November 9, 2020; WBUR

As the number of coronavirus cases globally surpasses 50.4 million, with over 10 million in the US alone, this week brought some good news on the vaccine front. Pfizer, which has been developing a vaccine in partnership with BioNTech—though, explicitly, not part of the government-backed Warp Speed program—announced that its Phase 3 clinical trial shows 90 percent efficacy, a much higher positive result than many expected. Nonetheless, public health experts and epidemiologists continue to warn that these are preliminary findings, too early to be definitive and not yet reviewed by independent scientists.

The good news is that among the 94 vaccine trial participants who contracted the virus, 90 percent, or about 85, received the placebo, suggesting that the vaccine does prevent infections. But there are multiple questions still to answer:

- Does the vaccine prevent severe disease? If the vaccine can prevent the worst outcomes from COVID-19, it could reduce the strain on our hospitals and future healthcare needs. But as yet, the trial has not identified participants who have become seriously ill and analyzed the efficacy of the vaccine in that group.

- Does the vaccine work across all groups, particularly people with disabilities and people who are elderly? Many vaccines are not effective in older people, whose immune systems become weaker as they age. The trials do not necessarily include sufficient numbers of people who are older than 65 or have comorbidities such as diabetes to determine if these people, who are most vulnerable to severe COVID-19, will be protected by the vaccine.

- Does the vaccine produce immunity that lasts more than a few weeks or months? The clinical trial data demonstrates that the vaccine was effective in the first few weeks following the second dose of the vaccine. But will it still be effective in six months? We don’t know.

This last point is particularly important. The rush to bring a vaccine to market could backfire if people think they are protected and don’t take standard precautions such as using masks and remaining socially distant.

Dr. Marc Hellerstein, a vaccine researcher and toxicologist at the University of California, Berkeley, explained to NPR that the Pfizer vaccine, as well as all similar vaccines in Phase 3 trials, focuses on producing antibodies, and much depends on how long these antibodies live.

“This is what scares me—say you give some people a vaccine, and it just gets antibodies. A year later, they’re dying away because that’s how long these antibodies live. Six months, even less,” Hellerstein says. Once the antibodies fade, it’s not clear if the body will necessarily mount a strong defense.

Hellerstein suggests that a vaccine targeting T cells, a type of white blood cell that helps fight infection, could provide immunity for a much longer period, possibly indefinitely. People who recover from mild cases of COVID-19 have few antibodies but more T cells—and that’s the process we want to mimic, notes Hellerstein.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

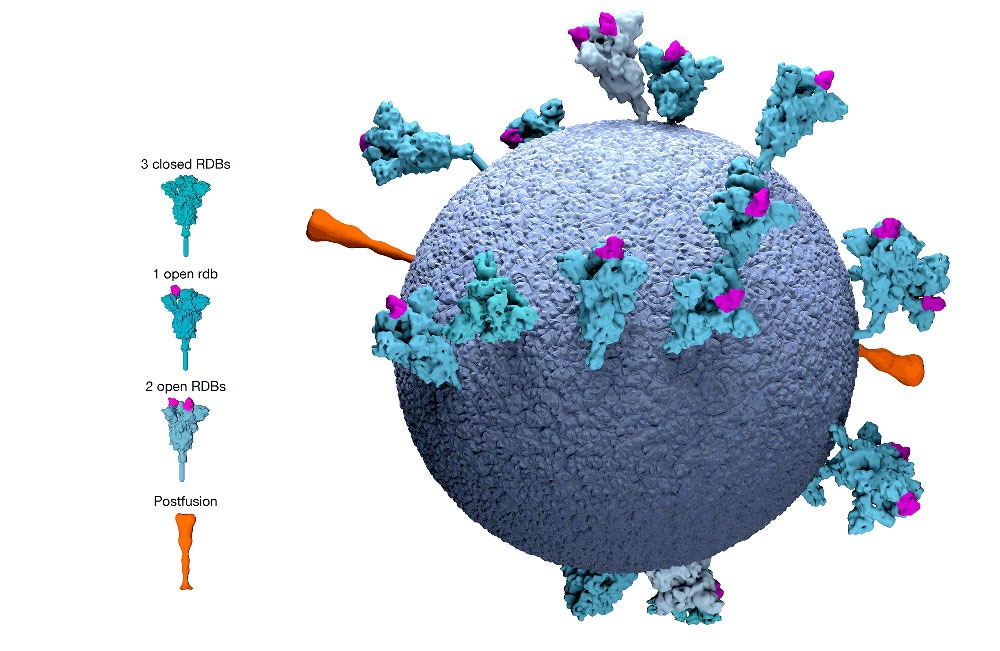

People with the virus produce many different T cells, targeting different parts of the coronavirus. The current vaccine candidates, however, all produce a T cell that targets just one part of the virus, what is known as the “spike protein.”

Says Dr. Anne De Groot, the cofounder of the vaccine development firm EpiVax, “I would say it’s five different flavors of vanilla.”

If it turns out the spike protein target doesn’t work, that will set back the vaccine effort by years. De Groot tells NPR we “need a plan B,” in which we develop vaccines that focus on different targets, in case the first approach fails.

Pfizer plans to ask for Emergency Authorization Use of its vaccine in the US by the end of this month. At that point, the firm will have completed the trial period the FDA has set for determining safety. If approved, the Trump administration has agreed to pay Pfizer nearly $1.95 billion to begin production of 100 million doses for the US Pfizer says it can produce as many as 50 million doses by the end of the year, and can make 1.3 billion available globally in 2021.

The question, of course, is how these will be distributed, and to whom. Among the many challenges are two that are particularly concerning to public health experts. First, the vaccine must be stored at very cold temperatures that are difficult to maintain. This will make it far more difficult to get the vaccine to rural communities around the globe, and to distribute it through places like community health centers and pharmacies that have become the go-to locations for vaccinations for millions of Americans without easy access to a primary care physician.

Second, those people who are vaccinated will have to return to get a second dose about three weeks after the first dose, complicating the process, particularly if more vaccines come on the market. It will be important for individuals who get the vaccine to get a second dose of the original vaccine they were given. This will require flawless record-keeping—something that remains elusive in the privatized, fragmented US healthcare system.

How this all happens is now up to President-elect Joe Biden, who announced on November 9th an expert panel to lead his coronavirus response. After nearly a year of failed leadership, we can expect more coherent messaging and greater attention to the details of vaccine efficacy and distribution. We should also expect to continue our current strategy of masks and social distancing throughout 2021.—Karen Kahn