efforts to take on multinational corporations are happening in southern states. The Georgia Film Imperative, a project of ABSI, seeks to create a pipeline for the inclusion and participation of Black and other underrepresented communities in the film industry.14 In September 2023, more than 1,100 workers—the majority of them Black—who manufacture electric buses at Blue Bird outside of Macon, GA, became members of the United Steelworkers (USW).15 In partnership with Jobs to Move America, workers in Anniston, AL, convinced another bus manufacturer, New Flyer, to sign a landmark community benefits agreement, committing to improved wages, training programs, and a reduction in pollution around their facilities.16 In November 2023, 700 call center workers at Maximus, organized with Communications Workers of America, walked off the job, led by Black women in Hattiesburg, MS, and Bogalusa, LA, in response to the company’s silence over issues of basic working conditions.17 In December, southern service workers, backed by SEIU’s United Southern Service Workers, launched drives at major brands like Freddy’s and Waffle House.18 And despite years of setbacks in southern drives, in January 2024, workers organizing with the United Autoworkers surpassed several thresholds to file for election at Volkswagen in Chattanooga, TN, and Mercedes in Tuscaloosa, AL—both with significant Black leadership. In March 2024, a supermajority of VW workers signed cards to support the union in short order, signaling that they would win this time. According to CNBC, they reached their goal in just 100 days;19 and the VW workers won in April 2024.20 While the Mercedes workers lost in Alabama on May 18, 2024, on that same day workers from New Flyer ratified their contract represented by the International Union of Electrical Workers (IUE-CWA), the CWA’s industrial arm—one of two southern electric vehicle plants to unionize within a year.21 All of this comes in addition to workers already in motion from the previous year at Amazon, Starbucks, Apple, and other large multinational brands—including many nationally tracked efforts based in the US South, such as the Memphis 7, who were fired and then reinstated after public outcry.22

This momentum is not new. Southern workers have continuously stuck their necks out for dignity and respect. The difference now for working people in the South is that state governments throughout the region have long acted as an extension of corporate industrial interests, doing union-busting work on their behalf—for free—and acting as a barrier to democratic systems of governance so as to maximize the profits drained from the people of their state.

Why? Because, despite the political repression and culture that have suppressed the rights of workers from all backgrounds, the region’s placement in the country’s political economy still allots southern workers, particularly Black workers, a sort of dormant power that the political leadership of southern states lives in constant fear of (re)activating.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Fast-tracking the construction of a sustainable energy industry represents our era’s best shot at building a multiracial democracy that would sustain the planet and our descendants’ existence on it for ages to come.

In January 2024, South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster named “big labor unions” as a “clear and present danger” to the prosperity of the state when outlining his desires to continue to build up South Carolina as a hotbed of industries that have relocated there in order to escape democracy in action.23 And on April 16, 2024, governors from six southern states released a joint statement opposing the unionization of autoworkers.24 They certainly have reason to be concerned, when so many manufacturers putting in bids for the Biden Administration’s infrastructure investments are abandoning their current union facilities in California (Proterra),25 Wisconsin (OK Defense),26 and even Great Britain (Arrival)27 in hopes of benefiting from a cheaper, Blacker, nonunion workforce in—you guessed it—South Carolina. So while the response of southern state political leaders in Tennessee was late and disorganized, worker–leaders must not underestimate what their opposition will do in what has become the epicenter of the electric vehicle expansion. It will require a well-organized state-, region-, and industrywide response across several unions to curb this new generation of industrial exploitation. And it is to that strategy that we turn next.

