The Form 990 is not simply a boring tax document you’re required to file. The Internal Revenue Service barely looks at it; in fact, the IRS has been auditing only about 1.3 percent of nonprofits each year, though this may change with the Service’s new approach to regulating exempt organizations. The 990’s true audience is rating agencies, individual donors, institutional funders, and journalists. We know what they are looking for—overhead—and we also know where they look: Part IX, Statement of Functional Expenses.

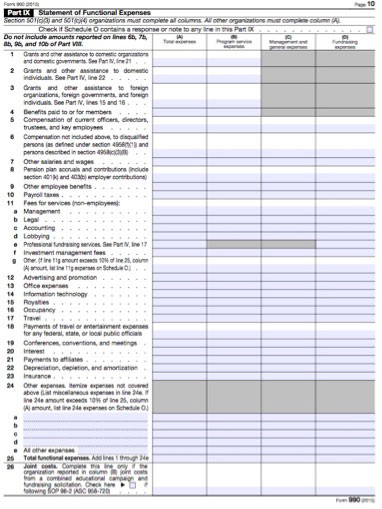

If anything kicks off the Nonprofit Starvation Cycle, it’s this part. Part IX crudely asks you to report how you spent your money in up to 26 buckets against three categories: program-related expenses, management and general expenses, and fundraising. When nonprofit organizations start to fudge these numbers, they give the false impression that they don’t need adequately funded administration and fundraising operations. This is how the cycle starts: a façade of light overhead on a legal document to impress potential donors that makes it harder and harder to justify funding the nonprofit’s business and fundraising operations.

If Part IX is both Ground Zero for nonprofit starvation and the primary source lazy journalists use to take down nonprofits, let’s fix the problem at its source: Let’s rewrite Part IX. For example, Line 17 of Part IX is “Travel.” What does this line really say about your organization? Imagine how easy it would be to misinterpret. A much better and more informative line would be “Professional Development.” It’s an expense line in which an organization should take pride. Yes, it is “overhead,” but it’s an investment in the organization’s staff to make them stronger. A smart donor would look at that line and expect it to be significant.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Part IX’s Line 11 has several sub-lines that seek to tease out what kind of professional services you have outsourced and what kind of consultative services you have paid for: Management, Legal, Accounting, Lobbying, Professional Fundraising Services, Investment Management Fees, and Other. None of these lines inform the reader if you have spent money on strategic planning, program development, capacity building, or board development—all things that nonprofits absolutely need to spend money on from time to time.

If we want to break the nonprofit starvation cycle, we have to fix the source of the problem. We have to redesign the 990 in a way that induces nonprofit organizations to be honest and open, leaving the 990’s true audience better able to see how much of an organization’s functional expenses are not mere overhead but how the organization invests revenue internally to become stronger and grow its outcomes.

Some sites, like GuideStar and others, allow nonprofits to insert more carefully fashioned explanations of their budgets into their public profiles in order to tell their full stories and fill in the unnecessary ambiguities that the 990 fosters. This can help the nonprofit justify what is happening on its 990, but it also opens the door to misrepresentation. It’s critical that the IRS Form 990, the one document for which the nonprofit is held accountable, provides a critical but fair platform for organizations to explain their business practices to society.