The New Industrial Revolution: A Sustainable Energy Industry

As of the last Census, most of the Black population in the United States remains concentrated in the US South.28 Despite political wins in 2020, many movement leaders are divesting from southern states after Republican leaders went to extremes to limit access to political and economic platforms for democracy. During the 2021 legislative sessions, over 440 bills with provisions that restrict voting access were introduced in 49 states, with southern states like Georgia, Florida, and Texas delivering some of the most restrictive provisions via laws, according to the Brennan Center.29 And while state preemption of local laws is not new, its use by Republican state governments as a weapon to whip local democratic cities into compliance has expanded dramatically in the last 10 years. “According to the Local Solutions Support Center, 700 preemption bills were introduced in state legislatures in 2023, virtually all of them by Republicans,” and this is particularly true of the overwhelmingly Republican southern states.30 But those of us paying attention are witnessing a modern industrialization already in motion, driven by the goal to build out infrastructure for sustainable energy production and usage at scale. And along with it, we see a nascent industrial revolution brewing among working people organizing to leverage this new industry in ways that build democracy.

We have a unique opportunity in this moment to align the goals of climate adaptation, economic and industrial democracy, and racial equality.

Fast-tracking the construction of a sustainable energy industry represents our era’s best shot at building a multiracial democracy that would sustain the planet and our descendants’ existence on it for ages to come. Again, manufacturing is the top industry in the South employing Black men, and the trend is only increasing.31 Given the dramatic move of many manufacturers to the US South, successfully incorporating workers, particularly southern workers, into standard setting (even in just one specific section of this new industry: auto manufacturing) would immediately and exponentially increase the number of US-based workers with collective bargaining power—a framework that in itself is a practice of democracy. It would also create a blueprint for industrywide negotiations for this and other sectors, which would pave the way for industrial democracy: a system of industrywide governance (sometimes facilitated by government leaders, though not necessarily), active across competing manufacturers, suppliers, and other key industry stakeholders, in which enforceable standards for the industry as a whole are determined and can be improved upon (but not weakened)via collective bargaining—and through which decision-making is equally and democratically shared among employers and employees.32 Further, given the disproportionate number of Black workers currently operating many facilities there, such an effort would represent the labor movement’s strongest chance to reverse racial inequality—specifically, the hyper-exploitation that southern Black workers have shouldered since the end of the Great Reconstruction and that was later re-enforced during the New Deal era, the New Deal having in many ways been excluded from labor protections.

We have a unique opportunity in this moment to align the goals of climate adaptation, economic and industrial democracy, and racial equality. Of course, there hasn’t been a way to initiate this all at once. But, through their unions, organizations, and regional academic institutions, a group of organizers engaged with the Advancing Black Strategists Initiative have begun organizing Black workers in and around some of the sustainable energy facilities and other sites related to electric vehicle production. The goal is to build an authentic base from which to call on the current administration to facilitate discussions between Black workers and labor and industry leaders across fields.33

Is it almost too big to wrap our minds around? Perhaps. Yet we do not have the luxury not to try.

Steve Phillips was right to argue that the first step to winning a war is knowing you are in one.34 But if that’s the first step, then the second step is to know who you are fighting. “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.”35 Sun Tzu’s famous words can help our metaphorical frontline fighters pull off their blindfolds. While some of us are “inside,” searching for the perfect organization to drive the perfect strategy, we are actually most needed “outside,” leaning into the messy movements in front of us right now, and replacing the rapidly metastasizing antidemocratic practices in the United States with models of democratic decision-making that we can all get behind.

Organizers must challenge the powerful economic forces of the region that impact democracy and economic equality far beyond the Black Belt. When movement leaders design campaigns based in the political economy of the US South, the barriers to democracy come into clear focus.

Setting the Foundation for a Healthy 21st-Century Democracy

There is a reason why unions, in their broadest definition, have often been referred to as “schools of democracy.”36 They are a natural container for working people to come together across race, gender, and other demographics around shared self-interests, and a place to discuss and agitate each other on their values. It’s never been easy; but every generation of the labor movement has transformed its structure and its membership, sometimes in heated internal battles, to meet shared aspirations toward a multiracial democracy. As such, multiracial movements of workers are often the antidote to political forces opposed to democracy. Such anecdotal data have been validated several times over by quantitative analyses showing that a weakening democracy is far more likely when union membership is low.37 As Adam Dean, a scholar on global trade, labor, and political economy, has written, “…in pursuit of open economies, many democracies engaged in brutal repression to crack down on labor union resistance. In the process, they unleashed dynamics that now threaten the survival of democracy itself.”38

Twentieth-century approaches to practicing political and economic democracy never fully made their way to the US South. The Hayes-Tilden Compromise of 1877 that reenfranchised southern Confederates and gave back to them the power of state legislatures completely stunted the forward gains of Reconstruction, including the promise of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery and forced labor, which should have been the foundation of all American labor law. When the New Deal offered yet another opportunity to expand democracy into industry—and later, in the National Labor Relations Act of 1935—to at least ease the pathways to unionization for working people, southern legislators were about to exclude sectors dominated by Black, Mexican, Chinese, and (in some instances) Irish workers (domestic and agricultural labor) from the new labor protections.39 And later, some of the same southern districts went a step further in passing the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which allowed southern state legislatures to, essentially, exclude all workers in their state from federal labor protections, via so-called right-to-work laws.40 Unfortunately, many progressive social movements in the United States fighting against this erosion became too narrowly focused on a rights-based framework, positioning individual rights as the primary framework for issue setting. In doing so, we played into industry’s articulation of us as “special interest groups,” thus making it easier for them to perpetuate exploitative systems.

The good news is, we aren’t starting from scratch. The Advancing Black Strategists Initiative, a partnership between Jobs With Justice, Clark Atlanta University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Southern Center for Studies in Public Policy, and Black strategists across many unions, universities, and organizations around the country, is one of the key strategies emerging from the South that, if successful, could be the difference between a future resilient democracy full of hope that we can all imagine ourselves being a part of and one of the more dystopian realities offered by any number of Netflix series. Having surveyed the landscape, ABSI realized that, by combining resources and efforts to greater nurture the voices, thoughts, and actions of Black labor and economic justice scholars, intellectuals, and other students of social movements, they could help set the foundation for a healthy 21st-century democracy. Its approach is to teach, develop, place, and eventually collaborate with a new generation of Black organizers, lawyers, economists, government officials, journalists, and movement leaders who are aligned with a theory of change that centers the participation of working people in governing all aspects of life. It acts as a container for Black strategists to analyze and learn from the experiences of Black workers and their campaigns, elevate those learnings into public discourse, and apply the lessons learned.41 And by anchoring its program within the historically Black institution of the Atlanta University Center Consortium, ABSI can incubate and grow the scholarship and applied research on race, class, gender, and economic justice in the South as it relates to the grand experiment of building a multiracial democracy in the United States. Partnering with other institutions that are already tackling the great problems of our day, ABSI joins a network of leaders, organizations, and Black-led campaigns on the journey toward innovation, experimentation, and power building throughout the region.

***

Organizers must challenge the powerful economic forces of the region that impact democracy and economic equality far beyond the Black Belt. When movement leaders design campaigns based in the political economy of the US South, the barriers to democracy come into clear focus. And those who invest in broad-reaching southern organizing efforts that emphasize the leadership and economic equality of Black workers against multinational corporations will offer a nation of people who previously turned the other cheek a chance at true redemption—collectively breaking a 400-year cycle of racist exploitation and leading the way for people of all backgrounds to the multiracial democracy our ancestors dreamed of.

Notes

- Because the nature of the underground railroad was stealth by design—the ways were literally written into quilts and songs, with cartographers trying to map it out after the fact—not all the routes have been charted. Harriet Tubman’s most common path was up the Eastern Shore. This is the narrowest section of the Mason-Dixon Line, and the only part that doesn’t really force you to cross the Susquehanna But most paths intersecting the Mason-Dixon Line are difficult to cross without coming into contact with the Susquehanna River. And in fact, we know that some of the more common paths to Philadelphia went across the Mason-Dixon Line right at the point where the Susquehanna directly intersects it (just southwest of Peach Bottom, PA) on their way to Philadelphia through Lancaster/York County, PA. It is here where we have some narratives about Harriet Tubman potentially leading a group there at least once, maybe twice. The narrative comes from a free Black resident who apparently housed Tubman during one of those trips. And reference to the account from the county’s historical society can be found at Scott Mingus, “How Pennsylvania became a safe haven for Harriet Tubman after she escaped slavery in Maryland,” York Daily Record, last modified December 11, 2019, www.ydr.com/in-depth/ news/2019/10/29/harriett-tubman-underground-railroad-path-slavery-escape-pa/3863408002/; and Scott Mingus, “Meet the Underground Railroad conductors who hosted Harriet Tubman in Central Pa.,” York Daily Record, last modified December 11, 2019, www.ydr.com/in-depth/news/2019/10/29/ harriet-tubman-underground-railroad-eliza-ezekiel-baptiste-central-pa/3863180002/.

- See Zoe Thomas, “The hidden links between slavery and Wall Street,” BBC, August 28, 2019, bbc.com/news/business-49476247.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See Steve Phillips, How We Win the Civil War: Securing a Multiracial Democracy and Ending White Supremacy for Good (New York: The New Press, 2022).

- Peter Kolchin, “The Business Press and Reconstruction, 1865–1868,” Journal of Southern History 33, 2 (May 1967): 183–96.

- Kendra Pierre-Louis, “The Fossil Fuel Industry’s Legacy of White Supremacy,” Sierra, April 2, 2021, www.sierraclub.org/sierra/fossil-fuel-industrys-legacy-white-supremacy.

- For a detailed analysis of top industries in each southern state, see “Industries in the South,” Statistical Atlas, accessed May 12, 2024, statisticalatlas.com/region/South/Industries.

- Steven C. Pitts, “The National Black Worker Center Project: Grappling with the Power-Building Imperative,” in No One Size Fits All: Worker Organization, Policy, and Movement in a New Economic Age, ed. Janice Fine et al. (Champaign, IL: Labor And Employment Relations Association, University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, 2018), 115–37.

- Abby Kousouris, “Georgia film space projected to overtake California for top spot,” Atlanta News First, September 13, 2023, atlantanewsfirst.com/2023/09/13/georgia-film-space-projected-overtake-california-top-spot/.

- Per author’s inside

- Kenna Simmons, “GA GA LAND,” Georgia Trend, March 1, 2018, georgiatrend.com/2018/03/01/ga-ga-land/.

- As of the writing of this article, the initiative has not yet been made

- “Workers at Georgia school bus maker Blue Bird vote in favor of United Steelworkers union,” Associated Press, May 15, 2023, apnews.com/article/blue-bird-school-bus-georgia-union-steelworkers-f95e660aabb27abba9b6bd2606fbfc8e.

- Ian Duncan and Spencer S. Hsu, “Labor leaders hail bus maker pact to hire more women, minority workers,” Washington Post, last modified May 26, 2022, washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/05/26/new-flyer-benefits-bus-equity/.

- “Maximus Workers Organizing With CWA Stage Largest Federal Call Center Strike in History,” Communication Workers of America News, November 16, 2023, cwa-union.org/news/maximus-workers-organizing-cwa-stage-largest-federal-call-center-strike-history.

- “Demands on Waffle House: Sign the petition now: Waffle House workers launch a set of powerful demands,” Union of Southern Service Workers, accessed May 12, 2024, org/actions/wafflehouse/. And see Stephanie Luce, “Southern Service Workers Launch a New Union,” Labor Notes, November 22, 2022, labornotes.org/2022/11/southern-service-workers-launch-new-union.

- Michael Wayland, “UAW says VW workers at Tennessee plant file for union election,” CNBC, March 18, 2024, cnbc.com/2024/03/18/uaw-says-vw-workers-at-tennessee-plant-file-for-union-election.html.

- In order to confidently file for an NLRB union election, leaders inside a facility like to know that they have more than just a majority of support, as a company’s campaign will often erode that significantly before workers Workers at the VW plant in Chattanooga thought they’d hit their goals in the past, but they lost each time they attempted to win a union election. Hence, the importance of gaining a supermajority, as happened in this case (and in a similar case in Alabama). See “Volkswagen Workers File for Union Election to Join UAW,” UAW, March 18, 2024, uaw.org/volkswagen-workers-file-for-union-election-to-join-uaw/.

- Josh Eidelson, “Another EV Factory Has Unionized Boosting Labor’s Push In US South,” Bloomberg, May 16, 2024, bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-16/union-wins-at-ev-bus-factory-strengthening-labor-s-us-south-push. (It’s important to note that workers at General Motors’ joint EV ventures in the region were included in the UAW’s national agreement with the company as part of their collective bargaining in fall 2023. See Lindsay Vanhulle, “UAW deal with GM includes nearly $2B in new investment,” Automotive News, November 4, 2023, www.autonews.com/manufacturing/uaw-deal-gm-includes-nearly-2b-investment-future-evs.)

- See Erica Smiley, “The Great Awakening, and Workers’ Fight to Stay Woke,” Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine 30, no. 2 (Summer 2023); Maureen Groppe and John Fritze, “Supreme Court to decide Starbucks appeal over ‘Memphis 7’ fired for trying to unionize,” USA Today, January 12, 2024, www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2024/01/12/supreme-court-starbucks-memphis-7-labor-unions/72207144007/; and Andrea Hsu, “Are workers in the Deep South fed up enough to unionize? We’re about to find out,” NPR, last modified May 11, 2024, opb.org/article/2024/05/11/are-workers-in-the-deep-south-fed-up-enough-to-unionize-we-re-about-to-find-out/.

- “2024 State of the State Address, Governor Henry McMaster,” South Carolina Office of the Governor, January 24, 2024, sc.gov/news/2024-01/2024-state-state-address-governor-henry-mcmaster.

- “Governor Ivey & Other Southern Governors Issue Joint Statement in Opposition to United Auto Workers (UAW)’s Unionization Campaign,” Office of Alabama Governor Kay Ivey, Newsroom Statements, April 16, 2024, alabama.gov/newsroom/2024/04/governor-ivey-other-southern-governors-issue-joint-statement-in-opposition-to-united-auto-workers-uaws-unionization-campaign/.

- Ariana Fine, “Proterra Moves Electric Bus Manufacturing to South Carolina,” NGT News, January 19, 2023, ngtnews.com/proterra-moves-electric-bus-manufacturing-to-south-carolina-facilities.

- Jacob Resneck, “Oshkosh Defense sent a big contract to the non-union Will it keep future jobs in Wisconsin?,” Wisconsin Public Radio, August 9, 2022, www.wpr.org/oshkosh-defense-sent-big-contract-non-union-south-will-it-keep-future-jobs-wisconsin.

- Victoria Tomlinson, “Arrival to build its first S. electric vehicle Microfactory in York County, South Carolina,” Arrival, October 13, 2020, arrival.com/news/arrival-to-build-its-first-us-electric-vehicle-microfactory-in-york-county-south-carolina; and Jay Ramey, “Here’s Why Arrival Will Shift Production To The US,” Autoweek, November 1, 2022, www.autoweek.com/news/green-cars/a41829623/arrival-ev-van-north-carolina-production/.

- “Majority of the S. Black population lives in the South,” Pew Research Center, January 17, 2024, www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/facts-about-the-us-black-population/re_2024-01-18_black-americans_all-black_geography-map-png/; and Mohamad Moslimani et al., “Facts About the U.S. Black Population,” Pew Research Center, January 18, 2024, www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/ facts-about-the-us-black-population/.

- “Voting Laws Roundup: December 2021,” Brennan Center for Justice, last modified January 12, 2022, brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-december-2021.

- Harold Meyerson, “Pre-preemption,” American Prospect, February 6, 2024, prospect.org/politics/2024-02-06-pre-preemption/.

- Pitts, “The National Black Worker Center ”

- Definition of “industrial democracy” is the author’s. It is also important to make the distinction here between industrial bargaining and sectoral bargaining. While subtle, and perhaps used interchangeably by many, a sector is more general and can represent various fields of work in the economy: the service sector; the healthcare sector; the fast-food sector; the entertainment Industry, on the other hand, typically references manufacturing, or the production sector. Both sectoral bargaining and industrial bargaining cut across employers, as do others (bargaining with the 1 percent, supply chain bargaining, global brand bargaining, bargaining across migration corridors). But industrial bargaining is unique and more significant in that if you consider a Gramscian theory of political economy—that societies have a fundamental base economy capped with a political structure, topped off with a hegemonically reenforcing (cultural) superstructure—and if you thus understand the strongest part of that economic base to be what a society “produces” (or in late-stage finance capitalism, how a society might benefit from production), then bargaining in an industrial setting (i.e., in the production sector) has implications for society (economics, politics, and culture) far beyond simply the wages and conditions of workers in that sector. So, incorporating democratic governance in the sector of production (i.e., industrial democracy) would significantly improve conditions for expanding multiracial democracy overall.

- See Advancing Black Strategists Initiative (Washington, DC: Jobs With Justice Education Fund, 2022).

- Phillips, How We Win the Civil War.

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Lionel Giles (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2002), 51.

- For a detailed study, read Clayton Sinyai, Schools of Democracy: A Political History of the American Labor Movement (Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 2006).

- Asha Banerjee et , “Unions are not only good for workers, they’re good for communities and for democracy,” Economic Policy Institute, December 15, 2021, www.epi.org/publication/unions-and-well-being/.

- Adam Dean, “How Free Trade Threatens Global Democracy,” LPE Blog, The Law and Political Economy Project, March 28, 2023, lpeproject.org/blog/how-free-trade-threatens-global-democracy/; and Adam Dean, Opening Up by Cracking Down: Labor Repression and Trade Liberalization in Democratic Developing Countries (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

- For further study on the unique exclusions, struggles, and victories of Black and Irish domestic workers during this era, the author suggests reading Danielle T. Phillips-Cunningham, Putting Their Hands on Race: Irish Immigrant and Southern Black Domestic Workers (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020). Likewise, there are many books that describe various controlled immigration programs of Mexican and Chinese workers for the purposes of agricultural work, rail work, and work in other sectors, along with the racism and xenophobia these workers endured. See David W. Galenson, review of This Bittersweet Soil: The Chinese in California Agriculture, 1860–1910, by Sucheng Chan, Journal of Economic History 47, 4 (December 1987): 1051–52; and Erasmo Gamboa, Mexican Labor & World War II: Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942–1947 (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2000).

- The labor policy of the Reconstruction era is arguably the most powerful still in effect today: the 13th Amendment to the United States However, it is rarely evoked as an anchor to modern labor law due to what many southern leaders saw/see as the defeat of Reconstruction in the US South. Most scholars refer to the end of the Reconstruction era with the Compromise of 1877. In How We Win the Civil War (cited earlier), Steve Phillips elaborates on this framework by describing the Hayes-Tilden Compromise of 1877, by which, in exchange for conceding the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes, southern Confederate leaders regained control of their state apparatus, and federal troops were withdrawn. Phillips wrote, “The result, as Lerone Bennett Jr. wrote, was the ‘funeral of democracy’” (p. 46). A similar compromise was made during the New Deal Era, this time with the so-called Dixiecrats representing the southern states in Congress. In his definitive book on the period, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright, 2013), Ira Katznelson wrote that the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 amended the historic National Labor Relations Act of 1935 when it “authorized states to pass ‘right to work’ laws.” He noted, “By the early 1950s, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia had passed such laws, effectively bringing labor organization to a halt” (p. 394).

- See “Advancing Black Strategists Initiative,” Jobs With Justice, accessed May 13, 2024, jwj.org/our-work/absi.